Category Archives: Festivals

Talkin ‘bout My Generation

The Great Speckled Bird June 15, 1970 Vol. 3 #24 pg. 12

Talkin ‘bout My Generation

“I’m looking for me, You’re looking for you We’re looking at each other and we don’t know what to do;” -“The Seeker” by The Who

Our situation is different from that of our parents, and their parents, and generations upon generations of non-colored peoples of the West. Instead of millions of young “individuals,” what we have now is an entire generation moving headlong into a collective consciousness in which every division, contradiction and polarization looms large. On one level, there are the “hippies” and the “politicals.” Within the “hippies” are the peace freaks and also the street fighters. Within the “politicals” there are the “Marxist-Leninists” and “anarcho-syndicalists.” Within the “Marxist-Leninists” there are those who lean toward Mao and the Black Panther Party, and those who really warm up to Stalin, not to mention those who groove on Trotsky. Within the “anarcho- syndicalists” there are those who refuse to relate to print and organization at all and retire to the farm, and then there are those who still struggle “on the scene’ within established Movement forms and structures. A few of these still can dig Jerry Rubin, but others say even his “followers” are politically way beyond the adolescence of their “leader.” Some of these strains try to come together as Weatherman or White Panthers, but no one thinks that young people stand together.

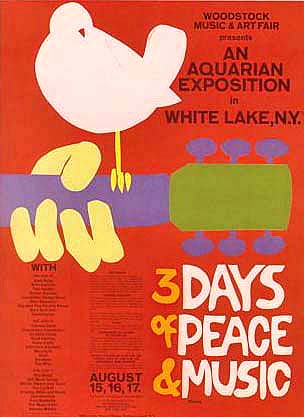

One of the worlds in which some of these groups, or “consciousnesses,” overlap is in the world of Rock and Roll music. The “freaks” dig it, live it, get their opinions, “the story,” from it. Some of them want and work for an anti-capitalist Rock & Roll Liberation Front:’ others don’t care too much about all those millions of dollars ripped off from us while we scrounge up meals and rent and bail money to survive in an anti- human capitalist economy. Both of these groups place great significance in the phenomenon of Woodstock, and the “politicals” within the “hippies” have even formulated a tribal concept of “nation” based on the event at White Lake, New York. The hard core “politicals” wish Rock music were not so loud, so omnipresent, and so goddam popular; they feel sure that the whole Rock & Roll lifestyle—dope, hair, nudity, communes, music, etc.—are all part of a capitalist diversionary tactic designed to channel energies away from “building an international socialist movement.””Woodstock”—and all it meant—is their NEMESIS. Those “radicals” who are more “liberal” than the hard core can take it or leave it, and sometimes they even smile on Rock & Roll as the best possible way to draw big crowds to hear the speakers they most want to push.

What is disastrous for the evolving youth consciousness across the Western world is the fact that this new generation does not see its parts as merely different, complementary elements of what is essentially the same thing—a new tribalized Western human being with, for the first time in centuries, political and esthetic consciousness capable of finding a meaningful role for itself in the Third World revolution is restructuring the globe with new priorities. The first generation of non-colored Westerners who can move beyond “MAN” and ”woman” into Sister/Brother.

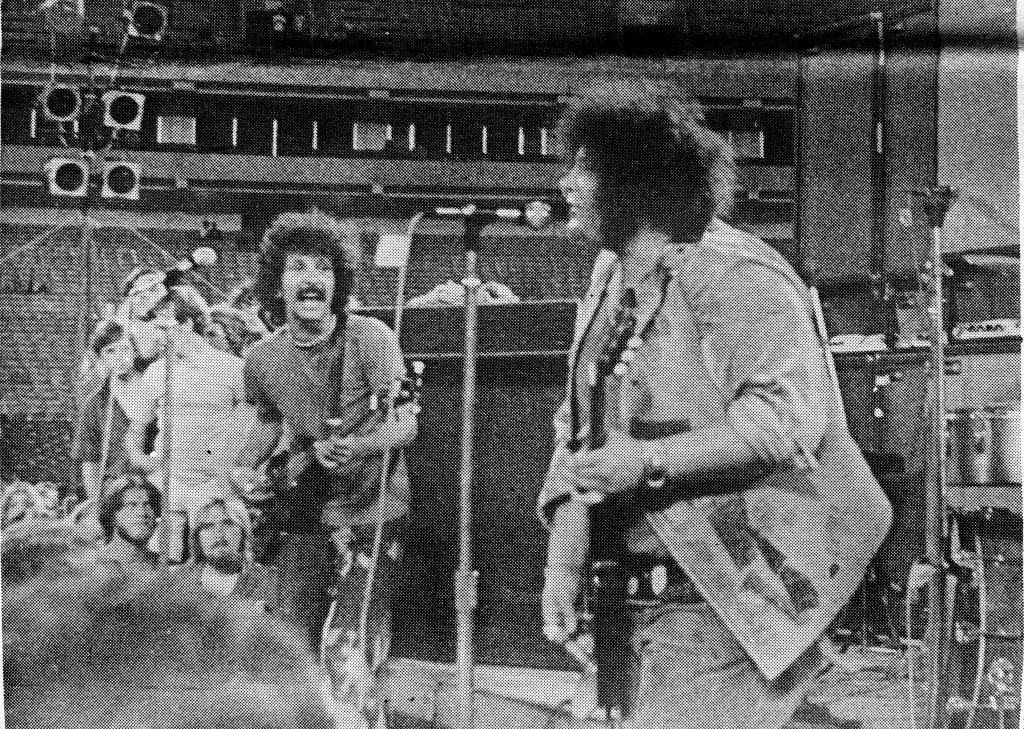

At Woodstock, perhaps the most important single event occurred— ironically— in the form of violence. And not violence against Amerika but rather violence by brother against brother. During a beautiful set by The Who, including much of Tommy, Abbie Hoffman who was bumming on acid, a fucked-up head, and suffering from Future Shock because he didn’t really understand what was happening, leapt to the microphone and piously announced, “I think this is a pile of shit!” Abbie tells his version of the incident in Woodstock Nation, although I don’t believe he claims this particular statement (“Free John Sinclair” is what he does claim, and that’s a lot more dignified and responsible). Nevertheless, I’ve got it on tape, and hundreds of thousands of people freaked out on this sweeping condemnation of the music of The Who, Woodstock, the “cultural revolution,” etc. Considering the level of consciousness those hundreds of thousands of young people were at, the exploding sunrise, Tommy, what Sly and the Family Stone had done earlier, Hoffman’s seizure of the mike and his “pile of shit” denunciation were incredible acts of violence.

The second act of violence was physical: Peter Townshend, dean of Rock guitarists, himself bumming on a dose of acid he had unwillingly sipped from a cup of coffee, quite aware of the contradictions at Woodstock, struck Hoffman with his guitar-hard, heavy, like the music. And, ironically, a lot of folks dug it, especially the peace freaks who wanted to see Hoffman as an “outside agitator,” a scruffy, insolent, ego-tripping thorn in the side of Woodstock the “nation” he would later name and define for Amerika in the Chicago Conspiracy trial.. But nobody knew quite what to make of the violent confrontation between these two brothers, both of them for some time figures for emulation by the masses. One the author of Revolution for the Hell of It, the other the composer of “My Generation,” both distributed by Amerikan capitalist industries, both more than subversive. Most accounts of Woodstock didn’t even report this incident; some did, but didn’t know quite what to make of it. “Politicals” who had no head equipment with which to understand the Woodstock phenomenon could relate to nothing at all except this incident, but even they had trouble claiming it because they couldn’t accept Abbie Hoffman as one of their own. Problems, problems! Most people preferred not to relate to the incident at all -it didn’t “really” happen, and even if it did, it was only an isolated incident. The golden legend of Woodstock was so much more beautiful without it.

But Hoffman himself was so freaked out that he had to write an entire book articulating, to himself and us, what took place. Woodstock Nation is about a bummer at White Lake that “culminated with a battle onstage with The Who.” “One of those rare acid trips when everything caves in. I learned enough shit from it, though, that maybe it wasn’t such a bummer after all. All I can say is, man, I took a heavy trip!” Hoffman says the confrontation with Townsend “symbolizes my amity-emnity attitude toward that particular rock . group and the whole rock world in general. Clearly I love their music and sense in it the energy to liberate millions of minds. On the other hand, I feel compelled to challenge their role in the community, to try and crack their plastic dome.”

Peter Townshend, who demanded The Who’s fee for playing at Woodstock and thus encouraged other Rock groups who played there to do the same, was denounced as a “Rock capitalist,” a pig, a foppish dilettante “artist” who was more interested in counting coin and playing Tommy for furs and tuxedos in ruling class opera houses than he was in relating to “the needs of the people.” “Oh fucking hell,” Townshend says now (in Rolling Stone interview, May 14, 1970), “Woodstock wasn’t what rock’s about, not as far as I’m concerned. Quite honestly, I mean knock for knock, everything Abbie Hoffman said was very fair.” In addition, he says that The Who, in the wake of Altamont, will do free concerts, “but only concerts for causes.” “All kinds of bust funds. Good way to give Abbie Hoffman another punch in the stomach would be to give him the returns from a bust fund. I think I’d do it for him if he asked me.”

Regardless of what “politicals” may think or say Rock & Roll is more important to young people now than it has ever been, although the kind of importance it has is changing radically. At the same time. Rockers are realizing—listeners, musicians and middle men alike— that Rock & Roll must move beyond its consumer capitalist foundation or we will see summers of barbed wire Rock festivals, “Woodstock reservations,” and youths divided into Freaks and Consumers (one will be busted, jailed and murdered; the other will grow into loyal Amerikans with long hair). It may very well be that understanding the violent confrontation between Abbie Hoffman and Peter Townshend at Woodstock can help us understand more of what we are and what divides us, what we have to do before we can join in changing the world we live in. If, however, this contradiction among the people is not resolved, and we do not stand united Vas a Western revolutionary youth movement, then we will not be able to struggle to win a place in the new world. And that’s what it’s all about.

On Monday, June 22, at 8:30 we will have a chance to hear The Who direct, live, up front, here in Atlanta at the Municipal Auditorium. The Who are true children of Marx and Coca-Cola, and together they play a Rock & Roll that might be called Disciplined Sensationalism, a furious delight on any level-perverse pop lyrics, blues-rich Rock guitar, heavy bass and ferocious drumming. Most groups sweat to achieve wildness and fury; The Who, rather, tempers and disciplines their spirit so that every note, no matter how loud or exciting, is part of a whole of unblemished perfection. Pick up on their new single, “The Seeker”—fantastic!—and a new masterpiece album, The Who Live at Leeds. If you have heard Tommy, the old things, plus what The Who are done on the new live album, and you still don’t go to hear The Who at the auditorium, then I can’t imagine while you’ve read this far in the first place. Why doncha all just just f-f-f-fade away…

—miller francis, jr.

DOWN BEAT: Do you feel rock has anything to do with revolution? I’m referring to people like the MC5, for example.

TOWNSHEND: It hasn’t anything to do with it. The MC5 are presently trying to get out of that. They were a vehicle for revolutionaries who were interested in their own remuneration and their own good times. John Sinclair-ever since he was 15, every minute of his life he was free. Some people can do that, take care of their own problems, never need to work, and get along. Abbie Hoffman, too – he can take bad trips and never do a stroke of real work and live and go through his own particular kind of existence and come out. The MC5 were manufactured; at that point they were a good rock group, but they were used Revolution is something that happens. Wearing a badge saying “Revolution” means nothing.

Downbeat: What’s necessary for Amerika , if not revolution?

Townsend: What is necessary is a revolution, but you don’t get revolution by incitement. In a way every revolution that has ever happened has been incited: people have sat in back rooms and talked about it before it happened. In the US the revolution is a universal revolution. The whole of Amerika wants to have a revolution. Middle-aged people want a revolution to reduce the generation gap, which sours them – really sours them. Amerika has lost every ounce of prestige it ever had.

Amerikan youth has done nothing nothing— but live off the Amerikan system. That’s why in European universities Communist Russia and Mao have more respect than Amerikan youth. Chairman Mao has done quite a lot for change in his country.

DOWN BEAT: What about the Moratorium activities in Washington?

TOWNSHEND: I always feel two ways about demonstrations. Demonstrations are pointless, and yet I still feel myself doing them, just like I still feel myself writing songs about changing society. I know perfectly well nothing at all is going to change because of it. Still, if I had nothing better to do, I would be down there with the demonstrators. Cops have broken my head dozens of times, and I’ve always come out laughing. I always dug the cops, I dug what they had to do, I dug why they arrested me. But demonstrations are too impersonal, wars are too impersonal; confrontation is better, man-to-man.

DOWN BEAT: If rock isn’t revolutionary or even political-

TOWNSHEND: The best rock isn’t.

DOWN BEAT: – then what do you want your music to do?

TOWNSHEND: I want it to do what it already does.

-excerpted from Down Beat magazine, May 14, 1969

The Producer of Woodstock talks

(The following dialogue with Bob Maurice, producer of the Woodstock film, is an edited version of a long interview taped last week at the Marriott.)

MAURICE: What we tried to do was to pass on the experience of Woodstock, really try to create an environment in the theater which would make people forget that they were in a theater and [which would] really give them as much as possible the same experience as actually having been at Woodstock. And that’s, of course, quite cunning because that’s much more effective than propaganda. We’re passing something on. It really is dissemination in the exact meaning of that word. I wouldn’t call it propaganda because we’ve left out our point of view. We haven’t interpreted Woodstock.

There was organization in the filming, there was structure. But I think that there was nothing organized about Woodstock. It really was an historical accident, not a proselytizing event. It wasn’t a peace march, and it wasn’t a demonstration, and it wasn’t in any sense an “example.” It wasn’t consciously done. There was no prior intent or motivation on the part of anyone who went up to Woodstock to create Woodstock. I think Woodstock is the one of the few instances in which all of the rhetoric of the past 10 years or so has been fulfilled. So that for once instead of talking about what was desired or demonstrating in favor of a position, we simply just went ahead and did it. Because precisely what was going on there was that everyone had already accomplished everything that the rhetoric was about. Woodstock in a sense is “after the Revolution”-that’s what it will be like, after everything has changed. You know, it’s senseless to indulge in more rhetoric so all that you can do about something like that is just pass it on. Do I make myself clear?

BIRD: I think so. I just have a hard time reconciling that with my experience at Woodstock. It is true that feeling you are talking about, but I couldn’t help but think-perhaps you felt it too-that the helicopters circling over that crowd—the same type of helicopters that three months earlier had been clumping tear gas on Berkeley, or dropping marines in Vietnam. You are trying to say that people didn’t feel this. The fact that people were getting busted right outside by the New York State Police, people were being stopped with searchlights and shotguns-it happened to us as we were leaving.

MAURICE: Every review that I’ve read objected to our point of view and criticized us for adopting a view which they see and object to. The interesting thing is that none of the reviewers agree on what our point of view is. What’s really going on is that each reviewer is merely seeing his own tendencies in the film and then accusing us of it. Everyone sees a point of view in the film. Well, there really isn’t. If a point of view film had been made of Woodstock, it would have been incredible. It would have had martialed so much material towards one end that you would have a very directional film. And now you don’t. One critic said the film wasn’t “organized,” and what he means by that is that it doesn’t make a single point, it doesn’t begin with a point and then illustrate or support it. Well, reality isn’t like that. Woodstock wasn’t like that.

I guess the core of Woodstock was three or four days. We shot those three days just about in their entirety, and we were up there about a month beforehand shooting all the preparations and the townspeople and we stayed afterward and shot the cleaning up. Well, that 120 hours we made a three-hour film. So a lot of stuff was left out. Well, you can’t accuse me of having left out 117 hours of film on purpose.

And the mud has not been left out by any means. The Army thing is not left out, but you don’t have to devote a half-hour to make a point. You can make a point in a 10-minute shot. If the person who is watching is intelligent, he will see it. There’s a shot in that film of an Army helicopter landing. You know, a Army helicopter lands with machine guns sticking out the front. You know the army was there. I know the police were there because I had to deal with them also. What you don’t know is that the F.B.I, was there; I had entanglements with them. It’s true that it was potentially a massive bust, and a very unpleasant thing, and the latent paranoia was quite strong. It did work out. Holy Christ! Think of all of the dope that was at Woodstock and how few arrests there were— and they were all outside the place. It’s true that there is nothing in the film that shows police arresting people, and I think that the reason for that is that none of the 18 cameramen/ directors witnessed any such event. I think the only time that happened was when people were leaving and it was all over. But what we saw was cops who were turning on. New York City cops who were wearing those red Woodstock shirts, and I know the ones I saw were in the backstage -area, and you know they’re potentially friendly anyway because New Yorkers are so emotional and hysterical. By Friday they were joking and by Saturday the very, very pleasant atmosphere had gotten to them and they were turning on and enjoying it very much.

BIRD: I think you ‘re trying not to see, but I think you do see a really close connection between Berkeley, the garbage strike in Atlanta, the 21 Panthers in jail in New York, the fact that this film which is a film about 500,000 people and 20 entertainers, and what 40 people saw in their experience is now being sold to these same people for $3.50 a ticket. And at the same time many of these people who contributed so much to the film in some part through dope they used are in jail or need bail money. Do you see any relation between the film and the needs of the people in it? The fact that they need bail money? People in Atlanta need bail money. Are any places in the country doing benefits with Woodstock?

MAURICE: No.

BIRD: Is anything that is being taken out of the experience at Woodstock being returned to the people, other than the reliving of that experience?

MAURICE: Well, I don’t own the film. Warner Bros. does. Warner is engaged in putting film into theaters so that it can make money, and the theater owners show the film so that it can make money, and that is exactly the same situation that applies to the records of the artists who played at the festival. They make records to make money, etc.

BIRD: It seems a more direct utilization of the people at Woodstock than of the film itself.

MAURICE: Exactly. It seems that way, but it’s not. I really disagree with your phrasing that something’s “taken out” of Woodstock. Nothing was taken out of Woodstock. Nothing was physically taken. No one suffered a loss. No one experienced an inner emptiness or a physical alienation as a result of the making of our film. If anything, what we’ve done is the reverse. It’s a giving into—so you have to pay for it, right? You have to pay to get into the theater to see the film, but you’ve got to contrast that with getting in to see it for nothing—that’s impossible. $700,000 is a lot of money. I don’t have it, you know. I’ve got about $10,000. Warner Brothers is not a benevolent organization; it’s a business. It’s not interested in Rock festivals per se. It’s not interested in you or in me, or in anything —it’s a business, it’s got stockholders. And I was quite willing to make a deal with Warner Bros. because I wanted to make a film, and because I felt that it was important, it was important to me personally, and I also felt that if the film existed, and people saw it, even if they had to pay that that was better than its not existing and no one seeing it. Well, Warners put up the $700,000 because they’re—as you know, all of the studios are going broke, they don’t really have much money to play with either so they put the money up because they hoped to make more money. That applies to everyone.

Now about the other thing, the people who are in jail for dope busts, I agree. It’s one of the things that I feel very, very strongly about. I think it would be a very good thing if part of the money of this film were used to get some of those people out of some of those 30- year sentences. But there isn’t anything I can do about that. I mean, I’ve already done a lot in making the film. But my talents and energies, like everyone else’s, are limited. I can’t go on from that to, you know, a whole other kind of activity. I thought it was very important to make the film. It’s an honest film.

BIRD: I think it’s fairly obvious by now, considering the tremendous success of Easy Rider, that what you have turned over to Warners is one of the very few types of films that is going to make money now.

MAURICE: That’s bullshit.

BIRD: What happens after Woodstock, after Easy Rider? What is the next film going to be about?

MAURICE: But I’m a film-maker-I don’t give two hoots about Warners. If Warners goes out of business, that’s their problem.

WARNER BROTHERS: He doesn’t work for Warner Brothers.

MAURICE: The points are these: Warner Brothers did not make the film. They didn’t have anything to do with it. I made it, with my company. But Warners is in the business-of distributing films—they’re a distribution company. So, they pay for the cost of the making of this film and in exchange they can distribute the film. That’s fine with me. Because all I want is to be able to make a big movie about something I’m interested in, exactly the way I wanna make it. Which I got. Now what happens at Warner Brothers from here on in is of no interest to me. And I don’t work for Warner Brothers.

I’m very much of an outlaw anyway. I had to do incredible things to finish that film in, you know, my way. I must tell you that Warners did not want me to make the film which you will now see, they wanted something quite different. I wanted to make the film I wanted to make, and I did just horrible, horrible things to them, to beat them down, and intimidate them, and just generally scare the shit out of them. Because, I wanted to win.. .And I threatened to destroy the film, you know, unless they completely stayed out of it. fl I’m blacklisted at this point. But it doesn’t mean anything at this point to me, because all of our enjoyment comes from doing things outside the system which is also where our power comes from.. .The fact is that nobody else could have made that film but us.

I mean literally—nobody else could have done it. It was just too insane, and required a kind of adaptiveness and flexibility and tirelessness. Wadleigh, the guy who directed it, is incredible.

BIRD: Before W., China would have been the place where you would hear of 500,000 people in one place. It’s shocking for Americans to think of that many people in one place, especially for that long. And when you make a film about that, you almost have to relate to what those people do after that film. It’s entirely different from making a film about just a few people. It doesn’t let you go when you get involved with that many people.

MAURICE: I think the thing that’s bothering you is this thing of “co-opting,” which happens all the time

BIRD: I don’t think you can co-opt what happened at Woodstock.

MAURICE: You’d have to be pretty slick to do it. Because one of the things that Woodstock was, by definition, was a rejection of exactly that, a rejection of ultimate values. Again, it was not a proselytizing situation. People were not saying. This IS the thing to do; this IS the way to live at all. What they were saying was just for three days we’re not going to tell anyone else what to do and we don’t want anybody to tell us what to do. We simply want to enjoy ourselves. You can’t co-opt. Because it’s not there. It’s like trying to hold sand between your fingers. If it had been a radicalizing, a proselytizing event, if it had had intellectual content, one could co-opt that position and say, “I approve of this position.” Like Johnson did. And they could say well, great, I approve of this, too. But there was no position taken at Woodstock.

BIRD: In San Francisco, demonstrations are being held against this film…

MAURICE: And in Los Angeles.

BIRD: What these people seem to feel is that well, you said that nothing was taken out of Woodstock. Yet whatever it was that was done with the experience of Woodstock is being sold at a very high price. Do you lay all of the value of the film to the people who made it? Or do you see the people who made it as rather disseminators? Or go-betweens? The techniques that you use, the way that the people who made this film have been able to bring out what happened at Woodstock are extremely powerful techniques. Warner Brothers doesn’t understand them. You talked before about the use of power and how you fucked Warner Brothers. Certainly you can look at this film-as-a tremendous type of power. The economic returns from it are still completely in the hands of Warner Brothers.

MAURICE: I happen to be one of those who believes that all reality is tainted, and that it is impossible to do anything which is not, in some way, either in the act or in its implications, tainted. It’s impossible to design, or do, something which is entirely good. Because I really feel that OUR definitions of good and evil are exactly that. They are imposed, we really want them to be imposed on a reality that defies that, which doesn’t by nature really very clearly fall into good and evil. And the consequence of that, at least for me as a human being, is that I am incapable of doing anything which I am sure is clearly good and only good and not in any way evil. I’m sure that everything that I do is potentially in its implications in its eventualities in . some way is going to not be to someone else’s advantage or negative in some other way, which I don’t even know about. The only way in which you can avoid doing evil is by doing nothing. By absolutely avoiding action.

I’m convinced that contemporary radical politics is purely Christian. It’s one of the manifestations of Western Christianity. And it’s that dichotomy of good versus evil, essentially a Christian one, and it’s idealistic, and it’s the belief that you really can separate out a principle of evil and a principle of good and call one God and the other the Devil and eliminate one and have a purely good structure of reality. Well, I don’t think that’s possible. And it’s exactly that that is the basis of Communism. You know. Communism defines a specific social order as the good, and the other thing as the evil, and it very naively believes that you can separate them out physically. But you cannot cut it with a knife. People are too complicated for that. What we’re doing in this conversation you may feel is very very good. It may be very bad for me! You know, in some way that you’re not aware of. Vice versa. I gave that up a long time ago. I’m incapable of doing something which is not open to reproach, which isn’t screwed up in some way. You’re looking for, you’re asking too much of me. You really are. If I had done all the things which are ancillary, which surround the making of the film itself, I wouldn’t have had any time left to make the film.

WARNER BROTHERS: I hate to interrupt you…

BIRD: I agree with you that there is a problem with the radical movement in the U.S., but we should narrow that down and say the white radical movement. But I think the problem is the opposite of what you are talking about. To distinguish between evil and good is a luxury. To be able to think about an absolute good and an absolute evil—And the place you have to look for more real politics and less rhetorical polemics is TV Black people. You ‘re just indulging yourself in all this talk about good and evil.

MAURICE: But what’s wrong with bloodless revolutions?

BIRD: I wasn’t even discussing that. It’s the use of power—that film is a very powerful thing, /understand quite well that Warner Brothers can distribute it quite easily and make money off of it, that’s not the point. The point is that none of that money is coming back to people, not the fact that Warner Brothers is making money off it. God knows a lot of people are making money a hell of a lot worse ways than that, but that’s not the point. The point is that NONE of that money is coming back.

MAURICE: I wouldn’t use the phrase “coming back,” because the money doesn’t belong.. .the money didn’t come from the places you want to send it back to. When you buy gas, the money comes from you, when you buy food, it comes from you, when longhairs, dopers and Blacks buy fountain pens and tires and all of that, it comes from them. You could just as well speak about sending that money back, too. I think there’s a failure in logic that makes you want to say, Woodstock’s different, it belongs to the people. That’s bullshit! I reject that personally. It doesn’t belong to the people—1 made it. Insofar as I made it, it belongs to me. Beyond that, I would very much like to see everybody be able to go see Woodstock for nothing, but that’s only because I’d very much like everybody to be able to see all movies for free.. .But I can’t really answer what you’re saying, and I can’t assume the guilt, either. You’re trying to say that I’m…

WARNER BROTHERS: Bob, excuse me…

MAURICE: Oh well, okay.

WARNER BROTHERS: We’re on a real tight schedule. I’m sorry, do you mind?

Woodstock The Movie

The Great Speckled Bird May 30, 1970 vol 3 #18 pg 4

Woodstock (the movie)

Woodstock is an amazing piece of technology, one of the most important films ever made. We have long been accustomed to experiencing films as primarily visual, with sound accompaniment. Woodstock escalates the film experience to a tactile level—the “visual” and the “aural” are merely two modes of an integrated experience of what the audience “feels.” The quality of the camerawork and the editing, the way in which the hours and hours of footage have been put together, are among the finest in the history of film. But somehow what you “see” in Woodstock is only a small part of what you experience, much the same as when you dig a Rock concert—there’s the dope, the lightshow, the people, the setting, the weather, etc.

Woodstock is an amazing piece of technology, one of the most important films ever made. We have long been accustomed to experiencing films as primarily visual, with sound accompaniment. Woodstock escalates the film experience to a tactile level—the “visual” and the “aural” are merely two modes of an integrated experience of what the audience “feels.” The quality of the camerawork and the editing, the way in which the hours and hours of footage have been put together, are among the finest in the history of film. But somehow what you “see” in Woodstock is only a small part of what you experience, much the same as when you dig a Rock concert—there’s the dope, the lightshow, the people, the setting, the weather, etc.

The professional film-makers who produced and executed this documentary knew exactly what element was needed to change the sense ratio of the ordinary film experience—volume. The sound used in Woodstock is louder and of a higher quality than films have known before. Hollywood epics just throw these tools away. Just as Rock & Roll was at the center of the original Woodstock experience, you might even say that the “sound” of the film Woodstock is dominant, and the visuals of the film more of an accompaniment to those sounds than the other way around. In other words, Woodstock succeeds in embodying an accurate sensual perspective of Western youth-the first film, with the possible exception of 2001, ever to do so. Easy Rider, Blow-Up, Bonnie & Clyde, Z, and Zabriskie Point, though extraordinarily popular with young people, all use more or less conventional frameworks for their unconventionalities; at most they signified new directions rather than completed destinations. 2007 experimented with sound and it attempted to go beyond Sight and Sound to include an exercise in the colors, designs and shapes of Touch. Woodstock goes further.

Woodstock is a brilliant success as far as Form is concerned; its Content falls far short of what these new technical proficiencies are capable of—not so much in what was there in the film but in what was not there. Woodstock is in many ways an extremely subversive film, not in what it “contains,” but rather in what is “is.” The potential for mass experience foreshadowed in the Country Joe and the Sly and the Family Stone sequences are staggering. Implicit in Woodstock is the possibility of producing films to “accompany” recordings so that the record itself would merely be one aspect of an integrated sensual trip. Other potentials have almost no limit. The kids who see Woodstock will not be able to go back to more ordinary films and will demand new, mind-blowing forms that cross beyond the barriers separating different media. The technical potential is just overwhelming. Too bad that technical trip didn’t expand the human consciousness of those who made it: they miss the whole point of the Woodstock experience.

Trying to “interpret” the mass experience at Woodstock has been no easy task. In the massive volume of words inspired by the event, there were almost as many different explanations and interpretations of exactly “what” happened as there were people present at the event. Abbie Hoffman wrote an entire book trying to crawl his way through a maze of confusion, misunderstanding and sensual overload—he got out but by the skin of his teeth. Others have been less challenged by the experience of Woodstock and have contributed less to an articulation of what it all “meant,” but the producers of Woodstock (the film) have chosen the most conservative, least offensive perspective in which to view the three days of “fun and music.”

Trying to “interpret” the mass experience at Woodstock has been no easy task. In the massive volume of words inspired by the event, there were almost as many different explanations and interpretations of exactly “what” happened as there were people present at the event. Abbie Hoffman wrote an entire book trying to crawl his way through a maze of confusion, misunderstanding and sensual overload—he got out but by the skin of his teeth. Others have been less challenged by the experience of Woodstock and have contributed less to an articulation of what it all “meant,” but the producers of Woodstock (the film) have chosen the most conservative, least offensive perspective in which to view the three days of “fun and music.”

Gone is the incident in which Who guitarist Peter Townshend struck Abbie Hoffman with his instrument during “Pinball Wizard” for lamenting the absence of some sort of political stance at Woodstock; gone are the police hassles and busts outside the sacred area of Yasgur’s farm; gone is the two-hour Rock masterpiece given to the people there by the Jefferson Airplane at sunrise (including those “political” songs like “Volunteers of Amerika” and “We Can Be Together”); gone are the Grateful Dead, the Band, Ravi Shankar; gone are all the backstage, behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing by all the “HIP” capitalists who succeeded in making a fortune out of Woodstock. Absolutely and completely absent is any attempt to get at where all these kids came from.

How many veterans of Woodstock are or have been in jail or up before judges before and since Woodstock, and will be after they see the film made about them? Every attempt is made in the film to portray soldiers, police and representatives of the “system” as friends of the kids at Woodstock. No mention of what was taking place all around the farm, the searches, the longhair narks, the searchlights, the roadblocks, etc. Not that the groovy experiences of Woodstock did, not outweigh the bummers—it’s just that the people who made this film seem to have been trying to make a piece of non-struggle propaganda while claiming to have been merely “recording” or “reporting” an event. Nothing could be further from the truth: what went into this film was as carefully chosen as is possible in making a film. The incident in which a guy is rapping about “fascists” seeding the clouds functions in a very real, harmful way to discredit the whole perspective of politics. No accident that. Consider that Abbie Hoffman, who succeeded in articulating the experience of Woodstock within the context of the Chicago Conspiracy trial, is nowhere present in the film while such people as Bill Graham are featured. Consider that the only overtly “political” elements retained from the original are Joan Baez, who was safe and married and pregnant and nonviolent and singing “David’s” songs, and Country Joe and the Fish, whose FUCK cheer is a gas but whose Vietnam protest song seems harmlessly obsolete as far as where our heads are at NOW (and where Amerikan troops and war technology are now).

Woodstock will consolidate and crystallize a certain limited number of thoughts and feelings shared by young people all over the country and bring isolated areas and smaller towns into a national mass youth experience with values more common to New York, San Francisco and larger urban youth scenes; but the film does not go beyond this achievement. That’s why kids who have gone beyond the Content of the film are picketing against its rip-off aspects in some parts of the country, and kids who live in places where you can’t say Fuck (Worcester Counties all over Amerika), can’t wear long hair, and can’t turn on even on the smallest scale are demonstrating against city power structures which refuse to let it be shown. It is ironic that a film which is a celebration of the power of the people over an event which was intended to be a larger, but no more unusual than any other planned, profit-oriented “pop festival” is passively attended by masses of kids who are expected to pay $3.50 to $6 in order to see how groovy the Woodstock scene was when everybody got in free. FREE! If ever a film should be distributed for free admission, it is Woodstock. The film also gives the lie to all that bullshit about the promoters “losing everything they had.” If you think about the sound equipment used in this film, the cameras, the crews, the incredible, unbelievable amount of control over the finished product, what you know is that, for the Woodstock promoters, the experience there had much more to do with the film Woodstock than it did with the “music festival” at White Lake. Which is why the disaster at Altamont happened in the first place. In other words, the New York experience of fun and music is inextricably bound up with the California experience of bad vibes and murder, and any film that attempts to dig one without acknowledging the other is misrepresenting the truth.

When you leave the Rhodes Theatre and the manager hands you the Woodstock leaflet and a button reading Peace & Love, tell him to accompany you over to 11th Street some night when the pigs are coming down on Woodstock people, tell him to visit Vine City, tell him to ponder what happened to Meredith Hunter, a Black man, at Altamont, tell him to come with us to attend Aldermanic meetings where “loitering” ordinances are passed to keep us and Black people off the streets, tell him to remember the fate of the American Indian nation that once graced the land now labeled the “United States” and relate that genocide to what is happening to the Black Panther Party and to us, members of the Woodstock Nation all across the land yesterday, today and tomorrow. After he’s done this, ask him why you can’t accompany him to the box office while he’s counting the receipts, and get in on some of that $3.50 a head and turn it back over to oppressed residents of Woodstock Nation. Call Warner Brothers and ask them why Fred Hampton is dead and Bobby Seale headed for the electric chair. Ask them why John Sinclair is in jail for 10 years for giving a joint to a longhair nark. Ask them why there are narks in the lobby of the theatre. Ask them why there are new NO SMOKING signs at the entrances to the auditorium, why the ushers cruise up and down the aisles when the film showing is an open invitation to smoke pot and drop acid. Going to Woodstock without being stoned and lighting up at several places in the film makes no more sense than going to White Lake without a stash; but if you believe that the same pigs who are making a shitload of money off of people smoking pot and dropping acid in Woodstock won’t haul your ass off for doing it in the Rhodes, be warned now. Our only solution to this problem is to get so much dope, and so many dope-smokers, into the theatre that they couldn’t stop us even if they wanted to. Hope your high is as good as ours was.

Woodstock is just a movie, but Woodstock belongs to the people.

—miller francis, jr.

NOTE: You may be interested in a little info about those free comps to Woodstock. Warner Brothers gave the Bird 200 passes to a prescreening of the film at the Rhodes Theater, mostly to the afternoon show. They also gave WPLO-FM 500 passes to the night show. Neither knew about the other’s tickets. The Bird figured these passes would be a good way to raise some much-needed cash for the Atlanta community, especially in view of the pig action on 11th Street, so we presented an idea to the Midtown Alliance meeting in Piedmont Park They dug it, everybody else dug it, so on Tuesday the Bird and the Community Center began asking $1.50 donations to the bail fund in return for the Woodstock passes.

Raising the money wasn’t all that easy with 500 free tickets floating around, but if the Bird had known about WPLO’s passes and vice versa, we might have been able to work something out together which would have raised a lot more money. Who knows what WPLO’s reaction to the plan would have been?

The point is that we did raise some money for the bail fund, and Warner Brothers got mad as hell. They called the Bird and asked why we hadn’t asked them about “selling” the tickets, which they considered a crime of the highest degree. Our reply took about 30 minutes, but the gist of it was—it’s none of Warner Brothers’ business. A more relevant question is why didn’t Warner Brothers ask us, and people living in Woodstock communities all over Amerika, what we thought about $3.50 to $6 prices for tickets, none of which goes back to the people who made Woodstock happen in the first place. We’re sure that if Warner Brothers had asked this and similar questions of the kids who know the reality of living in Woodstock Nation, they would have gotten some damn good answers.

-miller francis jr.

Byron Memories

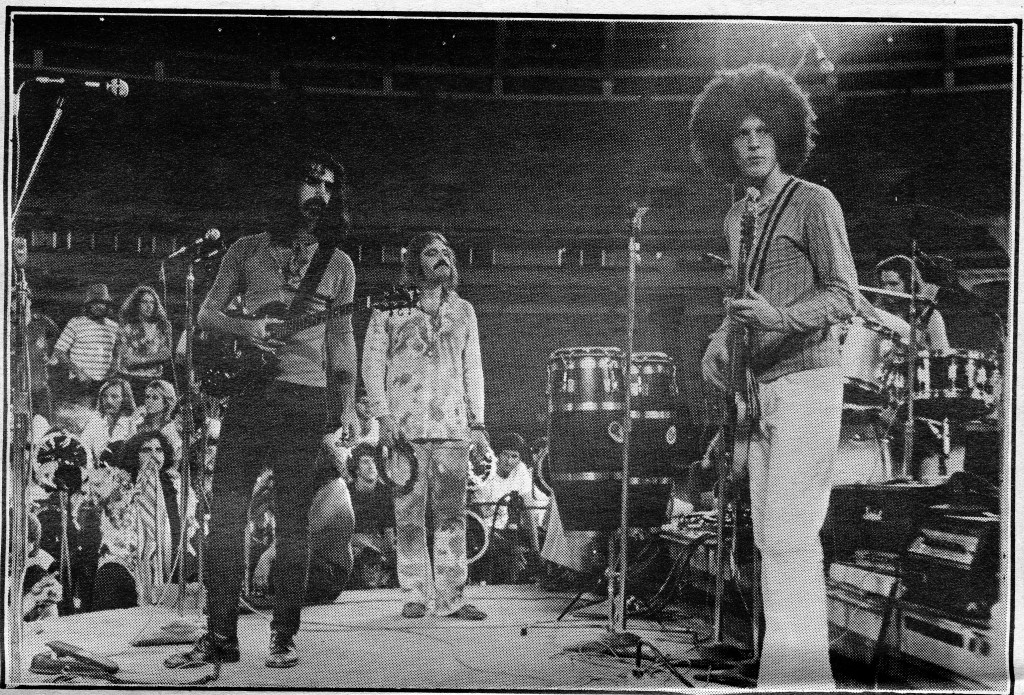

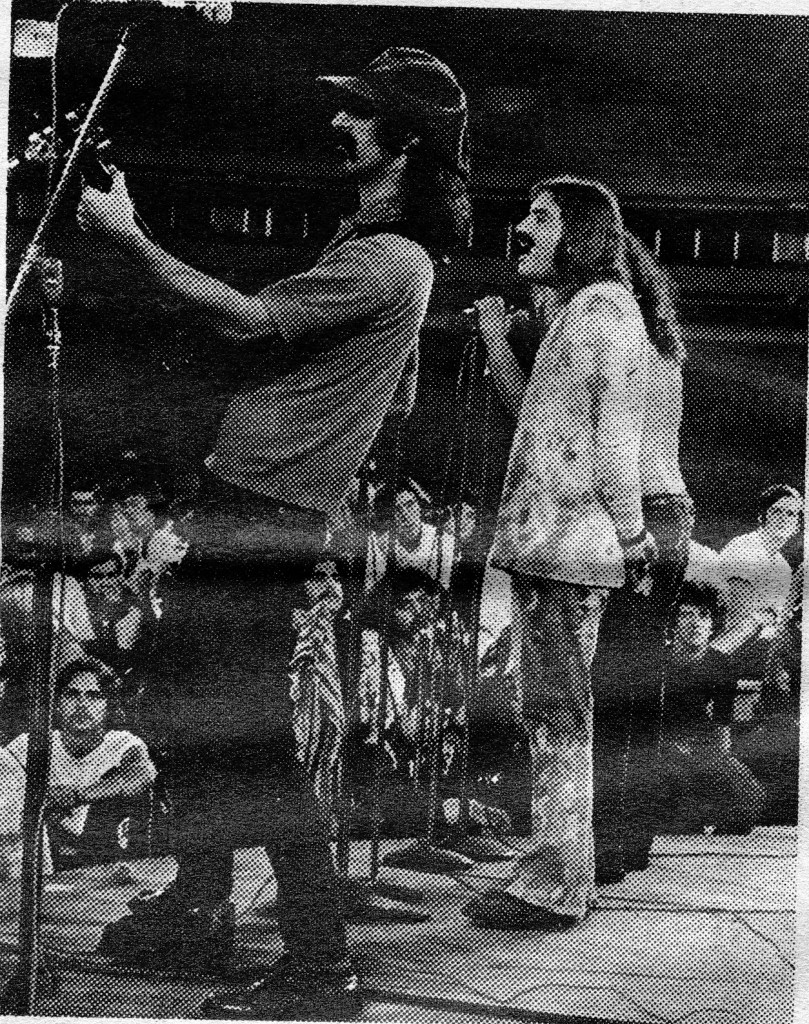

I played at the event, as part of the group “Handle.” We opened the show on Sunday, only a few hours after Jimi Hendrix’s dawn rendition of the Star Spangled Banner has closed the previous night’s festivities. Between the temperature (hot as the hinges of Hell) and the crowd’s having had to sleep in place, no one paid us much attention. However, it has given me a basis to claim that “Jimi Hendrix was my opening act ….”Y’know, Jimi Hendrix was _scheduled_ to hit the stage at 11:00 PM or midnight or something, Friday night, but the schedule had been ruined before noon that day, and just kept getting more and more in arrears. There were groups that weren’t even on the bill. I assume the folks who were running things at the Festival now work for Amtrak.

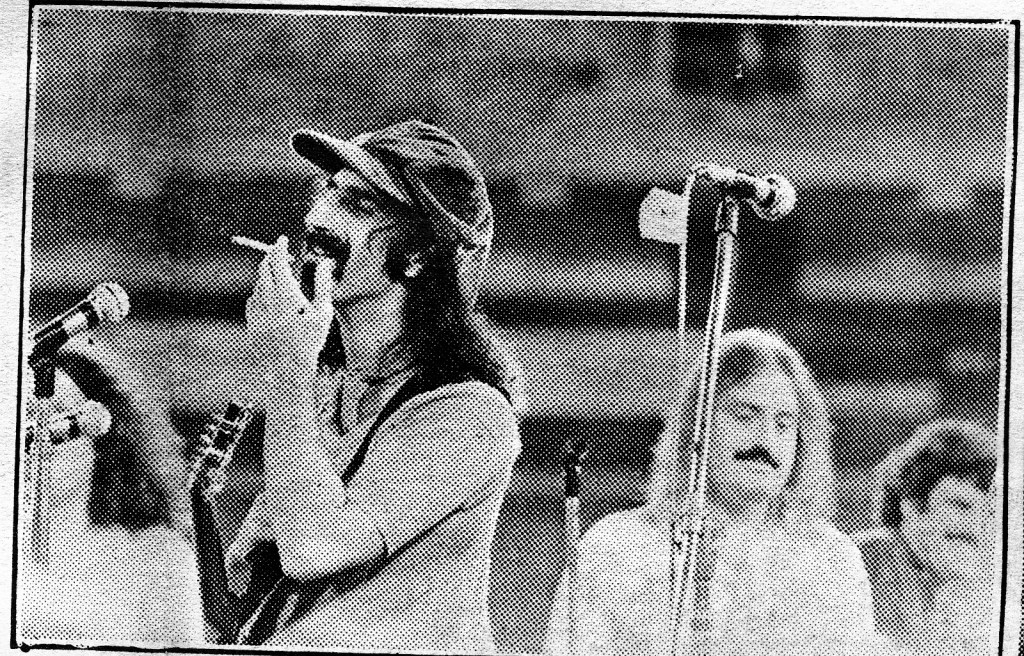

Attached is the only bit of photographic memorabilia I have of the event.That’s me (Shelton Hall) on the right, and Robin Conant on the left. You can barely see the audience in the picture, but I assure you that it was impressive; the stage was about 12 feet high, and from the front of it you couldn’t see the back of the crowd. A vast sea of dirt-caked, bleary-eyed young people.

Attached is the only bit of photographic memorabilia I have of the event.That’s me (Shelton Hall) on the right, and Robin Conant on the left. You can barely see the audience in the picture, but I assure you that it was impressive; the stage was about 12 feet high, and from the front of it you couldn’t see the back of the crowd. A vast sea of dirt-caked, bleary-eyed young people.

Byron Reactionaries

From The Great Speckled Bird July 7, 1970 pg. 4

Now it starts! the pigs are crying don’t let it happen again. The Georgia House Committee on Drug Usage is having hearings on the Byron Festival. They’ve heard from GBI agents who weep and moan about all the drug usage, and God forbid—sex and nudity. Sodom and Gomorrah. Stop it next year.

Of course, the facts are different. As Dr. Hertell, who was in charge of the medical unit points out, Byron, Georgia, was probably the safest place in Amerika on July 4th. Despite the crowd that made Byron the second largest city in the state, there was no major violence, no deaths, and only about thirty persons out of 200 to 400 thousand required hospitalization.

The toilets did overflow. Not enough were on hand and they were’nt emptied during the festival. Occasionally there were temporary shortages of water but they were only temporary.

The medical facilities were incredibly together. There were four major medical facilities staffed by 25 doctors, 30 nurses, and I 2 medical students. Each center was adjacent to an OD (drug overdose) center for bad drug trips. The OD centers were staffed by folks from Atlanta’s Community Center, Homestead Family, and Macon’s HIP program. The center people brought watkie talkies witli them, more were donated and someone from Virginia showed up with a radio-equipped truck that served as communication. Station wagons and buses were turned into ambulances to supplement those hired by the promoters. Patrols with walkie talkies were established to locate problems quickly. At times the OD center overflowed, but everyone got help.

Iin all 6000 to 7000 persons were treated in the medical and OD units. Of these about 40% were for drug problems. Of the drug cases only two or possibly three were really-serious. That during a festival in which thousands were turning on and tripping for the first time.

The togetherness of the medical centers was the result of the determination of Atlanta Community folk and doctors—not the efforts of the festival’s promoters. Before the festival the medical and OD people tried to get a firm commitment from the promoters to ensure good medical services. No go. Then the doctors estimated the cost of adequate medical care—$20,000. Steve Kaplow, the main financial backer of the festival, flipped out. Then a week before the festival another meeting was held, this time with Richard Bryan who was more together about the needs of the festival. The doctors got a commitment for medical supplies, but the doctors had to threaten the promoters with an injunction to stop the festival before they’d agree to supply a helicopter for medical use. That chopper saved at least one life.

Medical plans were made for an anticipated attendance of 80,000 By Saturday morning supplies were running out. Kaplow refused to buy more, saying that people had crashed the gates and he was no longer responsible. Under pressure he bought more from the State Health Department at cost.

It got together anyway. The doctors did have to turn to the Army for a couple of additional helicopters. Some of the ambulances were hassled by the State Police on the way to Macon. One of the overdoses was a really freaked-out 45 year old farmer who on a dare from buddies took acid while walking around the grounds. But it did work-well.

It worked despite problems with the promoters. But it worked not just because of the togetherness of the medical people. It worked because 400,000 functioned together communally, working together, helping each other. Not exactly an All-Amerikan 4th of July.

—gene guerrero.jr.

Hendrix plays Byron

On July 4th, 1970 Jimi Hendrix played The Star Spangled Banner like never before. with Fireworks and heat lightning flashing overhead.

Here is Jimi’s setlist with links to video. Please notify if links vanish.

1.Fire http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AawL5Ntx0RM

2.Lover Man

3.Spanish Castle Magic http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aBxXJBJNjA

4.Red House http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jFk83s8qMKw&mode=related&search=

5.Room Full Of Mirrors

6.Getting My Heart Back Together Again

7.Message To Love

8.All Along The Watchtower http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1oFfeQKnHeQ

9.Freedom

10.Foxey Lady http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_5W4DwZIU0

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hb7ln5vlS_k

11.Purple Haze http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AUekhW5_PEA&mode=related&search=

12.Hey Joe http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixXb6MS660E

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixXb6MS660E&mode=related&search=

13.Voodoo Chile(slight return) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v7yPRYL_Oq0&mode=related&search=

14.Stone Free http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3FBGgZv2l4

15.Star Spangled Banner http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jo-3HB2QdUU

16.Straight Ahead http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jipEHQlOLVQ

17.Hey Baby(Land Of The New Rising Sun)

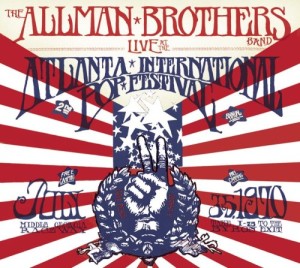

Atlanta [Byron] Pop Festival 1970

Performers included the The Allman Brothers Band, Terry Reid, Spirit, B.B. King, Procol Harum, Jimi Hendrix (just ten weeks before his death),Grand Funk Railroad, Ravi Shankar, 10 Years After, Johnny Winter and John Sebastian.

Bill Mankin’s corrected list of performers.

Click here to read Bill Mankin’s story from pre-festival preparations to afterwards.

On July 4th, 1970 Jimi Hendrix played The Star Spangled Banner like never before. He and the air were electrified. Fireworks and heat lightning flashing overhead in competition. “All Along the Watchtower”. For more on the Hendrix set and videos see:

Hendrix plays Byron Great pictures of Hendrix onstage at Byron

Available at Amazon Kirk West on the CD

The Allman Brothers have released their set on CD. They were not famous enough to be allowed to play at the first Atlanta Pop Festival, then…

There is video The Strip project was honored to have invited a few guests to see of the Allman Brother’s performance at Byron. You can see they know this is their shot at the bigtime. They go on stage a Georgia band and play like their lives depended on it. They were on fire and the astounded audience was stunned, but loving it. Most had never heard electrified Southern blues, and no one played it better than Duane and Dickey’s entwined interplay of screaming notes. They came off the stage stars and the crowd demanded another set later.

Earl McGehee’s Photos on flickr

Were you at The Free Stage? – Carter Tomassi’s has the only photos of which I am aware. It was a long bulldozed trek into the woods. It had sprung up so many dealer’s camped with signs it became nicknamed Acid Alley. Many of the performers played here also. Much more up close and personal. We were unable to loacate its whereabouts in the now built up area. Memories?

We would like to collect your Atlanta stories at this site. Next time you’re deep in meditation about the 1970’s please feel free to send over any stories you remember. We hope to add on memories and pictures from as many people as possible.

Read The Great Speckled Bird’s “What beast is this that crawls to Byron to be born?”

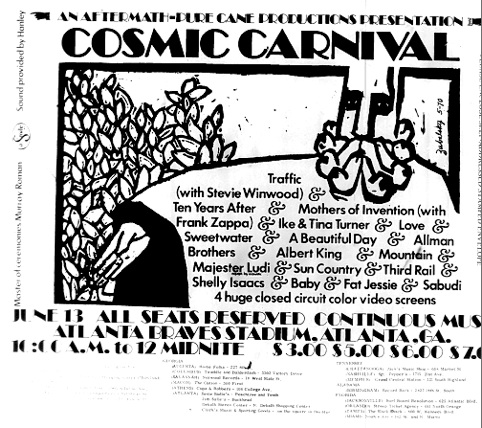

Cosmic Carnival 1970

The Great Speckled Bird Vol 3 #25 pg12, June 22, 1970

Cosmic Carnival 1970

By Miller Francis

Well, folks, we been ripped off. Say it LOUD- the Cosmic Carnival was a gigantic R-I—P-O-F-F! The Bird used to get criticized for being on a “negative trip,” always looking for the worst in any situation. Always rapping on about Capitalism and pigs and a lot of other nasty elements in the Amerikan way of life. So, when the Cosmic Carnival ads began appearing, we took the promoters at their word and printed a “positive” article that stressed the low price, the TV lightshow, the quality of the performers, and the No-Hassle promise of Aftermath/Pure Cane Productions. It’s obvious now that, as usual, the groovy things about the Cosmic Carnival came from Us, the People, and the rip-offs came from Them. Don’t forget that Woodstock was free because we refused to pay for it.

Just walking around inside the Atlanta Braves Stadium, center of Atlanta machismo, the scene was like a free zone liberated by freaks. Dope was everywhere— mescaline, grass, acid-and nobody seemed uptight in the new and strange environs of official city property. Longhair, tie-dyed clothes, skin, love and dope stood out glaringly against the C & S Bank billboard, the giant ads for “the real thing” that let you know who is really running the city of Atlanta. But the only people present were freaks. I suppose that in order to make any money on something as overblown as the Cosmic Carnival, promoters have to use saturation advertising (which they did) to bring in college students and other young people outside the growing freak communities all over the Southeast. But they didn’t come-just Us, crazy, hairy, stoned freaks, the only truly loyal Rock music audience that ever existed in the first place. As it turned out, we were the show. Think about it-besides Frank Zappa, what was the most exciting thing of all other than the sheer joy of turning on in the Atlanta Stadium in the , glare of the C & S and Coca-Cola billboards?

The music was the big rip-off. “It’s a Beautiful Day,” according to the emcee, “made the day beautiful,” but Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention made the day. Evidently the Atlanta/Southeast hips have listened to and loved the music of A Beautiful Day, and everybody grooved on the response the group got, especially violinist Le Flame. Traffic did some good stuff, but as far as this participant is concerned, the volume was so low that most of the music sounded like it was coming from a transistor radio in the next apartment! The Allman Brothers especially suffered from this ridiculously low volume. When the Mothers began, however, a speaker came on that hadn’t been on before, so their set was at least a third louder than anything else. Just in time, too, because the Mothers did a terrific set built around their recorded work, somehow managing to reproduce all the freaky elements that come easy to recording but not so easy to a live performance.

The music was the big rip-off. “It’s a Beautiful Day,” according to the emcee, “made the day beautiful,” but Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention made the day. Evidently the Atlanta/Southeast hips have listened to and loved the music of A Beautiful Day, and everybody grooved on the response the group got, especially violinist Le Flame. Traffic did some good stuff, but as far as this participant is concerned, the volume was so low that most of the music sounded like it was coming from a transistor radio in the next apartment! The Allman Brothers especially suffered from this ridiculously low volume. When the Mothers began, however, a speaker came on that hadn’t been on before, so their set was at least a third louder than anything else. Just in time, too, because the Mothers did a terrific set built around their recorded work, somehow managing to reproduce all the freaky elements that come easy to recording but not so easy to a live performance. Zappa’s charisma was intact, from the time he appeared at various points in the stadium, rapping with kids, to his work on stage/to the long trail of Zappa freaks who followed him from the stage across the field and up the stairs of the bleachers. We heard it all, the satire, the campy reformulations of 50s Rock, the farther-out material inspired by the New Music of Black musicians, all of it blended and intertwined into Zappa compositions that miraculously hold together, performed by one of the most brilliant groups of vocalists and instrumentalists in all of Rock music. Fantastic, and it put the audience through some heavy mind/music changes! (Note: word has it that those two outasight vocalists are lead singers for the Turtles!)

Zappa’s charisma was intact, from the time he appeared at various points in the stadium, rapping with kids, to his work on stage/to the long trail of Zappa freaks who followed him from the stage across the field and up the stairs of the bleachers. We heard it all, the satire, the campy reformulations of 50s Rock, the farther-out material inspired by the New Music of Black musicians, all of it blended and intertwined into Zappa compositions that miraculously hold together, performed by one of the most brilliant groups of vocalists and instrumentalists in all of Rock music. Fantastic, and it put the audience through some heavy mind/music changes! (Note: word has it that those two outasight vocalists are lead singers for the Turtles!)

All the people who bought $7 tickets were in for a shock when they saw the size of the crowd—$3 bought the best seat in the house. That sacred ballfield became more and more a symbol of the stupidity of young people asking, begging, crawling to city officials for OUR OWN MUSIC—it was just a matter of time before we got up off our asses and eliminated the distance between us and the music. It happened during the Allman Brothers set, and rightfully so; they have the sound we love, the sound we needed to say Fuck It to the city of Atlanta. Duane told us to go back to our seats, and we sheepishly did so, but the Cosmic Carnival wasn’t really worth getting busted for. Amerika always looks to “leaders” and “inciters” to pick on whenever they want to come down hard on young people (that’s what the Chicago Conspiracy trial was all about), so don’t be surprised if some Atlanta pig, or group of pigs, decides that the Allman Brothers “incited” us to storm the ball field. If the city pulls this sort of shit, we’re gonna back up the group with everything we’ve got. Get ready because it just might happen. Bongo was busted this weekend because he is a “leader.” What we have to get straight is the fact that our musicians are responsible to us, not to the city of Atlanta, not to those billboards and the trust Mountain do a little bit of their hard and heavy Rock. To no one’s surprise, they did not play in Piedmont Park Sunday. Majester Ludi did play, and while a few people may think it was a big deal that they appeared in the park, we have many local Atlanta bands who can blow Majester Ludi off the stage—they. were obviously on a New York snob trip the whole time they were here, and all they play is what will get them on a record and nice PR photos in Billboard magazine, etc. What a hype! Herman Hesse should turn over in his grave.

All the people who bought $7 tickets were in for a shock when they saw the size of the crowd—$3 bought the best seat in the house. That sacred ballfield became more and more a symbol of the stupidity of young people asking, begging, crawling to city officials for OUR OWN MUSIC—it was just a matter of time before we got up off our asses and eliminated the distance between us and the music. It happened during the Allman Brothers set, and rightfully so; they have the sound we love, the sound we needed to say Fuck It to the city of Atlanta. Duane told us to go back to our seats, and we sheepishly did so, but the Cosmic Carnival wasn’t really worth getting busted for. Amerika always looks to “leaders” and “inciters” to pick on whenever they want to come down hard on young people (that’s what the Chicago Conspiracy trial was all about), so don’t be surprised if some Atlanta pig, or group of pigs, decides that the Allman Brothers “incited” us to storm the ball field. If the city pulls this sort of shit, we’re gonna back up the group with everything we’ve got. Get ready because it just might happen. Bongo was busted this weekend because he is a “leader.” What we have to get straight is the fact that our musicians are responsible to us, not to the city of Atlanta, not to those billboards and the trust Mountain do a little bit of their hard and heavy Rock. To no one’s surprise, they did not play in Piedmont Park Sunday. Majester Ludi did play, and while a few people may think it was a big deal that they appeared in the park, we have many local Atlanta bands who can blow Majester Ludi off the stage—they. were obviously on a New York snob trip the whole time they were here, and all they play is what will get them on a record and nice PR photos in Billboard magazine, etc. What a hype! Herman Hesse should turn over in his grave.

God bless the Allman Brothers. The jam, with pieces from A Beautiful Day and an unknown harmonica player, was really fine. But please, somebody, turn the volume up—we don’t just want to hear it, we want to feel it, too! Steve Cole is doing a lot for Rock & Roll in Atlanta (without ripping us off), but some of the shit he was putting down in the park about “violence,” etc. was either misdirected or mistakenly handled. What he was talking about was the kind of stuff that occurs within various elements of our community, but he didn’t make that clear enough. We must learn that any problems and hassles we have within our community—”Contradictions Among the People,” as Mao calls them—must tees, corporate liberals, and Massell’s behind them. When the shit comes down on them, it comes down on us.

God bless the Allman Brothers. The jam, with pieces from A Beautiful Day and an unknown harmonica player, was really fine. But please, somebody, turn the volume up—we don’t just want to hear it, we want to feel it, too! Steve Cole is doing a lot for Rock & Roll in Atlanta (without ripping us off), but some of the shit he was putting down in the park about “violence,” etc. was either misdirected or mistakenly handled. What he was talking about was the kind of stuff that occurs within various elements of our community, but he didn’t make that clear enough. We must learn that any problems and hassles we have within our community—”Contradictions Among the People,” as Mao calls them—must tees, corporate liberals, and Massell’s behind them. When the shit comes down on them, it comes down on us.

Hope everyone dug the four giant TV screens and the different angles they gave of the music on stage! Actually the only angle the promised “lightshow” gave was another glimpse at the way Rock promoters are allowed to get away with murder, without accounting to anybody, least of all the people who make it possible for Rock music to exist in the first place.

Funny thing about all the music promised, too. It weren’t there! Love, Sweetwater, Albert King and Ten Years After did not play, and all but Love were there, at the Stadium!

Worst of all, Ike & Tina Turner, one of the most awaited of all the scheduled groups, didn’t get to play at all. Incidentally, there’s something fishy about the lineup anyway. If it’s true that the Cosmic Carnival had a 12 o’clock curfew to meet (that’s what they say, that’s why the thing ended when it did), then why does the official schedule have Ike & Tina Turner coming on at midnight? There’s no way under the sun that that schedule could possibly have been met (have you ever known stagehands and technicians who weren’t stoned during a show?), so how come so many groups were signed up (if they really were) to play in such a short lime? What an insult to have to listen to Shelly Isaacs when you came to hear Albert King and Ike and Tina Turner!

And that sound by Hanley—whose idea was it to keep the volume low? Hanley’s? Aftermath/Pure Cane’s? Sam Massell’s? Mills B. Lane’s? Coca-Cola’s? C&S Bank’s? Or, more probably, a sick combination of all of these. Did anybody ask YOU how loud you wanted the sound to be, because I wanted it loud enough to clean our heads out, and for ten hours, I heard fellow freaks yelling “louder! LOUDER!!!” and I don’t remember anybody from the stage answering that rather clear demand. Can you imagine what will happen to our music if we let ourselves be intimidated by pigs who don’t know Frank Zappa from Patti Page, and if we allow ourselves to be forced to listen to our music at low volume? In the words of Tommy, “We’re not gonna take it/Never did and never will!”

And that sound by Hanley—whose idea was it to keep the volume low? Hanley’s? Aftermath/Pure Cane’s? Sam Massell’s? Mills B. Lane’s? Coca-Cola’s? C&S Bank’s? Or, more probably, a sick combination of all of these. Did anybody ask YOU how loud you wanted the sound to be, because I wanted it loud enough to clean our heads out, and for ten hours, I heard fellow freaks yelling “louder! LOUDER!!!” and I don’t remember anybody from the stage answering that rather clear demand. Can you imagine what will happen to our music if we let ourselves be intimidated by pigs who don’t know Frank Zappa from Patti Page, and if we allow ourselves to be forced to listen to our music at low volume? In the words of Tommy, “We’re not gonna take it/Never did and never will!”

We dug the final rush onto the ballfield to hear be dealt with within the community, not by outside forces and certainly NOT BY THE PIGS! We have our own Street Patrol-STP means “Stop the Pig”/”Serve the People”—and we must rely on them to settle our disputes. Otherwise, the pigs are going to step in, and we’ll all be the worse for it.

The Rock music scene in Atlanta is really fucked up. It may be dying. But remember that Rock music has always been defined as an industry, subject to all the forms and limitations of capitalism—promoters, middle men, expensive tickets, deals with the city, etc. It’s becoming increasingly obvious that this capitalist base has to go, or the music has to go—1 don’t know about you, but I’m not ready to give up my music. Let’s have it because we demand it, not because the city lets us have it. It isn’t theirs to give.

One thing: Don’t let anybody divide us up into Good and Bad. We—all of us—are one community. If there are problems, WE can solve them. Beware of anyone who tries to divide us into “violent” and “peaceful” elements. These are the kind of people who always put down “violent protest” by us, and don’t get uptight ahout what Martin Luther King, apostle of militant (dig it!) nonviolence, called “the greatest purveyor of vio- lence in the world today”—the United States government. The brother who gets sick at his stomach at the shit the pigs pull on the strip is not alone when he throws a rock, or calls a pig a pig. The sister who fights back, doing what she has to do to survive, must have our support. Brothers and sisters who organize to Stop the Pig are working in our interest. I don’t know anybody who is planning to leave Atlanta just because Massell and his henchmen don’t want the hip community to run itself and make its own decisions, and it would be outasight is all that new blood Massell is worrying about would get it on and come right on into Atlanta. Welcome, brothers and sisters! We dig Atlanta and our scene here, and if you want to turn on to it, we’ll make a space in the lives that we’ve planned. The Atlanta Chamber of Commerce spends a fortune each year trying to encourage businesses, industry and white collar executives to move to Atlanta; now it says it wants to discourage young people from turning on to one of the best scenes in the whole country. It’s not up to Massell and it’s not up to Coca-Cola. Power to the People!!!

—miller francis, jr.

Woodstock 1969

Woodstock had connections to many Atlantans both in helping stage the event and as performers and attendees. Many people traveled from Atlanta’s festival to Woodstock. After the film was enjoyed by so many, behavior at a rock festival acquired a standard as The Woodstock Nation.

Woodstock had connections to many Atlantans both in helping stage the event and as performers and attendees. Many people traveled from Atlanta’s festival to Woodstock. After the film was enjoyed by so many, behavior at a rock festival acquired a standard as The Woodstock Nation.

The Producer of Woodstock talks

Woodstock-Generation Secrets Most People Seem to Have Forgotten