We Can All Join In: How Rock Festivals Helped Change America

by Bill Mankin – Mar 4, 2012

The dawning age of America’s great rock festivals was legendary both for its music and its massive crowds. But a different kind of legacy could be its greatest.

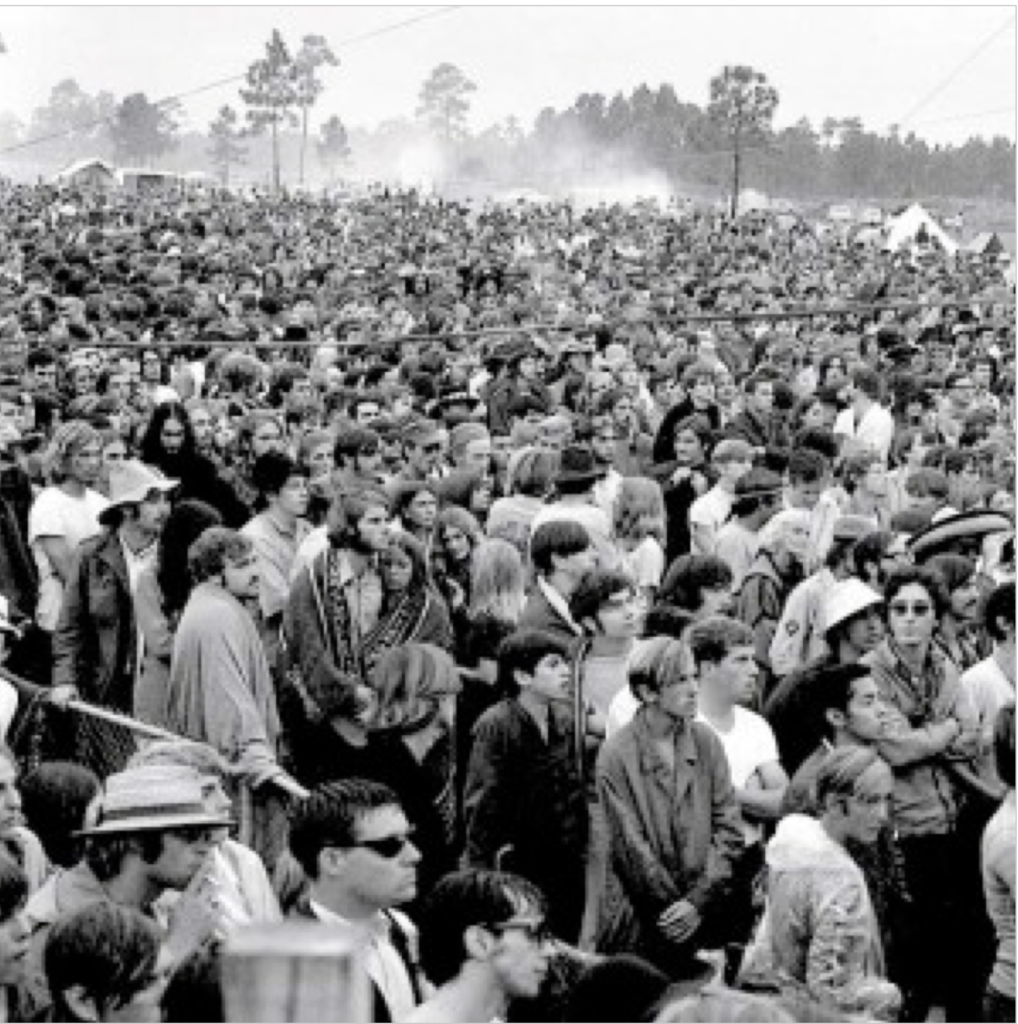

Crowd huddled against the cold at the Palm Beach Pop Festival, November 1969.

Photo © Bob Davidoff / oldrockphoto.com.

When the Rolling Stones took to the stage one windy November night in Palm Beach, Florida, in 1969, it’s doubtful their audience had any thoughts of politics or cultural change. We were just a crowd at a rock festival who had endured a downpour the previous day and now braved the bone-chilling cold front that had rolled through. It was hours after midnight and we had waited a long time for this moment. We were simply die-hard music fans, huddled together, buzzed and ready to rock. And rock we did. As dawn later broke and we began to drag ourselves back down the highways to our ordinary lives, we gave no thought to whether we were taking anything with us besides all that magnificent music ringing in our ears. Nor did we wonder if we were leaving anything in our wake besides our footprints in the mud. Now, upon reflection…

For the last several decades it has been argued that, in the 1960s – or, more accurately, the period roughly between 1963 and 1975 – a cultural revolution[1] of historic importance took place in America. Although the scale of its significance can be debated, it is indisputable that, during those years, some of the most deeply-rooted pillars of America’s staid social structure of the time were shaken, and either rearranged, removed or rebuilt. In any case, the status quo was irrevocably altered and a ‘counter culture’ began to emerge.

As this disruption and renovation occurred, it involved events that were sometimes thrilling, sometimes frightening, and very often unsettling to one group or another. It proceeded on many fronts at the same time and embraced a wide spectrum of social issues. These included the struggles for civil rights and women’s liberation; the sexual revolution; environmentalism; protests against the Vietnam war, the draft and nuclear weapons; countless skirmishes for greater freedom of speech and self-expression, including fashion and personal appearance; the emergence of new and experimental art forms and cinema, and an avalanche of new music; the search for alternative routes to spiritual enlightenment; experimentation with mind-altering drugs and entirely new lifestyles; and the beginnings of the gay rights movement.

This was not a single, organized, or even coherent effort at societal reform, but a chaotic jumble of mostly unconnected streams, often with very different constituencies who, like blacks and whites, lived in different worlds and had different priorities. Though all were moving in the same general direction, they tended to move at their own rates. Some, like the civil rights movement, which had begun in the 1950s and was a prominent forerunner of change, took the form of deliberate, hard-fought political campaigns. Others were more in the nature of socio-cultural trends, and were diffuse and spontaneous. Taken together, however, they represented a tidal wave of change that swept across the country, leaving little familiar ground for anyone – young or old, black or white – to stand on. Ultimately, to one extent or another, all sectors of society were affected. Many people believe this wave forever altered the way most Americans saw, and later generations would see themselves, their nation, and the world.

As different as some of these transformative upsurges were from each other, most of them had a lot in common. By and large, whether politically shrewd, stubbornly idealistic or naively anarchic, they were based on the expectation that the world could – and should – be a better place. Most were driven or fed by a hunger, and then a clamor for greater individual rights, freedoms and choices; for greater social tolerance of personal differences; and for better opportunities for all. In one way or another, they all necessitated transgressing boundaries, breaking down barriers, skewering sacred cows, and opposing societal norms that had been in place for a very long time. Finally, if any of these shifts were to take hold, they also required on the part of individuals the personal courage to think for oneself; to question and doubt; to challenge conventional ‘establishment’ views and entrenched authorities; and, if necessary, to ruffle feathers and break social taboos.

The initial spark for each of these concurrent countercultural upheavals was struck by a relatively small number of courageous leaders or creative innovators, and was fanned into flame by similarly small numbers of early-adopters. Of course, in the early-to-mid-sixties, much of America was none of the above. Except for a few vibrant nodes of activity in New York and California, and perhaps a few other big cities – and for several focal points of the civil rights struggle – the rest of America was largely unaware, disinterested, or ignorant.

As soon as the news began to leak out, however, many of the country’s relatively innocent views shifted rather dramatically. For most of adult America, all these unsettling cultural awakenings suddenly became things to be questioned, to be skeptical of, scoffed at, rejected, feared, condemned, opposed, suppressed, or prohibited by law. But the counterculture would be propelled by the young, so it was their views that mattered most. Yet a lot of the country’s young baby-boomers were just beginning to become more conscious and curious teenagers and young adults. They were intrigued by all the new sights, sounds and fashions, and were simply eager to learn more. But for most of them, especially in the face of often disapproving parents and teachers, figuring out how was quite a challenge.

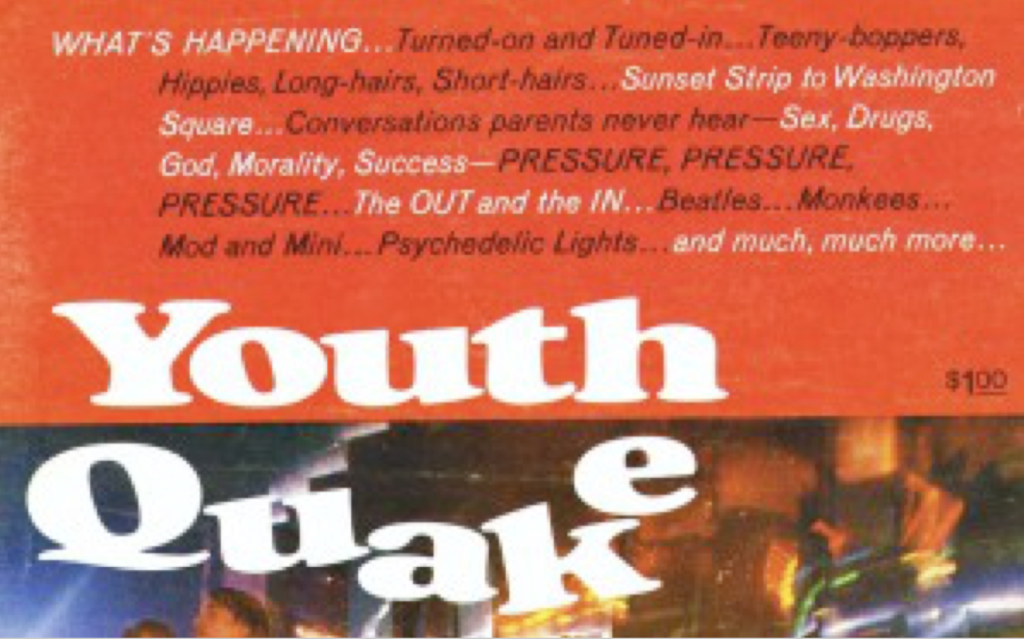

From the cover of Look magazine’s special issue.

From the mid-sixties onward, the news and entertainment media began to feature more and more stories and programs describing the most visible, eye-and-ear-catching parts of the counterculture’s leading edge. Many of these representations were often just bemused sidebars and filler material, or sensationalized accounts focusing on the most radical departures-from-the-norm: particularly zany, picturesque, or shocking individuals or events. In 1967, Look magazine took a more in-depth approach by publishing a special issue titled “Youth Quake”, which asked, “What’s the younger generation coming to?” Many of that generation’s seemingly wilder behaviors were given close scrutiny. For the most part, Look attributed them to either typical youthful exuberance and rebellion, to passing fads, or to a small minority of radicals or oddballs, and confidently pronounced the bulk of America to still be a “vast stretch of common sense” – unafflicted by the ‘quake’. Yet at some point it was no longer possible to ignore that something more substantive was going on, and that somewhere out there, interesting things were beginning to happen and a new world was, in fact, unfolding.

Slowly but surely, awareness began to spread. Even so, the most readily available information sources still painted only hazy, two-dimensional, and usually quite sanitized fragments of the whole. And for most young Americans, ‘out there’ seemed very far away indeed. Even for the insatiably curious and adventurous, finding some place to directly encounter the counterculture in concrete form – in-the-flesh – was still extremely difficult. Unless they could jump in a car and hit the road for New York, San Francisco or Los Angeles (beyond contemplation for most), they were pretty much stuck in a sea of post-war convention and conformity and racial separation. For a lot of America’s youth, it might as well have still been the 1950s, especially if they lived at home with mom and dad.

So where could young people go if they wanted to explore this new world and find a tangible sample of what the counterculture was offering, if only to learn more about it, to try to make sense of it, or to see if they might like it? If they lived in a region like the South, this challenge was considerable, but in Atlanta, if they were daring enough, they could at least venture in to the early midtown coalescence of hip shops, clubs and cafes that would come to be called The Strip. To call it a coalescence, though, would have been generous, because the individual hip locations were often several blocks apart and fairly nondescript – more like isolated outposts. Nevertheless, with a little effort, intrepid explorers could wander from one to the other and at least see some of the emerging culture’s trappings: posters, clothes, incense, jewelry, beads & leather goods, rolling papers and other drug paraphernalia, underground newspapers like Atlanta’s own Great Speckled Bird, poetry readings, and folk or rock music performances.

Middle Earth Head Shop on 8th St. in Atlanta, ca. 1968.

Photo © Robert L.E. “Arlo” Forbes, Jr.

One Atlanta shop, Middle Earth, was my favorite. They had a whole room full of day-glo posters bathed in the dark indigo-blue of several ultraviolet ‘black lights’. Every time I visited the shop I would spend a long time in that little room, my nostrils filled with the heady incense that always burned, gazing at those glowing other-worldly poster-worlds covering the walls and ceiling.

In those early days, those who populated Atlanta’s actual counterculture probably consisted of no more than a few hundred people scattered pretty widely through midtown and other somewhat solitary spots. As a result, visitors could walk for blocks and blocks and never see anyone who looked remotely ‘counter’ to anything, much less even slightly ‘cultural’ in any way. If they were lucky, they might see someone with really long hair, or even more impressive, someone who appeared to be living an authentic ‘alternative lifestyle’ – a real hippie. More likely, though, they’d see a few others like themselves, merely visitors who, at the end of the day, would head back to wherever they’d come from in the midst of the dominant, non-counter culture, typically (for whites at least) the suburbs. Nevertheless, curious young visitors would try to make the most of every visit and every encounter – probably assuming, or fantasizing, that such things were more than they really were.

Atlanta youth displays the archetypal greeting and hopeful gesture of the day.

Photo © Carter Tomassi.

I remember having read something in the newspaper about a midtown Atlanta diner that apparently had become an early hippie hangout, and it was generating some controversy. So one Saturday morning I went down to see for myself – and hopefully to rub shoulders with the counterculture. I walked into the diner with anticipation, expecting to immediately see what all the fuss was about, but the place looked ‘normal’, and boring, with not a single hippie in sight. I sat at the counter, ordered a piece of pie, ate it… and waited. Finally, I gave up and left, sorely disappointed that I’d wasted my time and not found the Holy Grail I’d sought. I decided to walk around for a few blocks to see if ‘it’ might be happening somewhere else, but, like the diner, normality was still abroad in the land. Then, as I walked up one side of the street I noticed a guy with very long hair walking down the street on the other side (my own hair was nowhere near the length of his, but it was still longer than the typical denizen of Atlanta in those days). As we drew near to our opposite points across from each other, we both broke out into huge smiles, nodded our heads in recognition, and flashed each other the two-finger ‘V’ peace-sign. We were complete strangers, yet we felt an immediate and solid rapport between us, as though we were members of a secret society – all based on our outward appearance.

A somewhat richer opportunity for sampling and interacting with the counterculture was offered by another midtown feature, Piedmont Park, which began to attract real crowds of like-minded people – hippies and would-be hippies who congregated for free weekend performances by local, Atlanta-area rock bands on makeshift stages, or no stage at all. The significance of such gatherings was that they would attract several hundred people, giving visitors, samplers and observers of all kinds a growing sense of comfort and belonging, a chance to mix with each other, and a little bit more courage to dress and act however they pleased. The sensation of strength-in-numbers could be exhilarating. For individuals from far-flung high schools who otherwise felt like – or were treated like – they were weirdoes, freaks or outcasts, it was a relief to have a place where they could let their guards down and ‘do their own thing’. Authority figures were few and far between, and incense and pot smoke wafted on the breeze to enhance the sensory experience and give things an extra edge of rebellion.

Typically, the curious visitor to these gatherings would find that some musician or garage band they knew from their own high school was performing, and they’d inevitably see a few of their friends in the crowd. So the experience wasn’t so much an encounter with the counterculture as communing with their similarly inclined friends – all looking for the counterculture but largely unaware that at the very same time they were, in fact, creating one of the counterculture’s spontaneous and increasingly numerous local flowerings. Also, because these were usually just long afternoons, it was rare in the early days for anyone from another town elsewhere in the state to travel into Atlanta to join in. So, while participants may have occasionally been thrilled by their growing local numbers, they rarely got the impression that they were more than a hometown phenomenon, and they had little sense they were part of a nationwide movement. At the end of the day they’d all pile into their cars and return to their own neighborhoods, and on Monday they’d be back at school or work.

Free music in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park exploded in the late 1960s.

Photo © Carter Tomassi.

Atlanta had some exceptionally talented bands at that time. One of the best, most original, and most avant-garde, was the Hampton Grease Band, who played a lot of free gigs in Piedmont Park. So we were used to hearing great music on those sunny afternoons. But one day will always stand out in my memory. As one band played in a nearby pavilion, a white van pulled up to another one of the park’s improvised stages – a set of stone steps with a broad patio in the middle. A bunch of longhairs no one had seen before began unloading and setting up musical gear on the patio. This was only mildly interesting until they set up the second of two drum kits; this got everyone’s attention. When the other band had finished playing, these new guys turned on their amps, did a quick tune-up, and then hit us with the most breathtaking blues-rock performance most of us had ever heard. They announced they were from Macon, Georgia, and called themselves the Allman Brothers. Soon, they were famous.

The ‘draw’ for those gatherings in the park was always music. From the beginning, music – especially the newest and most groundbreaking music – was the most fluid, subversive and powerfully influential catalyst helping the counterculture to spread and coalesce. It alone seemed to have the power to act as a common, galvanizing thread, weaving together disparate individuals, groups, interests and intentions. It was still a considerable challenge for new music to break through the tight barriers of Top-40 AM radio ‘pop charts’, and hip young listeners who craved a broader sonic spectrum often had to search hard for what they wanted. Nevertheless, the commercial drive to sell more products to the large baby-boomer generation eventually convinced even conservative businesses and radio programmers to provide young Americans with more opportunities to hear and buy at least some new music. Progressive and ‘underground’ FM radio stations (often on college campuses), record stores with younger staffs, and adventurous local cover bands helped to fill in the still-considerable gaps.

Crowd at the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival – the world’s first known rock festival, June 10-11, 1967.

Photo © Bryan Costales.

The new music, often full of countercultural messages, became something to rally around for growing numbers of adherents, who admired and idolized the musicians who created it. Fans anxiously awaited new record releases with their often artistically-adventurous album covers, which frequently displayed vivid images of outrageous new modes of dress and personal appearance. Still, it was quite a while before more than a few of the most innovative and rebellious of these musical pioneers managed to tour the country and make it into the average American town or city to perform live. When they did come to town, their shows were still relatively fleeting encounters that lasted only a few hours, and concert-goers went back home to sleep in their suburban beds once again – already eager for the next concert.

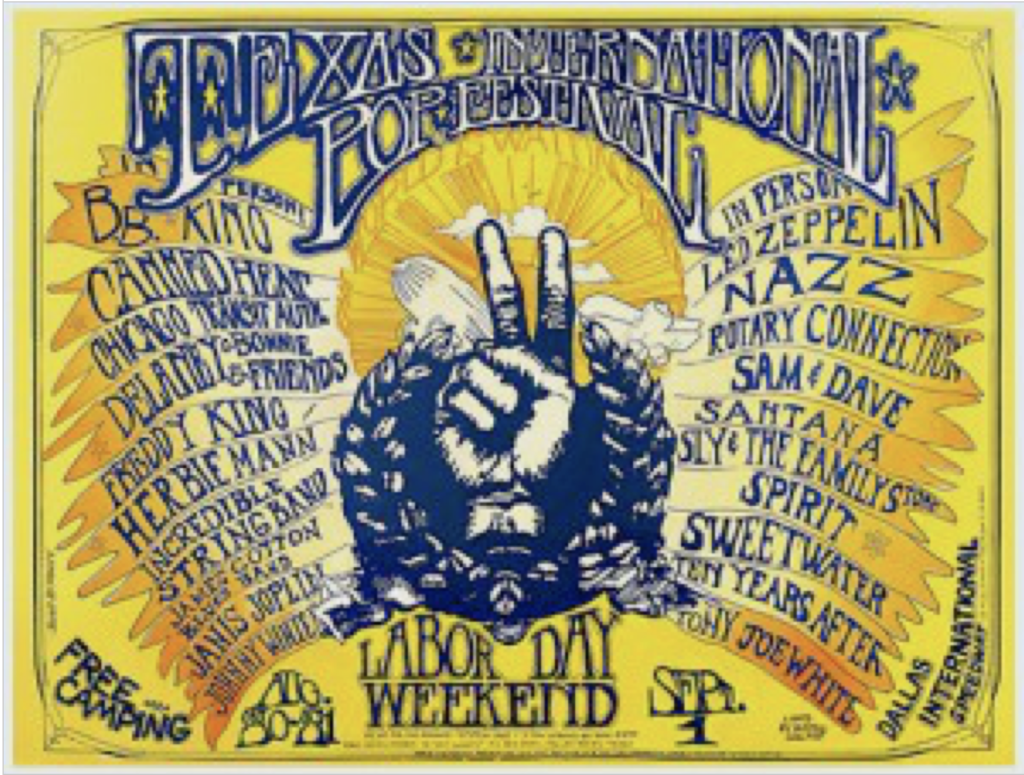

In 1967, while all these and other events were occurring, a new musical marvel, and a far more lively and intense opportunity for personal countercultural immersion, came into being – the rock festival. That was the year when, on two back-to-back summer weekends in northern California, the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival and theMonterey International Pop Festival took place. These outdoor extravaganzas gave crowds of music lovers and would-be (and actual) hippies several days in a row in which to commune both with each other and with an impressive line-up of the superstars and soon-to-be superstars of the new, fast-evolving musical universe. The concept proved irresistible.

Posters with impressive lists of scheduled performers were a magnet for would-be festival-goers. The basic, now iconic, design on this one (by Lance Bragg) was used on posters for three different rock festivals in 1969 and 1970.

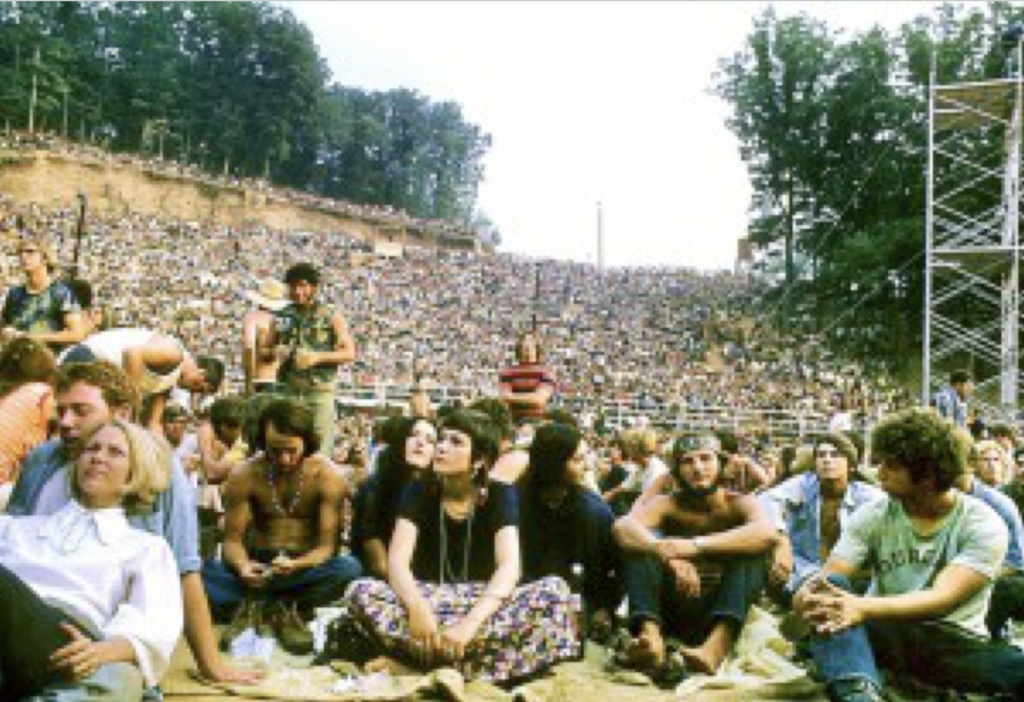

Within two years the multi-day outdoor rock festival had spread across the country, giving vastly larger numbers of Americans a chance to venture much more deeply into the heart of the counterculture itself, and to personally sample some of the trappings and elixirs it had to offer. In those early years, each festival was unique, dynamic and experimental, and they evolved fast. A few rose to mythic status after films documenting their wonders appeared in theaters nationwide, rapidly swelling the ranks of would-be festival-goers looking for the next festival, and inspiring new entrepreneurs to stage even more of them. In one form or another (depending on how the term “rock festival” is defined), dozens of these events occurred in America between 1967 and the mid-1970s. California hosted as many as ten, Florida six, and Georgia held two, with the second in 1970 drawing several hundred thousand music-lovers to a rural soybean field in the central part of the state. By the end of that year, over two million young Americans had already had a personal rock festival experience.

Most revelatory for festival-goers – no doubt in large part because of the sheer size of the crowds – was the sudden sense that the counterculture was big, and because people often came from great distances, it was geographically diverse and interconnected. Furthermore, it had a lifespan of far more than a few hours; it was comprised of fully mobile leaders and innovators (i.e., the rock stars, most of whom were only slightly older than their audiences); and – most importantly – it was wide open and welcoming to all comers. Audience members could feel that they, themselves, were actually part of it. They were making it happen just as much as anyone else. They now held one of the brushes and were helping to paint the countercultural canvas.

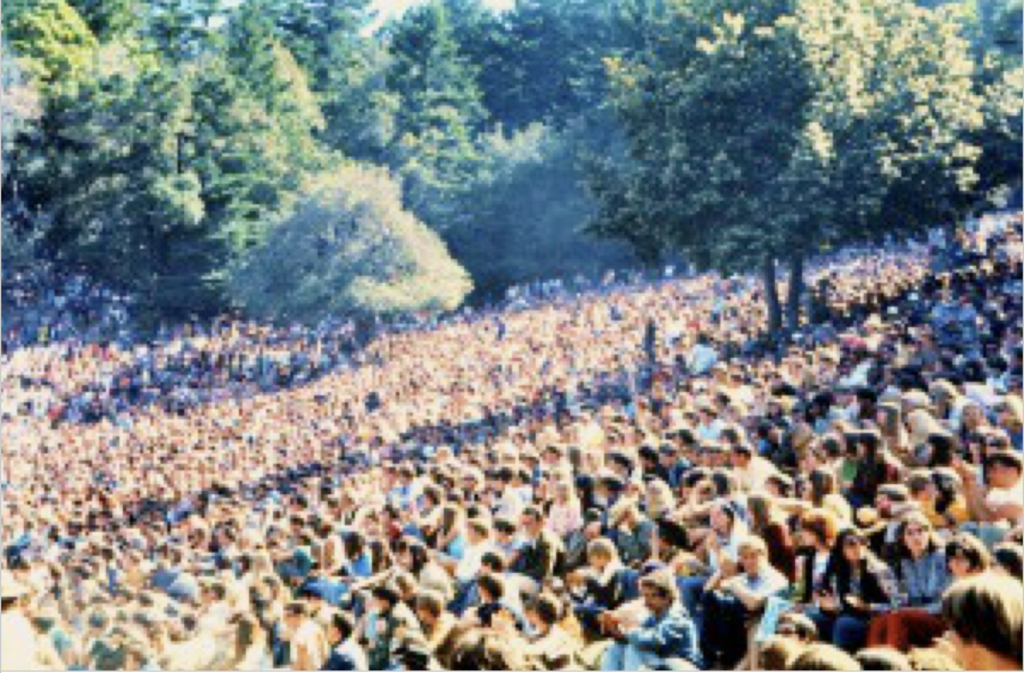

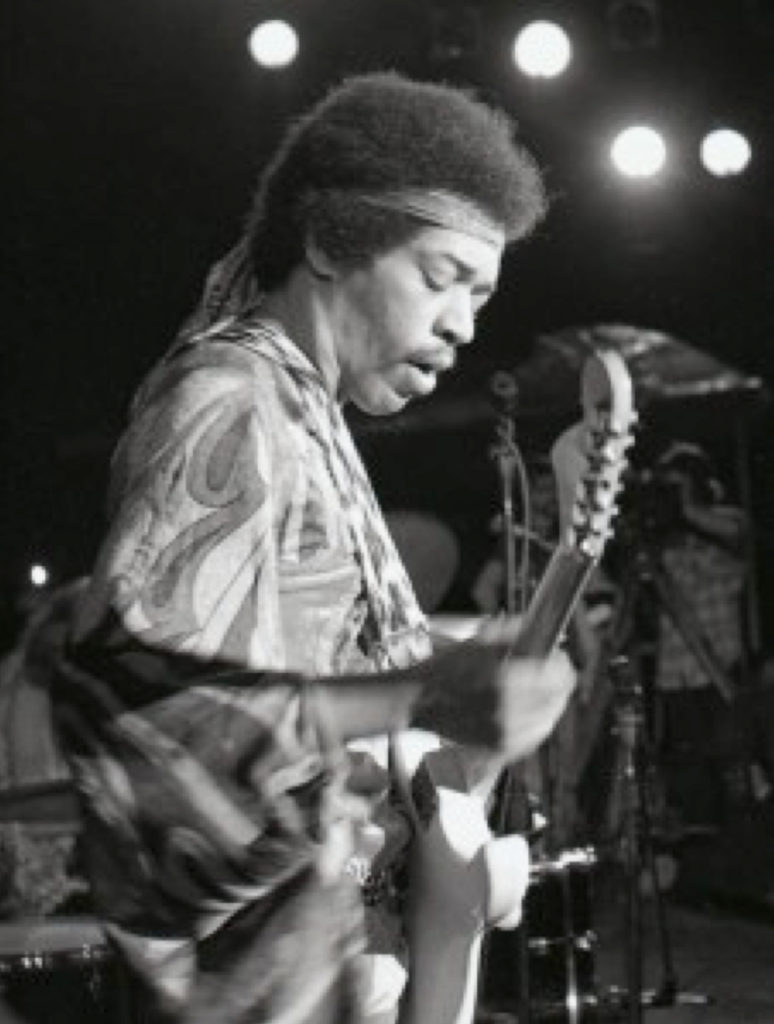

My first rock festival was in December, 1968, in Hallandale, Florida, just north of Miami. As with all the festivals I attended, I went for the music. There they were, all these bands I had been hearing on FM radio: Procol Harum, Iron Butterfly, Canned Heat, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the original Fleetwood Mac, and many more. Obviously my full attention was focused on these avatars of the counterculture as they played, one after the other, all day long for three full days. At the same time, however, I could not fail to notice that some of the people scattered around me in the audience seemed to be just as far out in their appearance and behavior as those on stage. I began to realize that it was not just a courageous vanguard of artists and musicians, but seemingly ‘real’ people who were adopting hippie ways – even as far away from California and New York as southern Florida. I attended my second festival the following summer in Atlanta, where I got to see Led Zeppelin and Janis Joplin, among others. I was stunned by the size of the crowd. By the summer of 1970, the audience at the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival in middle Georgia was truly immense, and the crowd that heard Jimi Hendrix was full of people who looked and acted very different than they had just a year or two earlier. Clearly something amazing was happening – and happening fast.

The second Atlanta Pop Festival in July 1970 drew one of the largest rock festival audiences anywhere during the Sixties era.

Photo from panoramic composite © Earl McGehee.

At a rock festival, young people were completely on their own, unfettered, away from parents and, most of the time, away from public authorities. Significantly, they were usually there for several full days and nights. They could eat, sleep, dance and sing any time they wanted. At most festivals, those who were so inclined could more or less freely engage in drinking and drug use, take off their clothes, and even have sex (in a sleeping bag, a tent, the bushes, even with a complete stranger) – all in the company of a huge crowd – in effect, in public. But it was a ‘public’ that was riding the same wild river they were: everyone in sight was part of a collective consciousness, experiencing and sharing a new and exciting world at exactly the same moment, in sync to the same exuberant rock’n’roll beat. For a few days at least, a rock festival could feel like another planet, where the rules of ‘normal’ society simply did not apply. It was a cornucopia of artistic and personal expression and experimentation that permitted each individual to dramatically accelerate their personal countercultural learning-curve with a single, concentrated dose.

For those who were relative virgins to such things, a rock festival could provide them with an initiation or a jump-start. If they’d already learned a thing or two elsewhere, a rock festival could broaden and intensify their awareness and experience, or let them push their own boundaries a bit further. One thing about rock festivals: because each attendee was surrounded by such a large crowd, so many of whom seemed to be ‘doing it’ (no matter what ‘it’ was), whatever personal inhibitions they may have had when they arrived tended to loosen up pretty quickly. But whether or not they were inclined to personally sample the various exotic fruits on offer, or to engage in any extreme or risky behaviors themselves, they could readily observe others who did, giving them an even broader set of experiences and benchmarks by which to re-examine or redesign their own life if they were so disposed. For many young people, in the midst of their most impressionable and formative years, a rock festival could represent a significant rite-of-passage. Some found they could leap from relative innocence to full immersion in a single weekend.

From left: Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann and Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead, at the Miami Pop Festival, December 1968.

Photo © Bill Mankin.

Not long after The Grateful Dead hit their first note at the Miami Rock Festival in December 1969, people in the audience near the stage began turning around and passing things to those behind them. Eventually, these little gifts reached me: tiny blue tablets. Then the word spread through the crowd that they were LSD, and that they somehow came from the band – a band that openly extolled the wonders of this psychedelic drug and supposedly did what it could to turn-on its audiences as often as possible. I did my part and politely passed these offerings along. Later that same day I took a real fancy to a girl who was sitting near me. At some point I asked her what her name was and we spent that night together inside my sleeping bag, oblivious by then to the music and the people around us. After the festival, we never saw each other again.

Whether or not anyone decided to personally embrace any of these behaviors as components of a new ‘lifestyle’, at least now they knew a lot more about them, if not what they tasted like on their own tongue. They now knew firsthand that hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of other young Americans were experimenting with, creating and sharing this same rich tapestry of freedoms, delights and debaucheries right along with them. The possibilities – with all their attendant social and moral questions and challenges – began to approach the limitless, and nothing stood in the way of anyone’s partaking. There was almost nowhere else than at a rock festival where it felt like one could tap so deeply and directly into the communal coronary artery of the counterculture. It was truly heady stuff. At the same time, because it was generally an easy-going, non-confrontational environment where audience members were surrounded by a bunch of people just like themselves, without an apparent care in the world, sharing everything they had with each other, most of them had a whole lot of fun.

On the surface, rock festivals might have appeared to be rather narrowly about sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, and perhaps fad and fashion – to fleeting, self-indulgent excess – rather than about the weightier social and political concerns of the time. Also, many festival-goers no doubt attended rock festivals as an escape-valve, to get away from generational rifts, family frictions, and the worries of the wider world. Furthermore, for a number of reasons (the nature of the times, differing musical preferences, targeted radio playlists and stations, among others) rock festival audiences were predominantly white. Thus it might seem that if such festivals had any meaningful socio-cultural impact at all, it was probably negligible and of little long-lasting consequence. But such an impression would be far too simplistic.

From left: August Burns, Fred Herrera, Nancy Nevins and Albert Moore of Sweetwater, performing at the Miami Pop Festival, December 1968.

Photo © Bill Mankin.

While festival audiences may have been drawn by the lure of their favorite bands, they were invariably also exposed to bands they had never heard before and would never have had a chance to see or hear in any other context. Rock festivals often featured a diversity of music genres and performers, and the sights and sounds they presented shouted out loudly that the times were definitely changing. For example, the mere sight of some of these bands sent a powerful message that ethnic diversity was cool and racial harmony was not only possible but on the horizon: The Allman Brothers Band had a black drummer, while the otherwise all-black Chambers Brothers had a white drummer; the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Sly and the Family Stone, and Booker T. & the MGs were in the vanguard as racially well-integrated bands; Indian Ravi Shankar, South African Hugh Masekela, Puerto Rican José Feliciano, and Canadian Cree Buffy Sainte-Marie all graced festival stages; Jimi Hendrix, of mixed black/Native American heritage, became a rock music icon fronting a band with a white drummer and a white bass player; and the bands Santana and Sweetwater displayed a level of multi-ethnic diversity well beyond mere black and white. As for the role of women: Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick, Ten Wheel Drive’s Genya Ravan, and Tina Turner, among others, showed festival audiences that women could be more than sweet soul singers and pretty-voiced folk singers, and much more than girlfriends or groupies – they could rock as hard and front a band with as much command as any man.

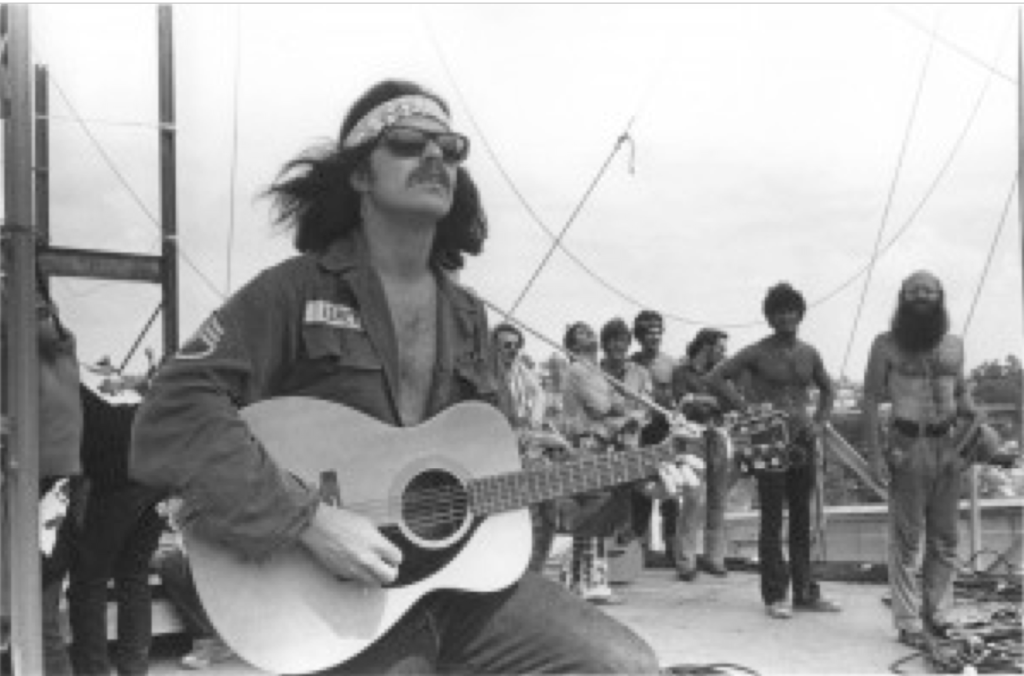

Country Joe McDonald surveys his half-million-voice chorus at Woodstock, August 16, 1969.

Photo (courtesy of Joe McDonald) © Jim Marshall.

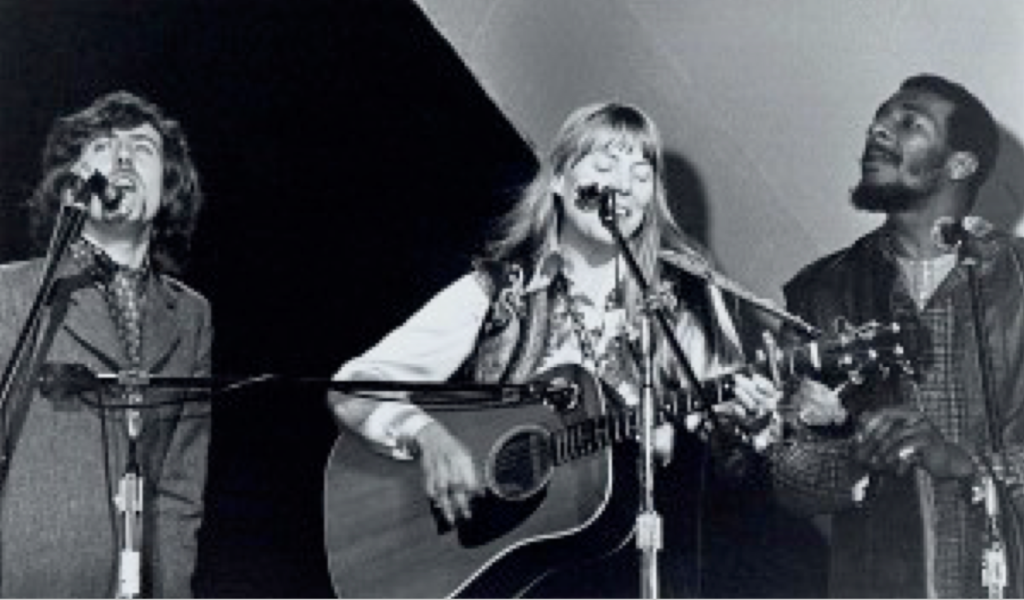

Richie Havens (right) joins Graham Nash for an encore with Joni Mitchell at the Miami Pop Festival, December 1968.

Photo © Bill Mankin.

It is also important to remember that many of the social/protest movements of The Sixties embraced singer-songwriters and incorporated their music to instill solidarity and help convey their movements’ core political messages. Even artists not directly associated with such movements wrote songs reflecting the turmoil of the times. So it should not be surprising that the songs some artists brought with them to rock festival stages contained provocative and politically-charged lyrics. As The Sixties progressed, song lyrics rapidly evolved from containing the occasional subtle or veiled political reference to include much more candid, direct, and in-your-face refrains.

At Monterey Pop in 1967, most of the featured bands sang songs full of love and angst and other familiar teenage concerns, with a few indirect drug references thrown in. Yet there were some notable departures from this mold, including Laura Nyro singing “Poverty Train”; Buffalo Springfield describing “battle lines being drawn [and] a thousand people in the street, singing songs and carrying signs” in their hit song “For What It’s Worth”; and Country Joe & the Fish doing their not-subtle-at-all, anti-Vietnam War “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag”, and their very short but to-the-point “The Bomb Song”.

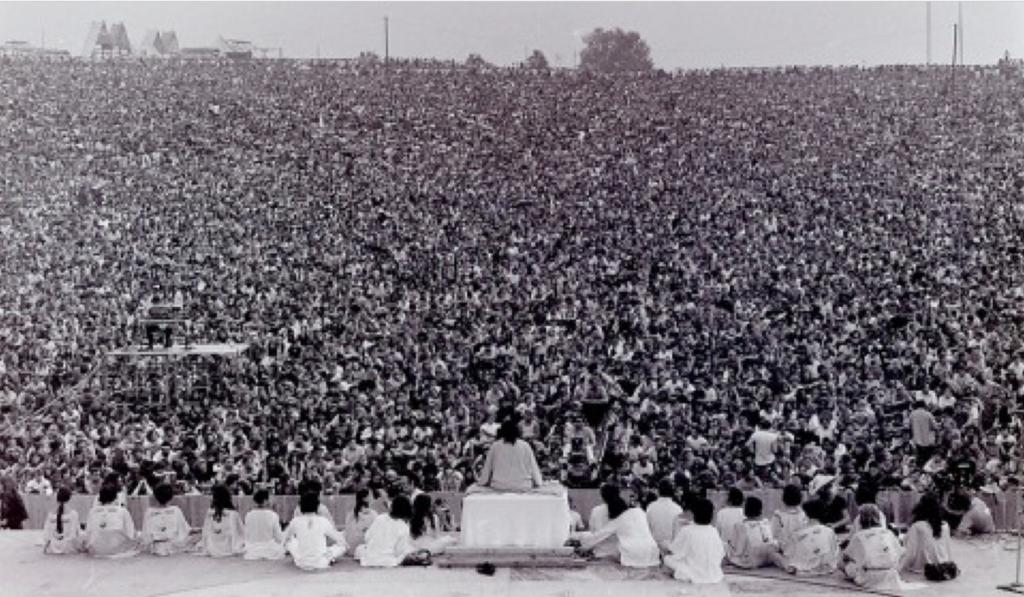

Political messages also featured on the stage at the famed Woodstock festival two years later, where at its peak the crowd out front may have been seventy times larger than Monterey’s. Richie Havens sang of “Handsome Johnny with his hand rolled in a fist, marching to the Birmingham war”; Tim Hardin presented his “Simple Song of Freedom”; Joan Baez sang a song about labor organizer Joe Hill, as well as the civil rights rallying-hymn “We Shall Overcome”; Jefferson Airplane exhorted the audience to “Look what’s happening out in the streets – got a revolution” in “Volunteers”; Country Joe McDonald turned his “Fixin’-to-Die Rag” into a soon-to-be-infamous sing-along with the entire crowd; and Jimi Hendrix recast the “Star Spangled Banner” as a psychedelic anthem-for-electric-guitar for a new generation, seeming to proclaim: ‘this is our country now, and we’ll define it on our own terms’.

Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of his career at the 2nd Atlanta Pop Festival, July 4, 1970.

Photo © “craZy jiM wGGns”

As the focal point of every festival, it was the music that carried everything along and cemented it all together. In another context, such as a concert hall, this music may have been labeled as mere entertainment, but at a rock festival everything seemed magnified. For example, based on a single festival performance, numerous bands and individual artists were given significant career-boosts, and some were catapulted into musical superstardom, leading audiences to expect unforgettable events to take place on festival stages. More than this, however, when charismatic performers and their music were presented in the context of a multi-day rock festival with a sizable roster of bands, they produced a one-of-a-kind alchemy that fused three exceptional powers: the potential to attract extremely large crowds – perhaps the single most potent ingredient in the mix; the persuasive ability to convey things to those crowds (attitudes, behaviors, fashions, political messages – and emotional fervor); and the capacity to meld those once-assembled into a more socially aware multitude that felt like they were part of a broader movement – a new social order, fired-up and full of hope. Not surprisingly, the synergistic effects of all this on a festival audience were often exhilarating and tended to last well beyond the festival itself.

Despite their ability to inspire, the impressions left on audiences by message-laden song lyrics and multi-racial bands were not the strongest transformative forces at work at a rock festival. Nor were the occasional overtly-political statements made from festival stages; the presentation of some festivals as charitable events to benefit worthy causes; the camaraderie that developed among crowds of strangers who collectively endured occasional harsh weather and shortages of a full range of basic necessities; or the many volunteer efforts and countless acts of kindness to help provide food, water, medical care, and rides home to those in need. These things were clearly important, and they all added up, but there was still something more going on.

In fact, it was the assembled masses themselves, and the unexpected synergy of it all, that created something much more far-reaching and embracing of everything the counterculture represented. The contagious sense of personal freedom, disintegrating boundaries, freewheeling rebellion, and boundless horizons that permeated such huge gatherings had extraordinary power and momentum, and created an enduring impression on those in attendance. Long after the seemingly superficial, ephemeral, and hedonistic aspects of the event itself had faded, many festival-goers found they were beginning to see the wider world – including their home towns, high schools and college campuses – and their own lives, very differently than they ever had before. Somewhere along the way, these people had become the counterculture.

Once someone had been to a rock festival, they often felt like they had been initiated into a very special tribe – exclusive yet enormous, and growing. Every time they subsequently heard the music of any of those festival-playing bands – whether on the radio, on records, or at another concert – it was like hearing the tribal yell. They didn’t even need to embrace any particular countercultural behavior or live any particular ‘lifestyle’; now that they knew they had the freedom, they had the license. They could be anyone they wanted to be. They felt empowered and emboldened, and their eyes, ears – and minds – were open. They could engage in any version of this brave new world they chose, at any pace they desired, or (more likely for many) to any incremental degree their parents, teachers or employers would permit. Once they’d been ‘anointed’ by a rock festival they carried its spirit, and the promise of an almost limitless world of countercultural possibilities, with them – inside – from that point forward.

Rock festivals brought their indefinable wonders to some unlikely places, such as Love Valley, NC, where this sizable crowd attended the Love Valley Rock Festival in July 1970.

Photo © Ed Buzzell.

Although rock festivals lacked most basic creature comforts and were often physically draining to attend (mostly due to sleep deprivation), I never wanted them to end. As the crowds began to leave and the euphoria to fade, I would sometimes linger and wander through the empty grounds, stepping through several days’ worth of audience debris and lost or discarded clothing, simply savoring the last vestiges of the magic and wishing it would live on – or perhaps trying to find something solid and material that could represent all the indefinable wonders of the event itself. No matter. To one extent or another I still carry all those wonders with me today.

If the essence of the counterculture from the mid 1960s through the early 1970s was a hungry fire-in-the-belly for greater rights, freedoms and opportunities, rock festivals spread a lot of fuel across the American landscape. In one way or another, each festival lit a fire of some kind and left its mark as a cultural change-agent. Each one planted a milepost on the road between one American era and all those that came afterwards – and an indelible memory in the mind of every attendee. Whether it was new music, art and fashion; political outrage and rebellion; a desire for peace, brotherly love and racial equality; psychic or spiritual enlightenment; or simply expanding personal horizons – rock festivals sprinkled fertile seeds of change far and wide. In the process, and purely by chance, they turned legions of festival-goers into potential emissaries of a new kind of culture, a new way of being – like free-floating spores scattered on the wind.

It may be difficult to accurately measure their lasting cultural significance, but it is surprising how many people who attended one or more such festivals will, when asked, express not only fond memories but some version of “It changed my life”. Similar sentiments are often expressed by those who attended rock festivals during the same period in Europe and Canada; and in Latin America, where such festivals were inspired by those in the US, although they were fewer in number, these events were usually much more daring, rebellious, and influential culturally – and politically. Moreover, millions of young people who never made it to a single festival heard all about them from their friends, from media coverage, and from films about them. Many of these people were affected by the stories they heard and wished they had been there, and some began seeking what they had missed, changing their own lives in the process.

Certainly there were other events, developments and gatherings that had a major socio-cultural and political impact during those years, which arguably comprised one of the most dramatic and volatile periods of cultural evolution in American history. Be-ins, sit-ins, teach-ins, protests, demonstrations, rallies, marches, and the collective student bodies of college and university campuses nationwide – all played their parts as communal opportunities for personal participation in the transformation. But perhaps it would not be an exaggeration to say that, over a few short years, rock festivals played a unique, significant – and underappreciated – role in fueling the countercultural shift that swept not only America but many other countries, over forty years ago. It seems fitting, then, that one of the most enduring labels for the entire generation of that era was derived from a rock festival: the “Woodstock Generation”.

Opening ceremony welcomes historic throng to the Woodstock Music & Art Fair, August 15, 1969.

Photo by Mark Goff (public domain).

POSTSCRIPT

By the mid-1970s, the heyday of rock festivals was over, or so it seemed to a lot of people at the time. Several factors conspired to this end. First, even from the beginning some festivals were plagued by problems, including poor planning, legal battles, inadequate facilities and services, protests over ticket prices, immobilizing traffic jams, crowds too large for the venues, gate-crashers, financial shortfalls, and skirmishes outside the events between over-exuberant and unruly festival-goers and local police. Next, due to the unmanageable flood of people who showed up at Woodstock – overwhelming the ticket booths and fences – its promoters had declared on the first day of the festival that it was thereafter “a free concert”. From the extensive media coverage and the popular Woodstock film, many rock festival fans around the country got the message, were inspired, and demanded free entry at subsequent festivals, routinely breaking down fences to get in.

Then, in December 1969, at a huge, one-day free festival in Altamont, California, a gun-wielding audience member was stabbed to death near the stage during an altercation with members of the Hells Angels motorcycle club. This sad event (again widely publicized by the media and a film) spread dark clouds over the whole idea of festivals and scared plenty of state and county government officials nationwide. Increasingly fearful of drugs, violence, and Woodstock-sized throngs, they enacted new laws and ordinances severely restricting or prohibiting such events, following in the wake of similar ordinances that had been multiplying around the country in response to previous problem-ridden festivals. It became harder and harder, and much more costly, for festival promoters to stage them.

These and other developments sent rock festivals into a long spiral of decline, and a long period of uneasy evolution, and their numbers dropped off considerably for years – but they did not die, mainly because, despite their flaws and risks, rock fans still wanted them. The cultural revolution of The Sixties – with its accompanying explosion of rock festivals – had made its mark during a relatively brief moment of history, and as the decades passed, the times, and the world, continued to change. So did large outdoor music festivals, which not only survived but had a resurgence, flourished, multiplied and diversified (and became more commercial). There are now several hundred that take place all over the world every year, featuring an incredibly wide range of musical genres. Their role in society may now be different, but these festivals are still significant cultural events that attract millions of fans.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the pivotal role of rock festival promoters, who courageously took on the challenging task of staging these massive, logistically complex, often controversial, and financially risky events. Some, like the following, were both visionaries and trailblazers: Tom Rounds and Mel Lawrence, who produced the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival on California’s Mount Tamalpais in June 1967 – the world’s first known rock festival –as well as the second Miami Pop Festival in December 1968; Alan Pariser, whose original concept became the Monterey Pop Festival, and Derek Taylor, John Phillips and Lou Adler who joined in (with others) to make it happen; Michael Lang (who produced the first Miami Pop Festival in May 1968) and Artie Kornfeld, who together produced Woodstock in 1969; and Atlanta’s Alex Cooley, who organized two festivals in Georgia, one in Texas, and one in Puerto Rico between 1969 and 1972.

[1] Prior to the flood of cultural changes ushered in by the era now called ‘The Sixties’ (roughly 1963-1975), the scene had been set during the previous two decades by, among other things: the end of, and America’s victory in, World War II; the dawn of the age of nuclear weapons, and America’s use of them in Japan; the beginnings of the US-USSR Cold War, nuclear arms race, and Space Race, and the promotion of an East vs. West, Communist vs. Capitalist world view; the emergence of a massive American ‘military-industrial complex’; the stalemate and armistice ending the Korean War; growing American military involvement in Vietnam; the beginnings of the civil rights movement; a huge surge in the number of births (the ‘baby boom’), the entering of all those young people into their teenage and college years, and the rise of a ‘youth culture’; a new level of economic affluence, which spawned a surge in materialism and consumerism; rising numbers of both college graduates and career expectations; the construction of vast stretches of a new national interstate highway system, the greater mobility it conferred, and the further expansion of a ‘car culture’; the mushrooming of suburbs on the periphery of urban cores; the expansion of broadcast radio and TV into a ‘mass media’, and the resultant creation and spread of a popular or ‘mass culture’ with all its implications of sameness and conformity; the ‘training’ of Americans by mass commercial advertising to be attracted to the latest/newest thing; a uniquely American form of post-war optimism that held that the country, and particularly young Americans, could attain any goal they set their minds to; the development and subsequent government approval of a birth-control pill; the invention and early-stage mass-prescription by doctors of mind-altering drugs for the treatment of depression and anxiety; and the advent of rock’n’roll. In addition, several pivotal events of the early 1960s shook the nation resoundingly out of its relative comfort and complacency: the hair-trigger nuclear standoff of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 ignited fear; the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 brought grief; a rapid succession of significant civil rights events shattered long-standing social conventions and began to break the back of over three hundred years of racial subjugation and discrimination; and the formal involvement of America in the Vietnam War, which led to the compulsory drafting of large numbers of young men into the military to fuel the war, began to divide the nation against itself.

Many of the cultural changes that occurred during The Sixties were triggered by disillusionment or disenchantment with, and then a rejection of things that had become the ‘norm’, such as rampant materialism, and ‘traditional’ values, gender roles and measures of success. Others were sparked by resentment and rage, and involved direct opposition to longstanding social injustices and oppression, or to horrible governmental misadventures like the Vietnam War and its draft. Still others evolved from a combination of the fear, anger and fatigue many felt from the perpetually confrontational, ‘us vs. them’ Cold War deadlock of international politics and American foreign policy. Some simply grew from boredom, restlessness, curiosity, and a desire for excitement and liberation from repression and social strictures. Some of the efforts to create change opened the door, set the stage, or paved the way for others; many moved at different rates; and some faded away while others are still going strong. Soon enough, a growing number of shifts and changes began to occur, to gain momentum, and to add up to something historic. Taken together, the people and their efforts and struggles, the changes themselves, and sometimes even the entire era are often referred to as ‘the counterculture’. Another way of looking at The Sixties is to recall the familiar quote: “It was not just a decade; it was a state of mind.” – full of rebellion, excitement, idealism, hope, and a desire to make the world a better place.

© 2011, 2012 William E. Mankin.

###

All photos are copyrighted by their respective owners (unless otherwise noted) and are used with their permission. All rights are reserved. Unauthorized use is prohibited. Photo Credits: Crowd huddled against the cold at the Palm Beach Pop Festival, November 1969. Photo ©Bob Davidoff / oldrockphoto.com. Middle Earth Head Shop on Eighth Street in Atlanta, ca. 1968. Photo ©Robert L.E. “Arlo” Forbes, Jr.Atlanta youth displays the archetypal greeting and hopeful gesture of the day. Photo ©Carter Tomassi. Free music in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park exploded in the late 1960s. Photo ©Carter Tomassi. Crowd at the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival – the world’s first known rock festival, June 10-11, 1967. Photo ©Bryan Costales. The second Atlanta Pop Festival in July 1970 drew one of the largest rock festival audiences anywhere during the Sixties era. Photo from panoramic composite ©Earl McGehee. Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann and Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead, performing at the Miami Pop Festival in December 1968. Photo © Bill Mankin. August Burns, Fred Herrera, Nancy Nevins and Albert Moore of Sweetwater, performing at the Miami Pop Festival, December 1968. Photo © Bill Mankin. Country Joe McDonald surveys his half-million-voice chorus at Woodstock, August 16, 1969. Photo (courtesy ofJoe McDonald) ©Jim Marshall. Richie Havens joins Graham Nash and Joni Mitchell for an impromptu medley at the Miami Pop Festival, December 1968. Photo © Bill Mankin. Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of his career at the second Atlanta Pop Festival, July 4, 1970. Photo © “craZy jiM wGGns”. Rock festivals brought their indefinable wonders to some unlikely places, such as Love Valley, North Carolina, where this sizable crowd attended the Love Valley Rock Festival in July 1970. Photo ©Ed Buzzell. Opening ceremony welcomes historic throng to the Woodstock Music & Art Fair, August 15, 1969. Photo by Mark Goff (public domain).

AboutBill Mankin

Bill Mankin first fell in love with music listening to late 50s radio in a small suburban town north of Chicago. That love blossomed and then exploded in Atlanta in the 1960s, and then got interesting: from 1968-1973 Bill attended five rock festivals in Georgia and Florida (two of which he worked for), and worked on innumerable rock concert stage and security crews, in promotions, as a stage manager, and on concert tours as an equipment roadie, truck driver, and sound technician in charge of stage audio. Via the great good fortune of world travel as an international environmental activist, Bill’s musical tastes have significantly broadened over the years, and he is just as likely to fall in love with a new artist from Mali as he is to wax nostalgic over an old psychedelic San Francisco favorite. In 1980 Bill won a Bronze Award from the Houston International Film Festival for his screenplay about dreams and desperation in the world of rock’n’roll. He also wrote the liner notes for the Jimi Hendrix album release, “Freedom.” He is currently researching and interviewing for a book about the December 1968 Miami Pop Festival. In his spare time, he occasionally recalls a favorite Leonard Cohen quote from Chelsea Hotel No. 2: “We are ugly, but we have the music.”