GSB, Mar 20, 1975 Vol. 8 #12 pg. 9 “Printing the news you’re not suppose to know….”

Seven years ago the first issue of The Great Speckled Bird hit the streets of Atlanta-March 8, 1968. A history of the BIRD since then would inevitably include the rise and fall of the “hippie” era in Atlanta. The BIRD did not create the Atlanta hippie scene, nor did the latter create the BIRD. Yet, they struggled against some of the same powers, hand-in-hand. At the same time they often were in conflict with each other-politics vs. lifestyle.

Seven years ago the first issue of The Great Speckled Bird hit the streets of Atlanta-March 8, 1968. A history of the BIRD since then would inevitably include the rise and fall of the “hippie” era in Atlanta. The BIRD did not create the Atlanta hippie scene, nor did the latter create the BIRD. Yet, they struggled against some of the same powers, hand-in-hand. At the same time they often were in conflict with each other-politics vs. lifestyle.

-courtesy Bill Mankin.

The forerunner of the BIRD was an anti-Vietnam War weekly newsletter on the campus of Emory University in 1967, the Emory Herald-Tribune. A decision to go to a larger format created the Big American Review. At that time the movement for social change was almost non-existent in the South. Joining the Emory radicals were political activists from the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC), VISTA, and other organizations.

The high-energy level of the people involved kept the idea alive and, in fact, expanded the concept from a campus-wide publication to a city-wide underground newspaper. By this time there was a burgeoning movement of organizers in Atlanta.

Weeks of meetings and arguments failed to produce a curable name. Atlanta Cooperative News Project was the only name that everyone at least did not disagree about for the publication. It would have remained at that, but one night some of the people involved with the fledgling newspaper heard Rev. Pearly Brown sing an old Roy Acuff song. “The Great-Speckled Bird” is a spiritual known by blacks and whites, and is strictly Southern. Basis for the song comes from a Bible verse, “Mine heritage is unto me as a speckled bird, the birds round about ire against her; come ye, assemble all the beasts of the field, come to devour.” (Jeremiah, 12, 9)

From the beginning the name was unusual, catchy, and held a significance. The description in the Bible verse also came to hold true to the newspaper, which found itself hassled and harassed by the FBI, city government, Atlanta Police Department and the business community starting with issue one. The reasons given for these harassments were assorted cosmetic charges: “panhandling,” “obscenity,” “obstructing traffic,” “selling without a permit,” “inciting to riot.” In every instance a BIRD-related matter was taken to court, the newspaper was found to be in the right. First Amendment advocates note that governmental efforts to close down the BIRD by forcing it to cease publication arose out of discomfort—a newspaper had finally arisen in Atlanta, “printing the news you weren’t supposed to know.”

From the beginning the name was unusual, catchy, and held a significance. The description in the Bible verse also came to hold true to the newspaper, which found itself hassled and harassed by the FBI, city government, Atlanta Police Department and the business community starting with issue one. The reasons given for these harassments were assorted cosmetic charges: “panhandling,” “obscenity,” “obstructing traffic,” “selling without a permit,” “inciting to riot.” In every instance a BIRD-related matter was taken to court, the newspaper was found to be in the right. First Amendment advocates note that governmental efforts to close down the BIRD by forcing it to cease publication arose out of discomfort—a newspaper had finally arisen in Atlanta, “printing the news you weren’t supposed to know.”

That first issue cost $130 (1968 dollars) to put out. Everyone who had helped put it out hit the streets in the evening to hawk this new paper to Atlantans. Much to their surprise and delight the 15 cents collected for each copy sold amounted to enough money to print the next issue. The Great Speckled Bird was a success, or a curiosity-piece, or something but it caught attention.

Later, as harassment plagued the BIRD, the national news media picked up the story and helped spread the name. Nationally, people at first considered the BIRD an anomaly-this radical voice coming out of Atlanta, Georgia, of all places. As people involved in the movement throughout the nation became acquainted with the BIRD, its reputation grew, based on its editorial content. This editorial content was also what got the BIRD in trouble with Atlanta’s government and business communities.

Over the years the BIRD has reflected the subject concerns of the individuals working on the paper, but in an intended collective fashion. The underlying thread has been action for social change; the specific ideologies have ranged along the left-end of the political spectrum, somewhere beyond liberal. The BIRD has gone through many phases, depending upon the people putting the most energy into the paper. The first issue concentrated on draft resistance, anti-war activities, civil rights concerns, and the student and GI movements. These interests have continued to be included in the BIRD’S coverage with emphasis going to other areas at different points.

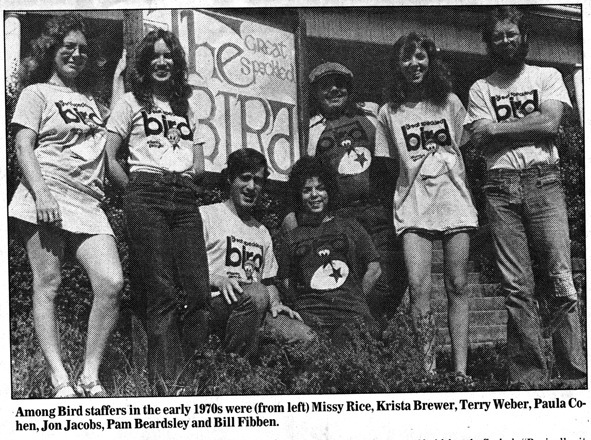

When the hip community began expanding and gaining visibility in Atlanta (circa 1969-70), much of the BIRD’S news coverage centered around the legal hassles that staff members and street people received from the city government through actions of the police . Changes came about in the BIRD’S coverage of women and the gay community as staff problems with sexism saw increased involvement by these oppressed groups (1970-71). A major change in direction with increased emphasis on local news coverage occurred in 1972.

Not too long after the BIRD got started, a phantom group called the Dekalb Parents League for Decency initiated a campaign that at first glance appeared to be directed against the BIRD. Various unsuspecting churchgoers and upstanding citizens of DeKalh County received a handbill through the mail in the Fall of 1968 condemning the Dekalb New Era (the governmental organ of Dekalb County), for printing the BIRD on their equipment. The handbill was composed of clippings from the BIRD with certain “nasty” words underlined in pen. The group purported to be disturbed by the “sacrilege, pornography, depravity, immorality, and draft dodging which are preached in The Great Speckled Bird.” The immediate effect was to intimidate the New Era so that it no longer would print the BIRD. However, it seems that since the New Era supported [mystere2’s uncle] Clark Harrison’s campaign for County Commissioner, some astute political observers determined the handbill was a smear sheet against the Harrison campaign. Unethical political practices are infra-party affairs, perhaps, but state law prohibits the distribution of unsigned political material. The Dekalb Parents League for Decency somehow “failed” to include anyone’s name. The GBI, postal authorities, and the county sheriffs office got hot.

But when the investigations led to the Decatur courthouse and it looked like there was a possibility that high Democratic Party officials in Dekalb County were involved, all of a sudden they decided to investigate the BIRD for “obscenity!” (Especially since it might have been put together in the Dekalb County Courthouse using Dekalb County employees on Dekalb County time, possibly involving the County Commissioner himself— Brince Manning.)

The Atlanta Vice Squad questioned BIRD street vendors. News dealers cancelled their orders in fear. Some advertisers expressed hesitation. No printer within 100 miles would print the BIRD. It was a false issue, directed at the BIRD, instead of a campaign violation.

Threats of prosecution for obscenity by Fulton and Dekalb solicitors and acts of harassment by various law enforcement agencies in the city and two counties motivated the BIRD to file suit on November 15, 1968. The BIRD sought a restraining order against obscenity prosecution, which was refused, although the judge promised no prosecution would be allowed before the court could be convened to rule on the constitutionality of the Georgia statute on obscenity.

At the trial, emphasis changed from the BIRD’S reprinting the smear sheet to a cartoon, entitled, “Anal-land’ that it had run. The Georgia statute on obscenity includes a “shameful or morbid interest in…excretion” as well as sex. As described by a BIRD writer, ‘Anal-land’ used as its comic vehicle graphic displays of and common language for that excretion politely referred to as defecation.”

Five months later the court ruling came: “In consideration of the facts of the case sub justice, we are of the opinion that THE GREAT SPECKLED BIRD is not obscene as that term has been defined in Roth supra, and its progeny, and is constitutionally protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.” -(Signed) Lewis R. Morgan, United States Circuit Judge; Newell Edenfield, United States District Judge Albert J. Henderson, Jr., United States District Judge.

The BIRD was not guilty of any of the politically contrived “obscenity” charges leveled against it at this time. But it was guilty of spreading sexist attitudes through its classifieds section. The classifieds were 50 cents a line, and before long the personals section had expanded considerably, requesting young, hip. white, females to move in free of charge and do housewifely chores. Other ads appeared that exploited the gay culture. Street sales benefited from the appeal of these sex ads. Even today the BIRD has to contend with this reputation. The Women’s Liberation Group in Atlanta (and many letters to the BIRD) complained about such ads. In 1970 these ads were eliminated, classifieds were made free (!!’). The BIRD now applies the same standards to ads as to articles, not purposely printing anything that is Racist, sexist, imperialist, classist, ageist.

In the early issues of the BIRD the nude women (photos and drawings) were not lewd, but of the artistic variety, done, in fact. by art students or self-styled artist. The BIRD offered an outlet for their publication. Explanation of the profanity printed was that the words had political connotations and were not to be taken literally.

“UP AGAINST THE WALL, MOTHERF_CKER”

“UP AGAINST THE WALL, MOTHERF_CKER”

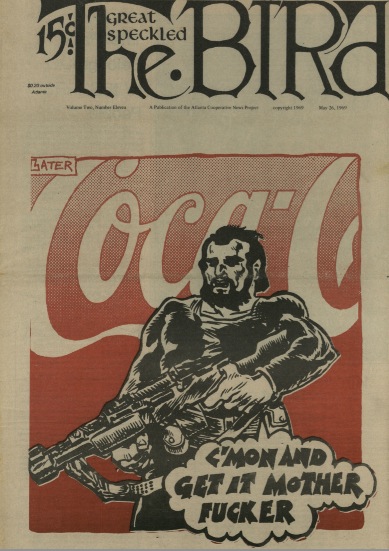

“Hello, I’m with the company that handles Coke’s advertising and they’re all very upset about this week’s cover of the BIRD. They want me to get a copy. Where can I get one?” That was a call received on Friday, May 23, 1969, the day after the BIRD with the popular Trashman comic book cover appeared: Super Street Man up, against the Coca-Cola wall motherfucker. Later, word came that “Mayor Allen is hopping mad about that cover and has ordered the city attorney’s office to prepare indictments against the BIRD.”

As one BIRD writer observed at the time, “Interesting chain of cause and effect; Coke hollers and Ivan dances. Good ole government of the interests by the interests, and for the interests. Now we must confess, we didn’t overhear Woodruff calling Alien. Most likely Woodruff didn’t even need to call Alien. I mean everybody in the Atlanta ruling class knows ‘Thou shalt not take Coke’s name in vain.’

The BIRD staff had had a difficult time in deciding whether to run the controversial cover. From the beginning the BIRD has been run on a cooperative basis: every person putting effort into printing and distributing the paper is part of the co-op and has a say in the running of the paper and the editorial content. At the time the dispute revolved around an aesthetic question of taste. According to the BIRD staffer quoted above, “There’s no use stirring up the local ruling class troglodytes unnecessarily.” But the reaction by the mayor absolved that question and made it a political issue, “The important fact about the most recent controversial BIRD cover is that it helps to clarify who rules Atlanta.”

The BIRD’S business manager (Gene Guerrero) and three BIRD sellers were charged with the two counts of selling obscene literature to minors and violating the city profanity ordinance. The sellers had been arrested with the aid of a 16-year-old “community service officer fink” who bought BIRD’S under the-watchful eye of city detectives’ cameras.

In court Judge T.C. Little queried: “What does the New Left have against a corporation with wealth? Do you own stock? Don’t corporations give everybody an equal vote through stock ownership? Would you just break up a corporation and give some to everybody? Doesn’t that boil down to socialism or communism?”

BIRD staffer Gene Guerrero answered: “Coca-Cola is and has been a very racist, viciously anti-union company. Their money is not honest money. They’ve broken Federal Labor laws over and over again in their attempts to stop unions. If in becoming a ‘newspaper empire’, we (the BIRD) were racist and anti-union then someone could and should have a cover like that about us.”

The charges were obscenity, but the prosecution of the BIRD was for political reasons, having nothing to do with obscenity. It was the policy of the city by this time to try hassling the BIRD out of business. The case was lost; $1000 fine per person (4). The BIRD appealed. However, for some reason-the city asked that the appeal be sustained— the convictions were reversed.

CLASS ACTION SUIT

Both the BIRD and the street people on the strip found themselves being hassled by the city government -and business community, basically because they were seen as threats to the status quo and tranquility. The BIRD collected affidavits from victims of official violence and harassment. During that same time period, the police provided more evidence, first with the August 4, 1969 Police Riot on 14th Street, then with the Sunday afternoon battle in Piedmont Park in mid-September. The BIRD filed a class action suit contending that there was a pattern of official harassment, discrimination, and intimidation against longhairs.

Aside from harassment from police for “selling without ii permit, the BIRD consistently had received delays and put-offs when applying for press passes. The “selling without a permit” ordinance was designed primarily to register door-to-door salesmen, not pertaining to the sale of newspapers. The Supreme Court had ruled (Lovett vs. City of Griffin, 1938) that requiring a permit to sell or distribute newspapers is an abridgment of First Amendment rights. In regard to the press passes, the harassment was not because the Police Department did not consider the BIRD a viable newspaper, but was an attempt to restrict the access of BIRD reporters-another First Amendment abridgement that continues periodically today.

Problems also arose in the cities of Savannah (1969) and Macon (1970) over the sale of BIRDs they were banned in these cities. Principals in high schools and some colleges in Atlanta and Dekalb County still continue to suspend students who are caught with BIRDs in their possession (not even trying to sell them).. Some area colleges have banned the distribution of BIRDs on their campus, just as former Lt. Gov. Lester Maddox banned BIRD vending boxes from the state Capitol .

MASSELL HASSELL

During the reign of Mayor Sam Massell One BIRD seller told a staff member, “Whenever you write anything about the mayor or the city, we get it on the street ten times worse.” On April 17, 19 72- “The Day Mayor Massell Tried To Kill The Bird”- calls began arriving at the BIRD that Vice Squad detectives were arresting BIRD sellers on charges of peddling without a license. By night nine had been arrested—no BIRD sellers were on the street. Street sales accounted for 50-75 % of the BIRD’S circulation during this period.

The story in the BIRD at that time began. “Harassment of BIRD sellers had picked up in December (1971) with our publication of the Slumlord List, a computer printout listing the largest owners of slum properties in the city, which the mayor had refused to act on and even denied existed. After that, the mayor’s office had stopped sending us press releases.”

A federal court suit was brought against Massell, Inman, and Vice Squad E.F. McKillop. When asked if he would check into the BIRD arrests, Massell ranted. “No, I’m not going to do anything. 1 don’t care what happens to them. They’re no longer a newspaper, they’re a hate sheet, so they no longer have any rights. They’ve yelled fire in a crowded theatre, and under .those circumstances, the right to free speech can be limited. It’s no longer a viable alternative newspaper. It’s just a matter of time until the newspaper closes.”

One cop told the seller he had arrested, “We never had the go-ahead before, but we do now, and we’re going to put the BIRD out of business. If you quote me in court, I’ll call you a liar’.” Vice Squad Capt. McKillop’s TV justification for the arrests was, “These people jump out into the people.” He told the BIRD lawyer that it the city really wanted to get the BIRD, they would have sent the fire inspector. He denied harassment charges, but was speechless when told a fire inspector had been at the BIRD house the day before.

The week after the sellers’ incident and the fire inspection, the US Post Office notified the BIRD staff that its newspapers would not be accepted for mailing if they included abortion referral ads (that had been printed for three years). An 1840 law was being used. A temporary restraining order allowed BIRDs to be mailed while the matter went to court. By October, 1972, the 1840 law was ruled unconstitutional. No one knew if the City Hall and Post Office hassles were related.

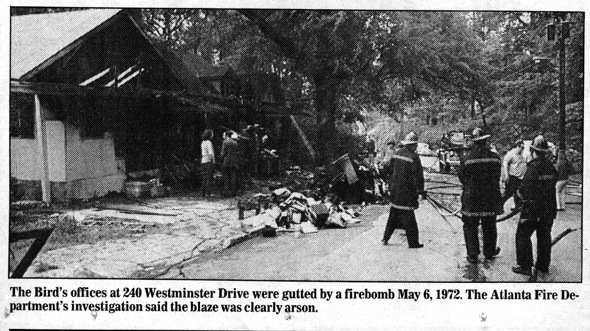

Then, on the next Friday a BIRD worker commented, “Do you realize we got through a whole week without a new hassle?” At 5 am on Saturday, May 6, 1972, a tremendous explosion erupted at 240 Westminister Drive with flames encompassing the whole house so that, within an hour, “there was nothing left of the front half but a charred shell.” The offices of The Great Speckled Bird had been firebombed. Before leaving the scene, Lt. J.A. Bird of the Fire Department told the BIRD staff that the way the fire burned, the noise the neighbors heard and the course of the fire indicated arson, probably ignited with something like a Molotov cocktail. The job looked like a professional one and thorough investigations turned up no evidence.

Then, on the next Friday a BIRD worker commented, “Do you realize we got through a whole week without a new hassle?” At 5 am on Saturday, May 6, 1972, a tremendous explosion erupted at 240 Westminister Drive with flames encompassing the whole house so that, within an hour, “there was nothing left of the front half but a charred shell.” The offices of The Great Speckled Bird had been firebombed. Before leaving the scene, Lt. J.A. Bird of the Fire Department told the BIRD staff that the way the fire burned, the noise the neighbors heard and the course of the fire indicated arson, probably ignited with something like a Molotov cocktail. The job looked like a professional one and thorough investigations turned up no evidence.

But by 11 am that morning, old friends, new friends, and former staffers arrived to give their support. “Already the BIRD was rising from the ashes” with temporary office space offered, benefits planned, time and services donated. In the BIRD story of the incident the comment was, “If the bomber meant to alienate the public from the BIRD, he failed totally. Not one caller said, “I’m glad it happened. You deserved it.” Instead comments were more like, ‘I’ve never read the BIRD, but I don’t like the idea of anyone trying to bomb you out. How can I send a contribution?”

The BIRD received tremendous support from the straight media, local bands, movement friends and others. A support letter from Julian Bond noted, “From its beginning as a small thorn in the side of the monopoly press to its present eminence as one of America’s strongest voices for the unrepresented, the BIRD has printed the news Atlantans couldn’t get elsewhere.”

The firebombing was traced to no one. Although the BIRD knew where a lot of its hassles were coming from, and it could easily associate the two, nothing could be proved. ‘

END OF THE BIRD? ,

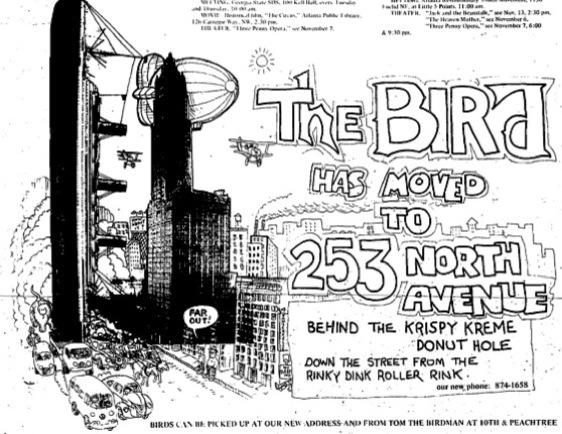

The BIRD had a real estate problem—now it was a definite risk. But somehow it found a house, its fourth, at 956 Juniper Street, one block from the almost deserted “strip.” It was a funky old house with leaded ornate windows. From here the BIRD continued to cover Atlanta’s news in an alternative manner. But a new problem arose -the staff.

Back in 1970 two “raps” 6 months apart had appeared in the BIRD from the staff speaking to the readers with self-evaluation and showing somewhat the inside of the BIRD. One even noted, “People have wondered if we still serve any purpose.” But, the BIRD went through its changes on the surface—enough to keep it going several more years.

Then, all of a sudden (for some readers) in the January 15, 1973 issue the BIRD announced, “This is it Folks!…with the Jan. 29, Volume Six, Number Three, issue (to be available Jan. 25) the BIRD will fold its wings and cease to f1y.” The paper was not broke. Instead, “The people presently on paid staff are leaving the paper and no new staff members for the paper as it is have come forward.” Before leaving though, the old staff called a meeting of interested old BIRD folks-readers and workers. About 60 or 70 people showed up, shocked and willing to commit themselves to keeping the BIRD going.

The January 29, 1973 issue proclaimed, “REJOICE! The BIRD flies on.” The new BIRD staff renovated the BIRD offices, even throwing out the old liverwurst in the refrigerator. The staff had grandiose plans and big ideas. Some schemes worked, some didn’t; many never got to be implemented. All but one of this “new” BIRD staff have left by this time of the BIRD’S 7th birthday.

Many, probably most, of the problems facing the BIRD a year ago still stare the present staff in the face. Also, unlike previous staffs, the present one has to deal with a very bad general economic situation. But one fact has remained with-The Bird from the beginning; its purpose is to “print controversial or unpopular views and actively try to change our society, not to be a money-making operation.”

A BIRD statement made August 20, 1973, still pertains:

“In this world of corporate bigness, greed, private interest, exploitation, and cynicism, the BIRD stands in opposition, trying to tell the truth that doesn’t fit into the established interests’ world and trying to help build a consciousness and a movement to change this country and the world. We think that is something important to do.”

“But we do not have the power, wealth, and position to do it alone. We can only succeed as long as we have the support of the people who believe in what we are doing, take the time and effort to help us out—with money, information, news and reinforcement.”

“Almost all of the revelations that have come out of the Watergate hearings were known and reported in the pages of the BIRD long before they became public issues. The same is true of the recent disclosures of secret bombings in Cambodia as well as many other sordid tales of governmental corruption, deceit and dirty tricks, only now seeing the light in the established media. On the local level, it has been the BIRD that has covered such things as the Rich’s strike, the secret deals and maneuverings around the school desegregation plan and the upcoming mayor’s race, secret real estate plans to steal land from poor people for commercial developments, the hidden scandals of the police department and the attempt by ‘law ‘n’ order’ John Inman to exert dictatorial control over the police department, as well as many other stories too hot or too revealing for the bigger Atlanta papers.”

This time next year, the BIRD might not even be around anymore. This could have been said any of the last seven years, but now the problems are more serious. The paper has only one full-time staffer left, with many part-timers and volunteers helping to hold the operation together. BIRD staffers and friends are trying to solve its pressing economic problems, and need assistance. One overriding question must be asked: Does the BIRD really matter anymore? Do the issues of the times demand that it survive? If enough people answer “yes” to these questions, the BIRD will survive its latest crises.

—j.d.cade