Miller Francis was at most basic, the music reviewer for The Great Speckled Bird. He is almost the first journalist to note Duane Allman and The Allman Brothers Band as something special. Rolling Stone Oct 4, 1969 pg. 18 Excerpt From The Underground Press ( a special report) [WHITE RACISM IN OURSELVES] One of the best rock and roll writers the underground has produced is Miller Francis, Jr., of The Great Speckled Bird in Atlanta. Francis is unique in his ability to place rock in the perspective of the revolution. Equally committed to the Movement and to rock and roll, Francis demands nothing but the best from both. This was how he reviewed the first MC-5 album: “The new, long-awaited MC-5 album is a disaster. Its very existence demonstrates perhaps the greatest weakness of the Movement in this country: its inability to understand, thus to make use of, the communications media, particularly the one that is by its very nature a ‘Movement music’—rock and roll music … At its best the MC-5 is an emasculated version of what the Who did years, ago; at its worst it is a pasty  faced derivative of black music (as if we needed yet another minstrel group!). The MC-5, who I understand were a white rhythm and blues group before they were ‘revolutionized’ by John Sinclair, have simply wheeled their grimy Detroit vehicle up to a Black Power station and said ‘Fill ‘er up.’ They play with their hands and feet, not with their guts and soul. They are smug, not proud . . . That white radicals can be turned on by this farce sadly demonstrates how far we must go before we can approach the problem of white racism in ourselves and in our communities without guilt and intimidation.”

faced derivative of black music (as if we needed yet another minstrel group!). The MC-5, who I understand were a white rhythm and blues group before they were ‘revolutionized’ by John Sinclair, have simply wheeled their grimy Detroit vehicle up to a Black Power station and said ‘Fill ‘er up.’ They play with their hands and feet, not with their guts and soul. They are smug, not proud . . . That white radicals can be turned on by this farce sadly demonstrates how far we must go before we can approach the problem of white racism in ourselves and in our communities without guilt and intimidation.”

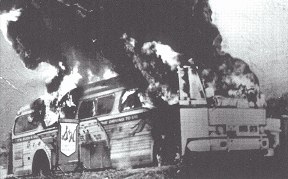

Miller Francis grew up in Anniston, Alabama in a working class family. He was in high school when a Freedom Rider bus was attacked and burned just outside of town. Inspired by Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, he studied fiction writing at the University of Alabama. He watched as Governor George Wallace took his stand for racial segregation in the schoolhouse door, and he met Vivian Malone and James Hood after they were admitted as students. He joined thousands at a rally in the former capitol of the Confederacy to welcome those who had marched for civil rights from Selma to Montgomery.

Miller Francis grew up in Anniston, Alabama in a working class family. He was in high school when a Freedom Rider bus was attacked and burned just outside of town. Inspired by Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, he studied fiction writing at the University of Alabama. He watched as Governor George Wallace took his stand for racial segregation in the schoolhouse door, and he met Vivian Malone and James Hood after they were admitted as students. He joined thousands at a rally in the former capitol of the Confederacy to welcome those who had marched for civil rights from Selma to Montgomery.

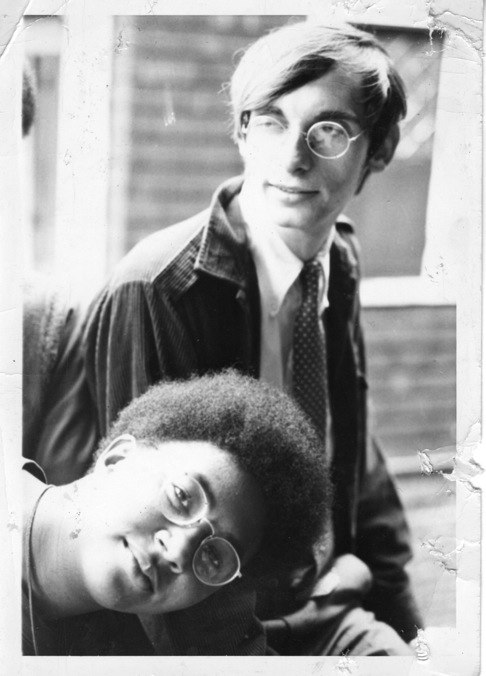

Freed from the bullying that had plagued his hometown years, Miller came out to his college friends and soon developed a “second family” of freethinkers, misfits and hippies. At his Army physical, after much soul-searching, he declared himself homosexual, and because of his opposition to the Vietnam War, a conscientious objector. To his surprise, the Army responded by denying him either status, and in 1967 he refused induction into the  military. Intending to leave for Canada, he married his best friend in a large, public Wed-In on the campus quadrangle, held on the release date of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. After deciding to stay in the US and fight his case in court, and he settled in Atlanta. There, he was arrested, and the ACLU provided legal defense. When the Army ordered a second physical exam, as required by Alabama law, he was declared 4F for reasons of health, and all charges were dropped only weeks before trial was to begin. As forces for radical change gained momentum in the Sixties, Miller moved from fiction writing and be

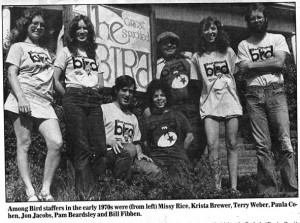

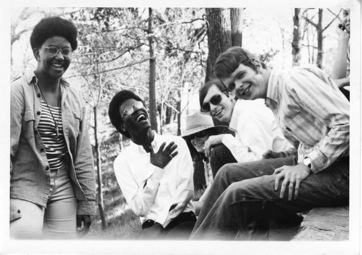

military. Intending to leave for Canada, he married his best friend in a large, public Wed-In on the campus quadrangle, held on the release date of The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. After deciding to stay in the US and fight his case in court, and he settled in Atlanta. There, he was arrested, and the ACLU provided legal defense. When the Army ordered a second physical exam, as required by Alabama law, he was declared 4F for reasons of health, and all charges were dropped only weeks before trial was to begin. As forces for radical change gained momentum in the Sixties, Miller moved from fiction writing and be came more active politically, writing only non-fiction, and continuing to demonstrate for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. He lived for a time in an Atlanta commune called The Heathen Rage, and wrote music and film reviews for The Great Speckled Bird, a weekly underground newspaper with national impact. Some of his articles were reprinted by other underground papers, and he also contributed briefly to Rolling Stone and Creem (including a review of Music To Eat by The Hampton Grease Band). He covered national events such as the Woodstock Music Festival, the Memphis Blues Festival and the Ann Arbor Blues & Jazz Festival. His enthusiastic “discovery” account of The Allman Brothers Band’s first performance in Piedmont Park is still being quoted (Scott Freeman, Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band). As early as 1969, Rolling Stone Magazine called Miller “one of the best rock and roll writers the underground has produced. . .unique in his ability to place rock in the perspective of the revolution”. In his book on the underground press, The Paper Revolutionaries, Laurence Leamer called Miller

came more active politically, writing only non-fiction, and continuing to demonstrate for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. He lived for a time in an Atlanta commune called The Heathen Rage, and wrote music and film reviews for The Great Speckled Bird, a weekly underground newspaper with national impact. Some of his articles were reprinted by other underground papers, and he also contributed briefly to Rolling Stone and Creem (including a review of Music To Eat by The Hampton Grease Band). He covered national events such as the Woodstock Music Festival, the Memphis Blues Festival and the Ann Arbor Blues & Jazz Festival. His enthusiastic “discovery” account of The Allman Brothers Band’s first performance in Piedmont Park is still being quoted (Scott Freeman, Midnight Riders: The Story of the Allman Brothers Band). As early as 1969, Rolling Stone Magazine called Miller “one of the best rock and roll writers the underground has produced. . .unique in his ability to place rock in the perspective of the revolution”. In his book on the underground press, The Paper Revolutionaries, Laurence Leamer called Miller  “the most articulate of the cultural radicals. [He] maneuvers the symbols of cultural radicalism with the subtlety and sureness of Marx working with the tools of economic determinism.”

“the most articulate of the cultural radicals. [He] maneuvers the symbols of cultural radicalism with the subtlety and sureness of Marx working with the tools of economic determinism.”

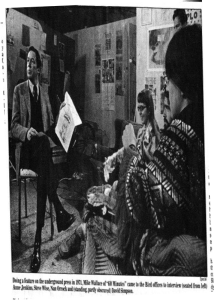

As new social movements began to develop, Miller wrote articles articulating the oppression of women and homosexuals, contributing some of the earliest statements of what soon came to be called the Gay Liberation Movement. Miller was divorced in the early 70s. For several years, he worked as a legal secretary at the Southern Regional Office of the ACLU and the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, and later held a number of different jobs–mill worker, county court transcriber and computer typesetter. After he left The Bird, he visited then-socialist China in 1973 as part of a delegation from the U.S.-People’s Friendship Association. As the era of the Sixties ebbed, Miller broke from identity politics for a broader vision of social change. From 1982 to 1996, he was DJ/host of Revolution Rock (By All Music Necessary) at listener-supported radio station WRFG  Atlanta 89.3 FM. In addition to playing punk rock and other forms of music on the cutting edge at the time, he conducted in-depth interviews with world class musicians such as Fela Kuti, Henry Rollins, KRS-One and The Clash’s Joe Strummer. Promoter Steve Harris described Revolution Rock as one of the shows that “exemplify radio pushed to its highest potential. . .Francis’ well-researched and tasteful presentation allows the music to communicate the message, avoiding the obvious pitfalls of political proselytizing.” Miller lives in Atlanta and is currently separated. For over twenty years, he has worked in the video library archives at CNN. In a return to fiction writing, he spent the last several years completing a novel, If Heaven’s Not My Home, which is set in a small town in Alabama in 1957.

Atlanta 89.3 FM. In addition to playing punk rock and other forms of music on the cutting edge at the time, he conducted in-depth interviews with world class musicians such as Fela Kuti, Henry Rollins, KRS-One and The Clash’s Joe Strummer. Promoter Steve Harris described Revolution Rock as one of the shows that “exemplify radio pushed to its highest potential. . .Francis’ well-researched and tasteful presentation allows the music to communicate the message, avoiding the obvious pitfalls of political proselytizing.” Miller lives in Atlanta and is currently separated. For over twenty years, he has worked in the video library archives at CNN. In a return to fiction writing, he spent the last several years completing a novel, If Heaven’s Not My Home, which is set in a small town in Alabama in 1957.