Phillip Rauls’ Photo essay

“THE ATLANTA POP FESTIVAL’S 40th ANNIVERSARY”

Phillip Rauls’ Photo essay

“THE ATLANTA POP FESTIVAL’S 40th ANNIVERSARY”

Read Atlanta newspaper’s accounts (links inactive during translation)

AJC July 1 ‘Rock It to All’ Festival Theme

AJC July 4 Joplin, 80,000 Rock Buffs To Make Festival Scene

AJC July 5 That Sound’s Really Cool, Man, But It’s Mighty Hot

ACon July 5 Music Fans Stay Orderly Despite Heat, Wine, Drugs

AJC July 7 Pop’s The Thing Despite Heat at Hampton

AJC July 7 Pop Group Came To Find a Groove

ACon July 12 A Lot Happened at Pop Festival

July 7, 1969 The Grateful Dead in Piedmont Park

Download The Dead in Piedmont Park

AJC 7/8/69 Bonnie says she is a natural, clean hippie

AJC Magazine July 12 Park Rock Concert Wows ‘Em

Aug 20,1969 Metro Beat Magazine Pop Festival

Printed from the Joni Mitchell Discussion List website.

http://www.jmdl.com/articles/view.cfm?id=824

On December 28-30, 1968, Gulfstream hosted the Miami Pop Festival, post-Monterey and pre-Woodstock. The festival drew 100,000 fans over three beautiful winter days, and featured many seminal acts of the time: The Grateful Dead (Free download http://www.archive.org/details/gd68-12-29.sbd.cotsman.5425.sbeok.shnf),

Chuck Berry,

Marvin Gaye, Joni Mitchell, Richie Havens, Steppenwolf, Procol Harum, Country Joe and the Fish, Canned Heat, the Turtles, and Three Dog Night were among the fourteen daily acts that appeared on two stages — one at the grandstand and the other near the south end of the park — for the price of seven dollars per day.

According to Rolling Stone (February 1, 1969), the festival was “a monumental success in almost every aspect, the first significant — and truly festive — international pop festival held on the East Coast.” Woodstock, of course, took place in 1969, and Hallandale city officials, horrified by visions of stoned hippies dancing naked at Gulfstream, nixed plans for a second Miami Pop Festival.

The Miami Festival: An Inspired Bag of Pop

by Ellen Sander

New York Times January 12, 1969 ————————————————————————

The area was alive with beads, bells, prim and pressed cotton resort wear, cheerful faces, spontaneous dancers, and a total of 99,000 fans. They had all come over a three-day period from the Eastern Seaboard, from Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, and as far away as Montreal and Big Sur to attend the first annual Miami Pop Festival held in Gulf Stream Park, Hallandale, Florida, from one to ten P.M. each day, December 28 through December 30, 1968.

The event was a resounding success in both organization and programming, making it the first significant major pop festival held on the East Coast and the first successful pop festival since the now legendary Monterey International Pop Festival in June, 1967.

The program, which consisted of 35 acts, offered hardcore blues, sassy San Francisco funk, rockabilly, gospel, rousing rhythm and blues, folk music, jazz, top 40 pop, Latin rock, and hillbilly music in addition to a solid lineup of rock and roll. The generous expanse of pop was with a conscious sense of scope, history, roots, and direction.

With a singular lack of superstars, the festival was the first event of its kind to successfully showcase pop in perspective, gracefully carrying the hillbilly-and-grits banjo picking of Flatt and Scruggs, the multi-textured outbursts of the Grateful Dead, the Chicago blues of the Paul Butterfield and the James Cotton Blues Bands, the jazz of the Charles Lloyd Quintet and the hard rock of Steppenwolf, all on the same bill.

The 35 acts gave a total of 42 performances on two stages during the three days. Concerts were staggered in sets of 45 minutes each with a 15-minute overlap, making it possible to see everything or stay in one area for those portions of the program which seemed most attractive.

The two performance areas, one in front of the Gulf Stream race track grandstand, another in a large tree-lined meadow, were several acres apart. Between the two were an art exhibit, arts and crafts concessions, enormous pop art sculptures, food and drink concessions, and two live, painted Indian elephants who watched the spectacle with politely amused ponderousness. The layout of the grounds and situation of the diversions kept the crowd in a constant state of flux, and the entire affair had a continuing, organic feel about it, being both artistic and entertaining at each meandering turn. The weather was balmy, audience and performers were in good spirits, and there was hardly a set that didn’t meet with wild enthusiasm.

Particularly satisfying were Three Dogs (sic) Night, a brilliantly eclectic group that did inspired re- creations of, and improvisations around the hits of other pop artists and contemporary writers; and also Pacific Gas and Electric, a blues-rock-gospel ensemble in spirited, uncontrived, crisp music. Their audiences, for the most part, had never seen them before. These two and Sweetwater, a Los Angeles group with a vaguely oriental rock sound, are among the best and most underexposed talent in the country. The Festival was a perfect setting for the discovery, rediscovery and elevation of fresh sounds in the musty closet of rock.

Chuck Berry who, along with Elvis, precipitated the onslaught of rock way back in the fifties, performed a chronological set of his old hits, which by now are institutions. Marvin Gaye, Junior Walker and the All Stars, and the Sweet Inspirations burrowed deep into the rich black roots of rhythm and blues, the basis of all rock and roll. Richie Havens did unique, incandescent thing. From England, Procul Harum and the Terry Reid group performed. Country Joe and the Fish, which temporarily includes Jack Cassidy on leave from the Jefferson Airplane, played a set. It was a hardy, inspired mix of sounds.

Significantly enough, the only real disappointment was Steppenwolf, which came on in all arrogance and superstar nonchalance for one of the Sunday night’s closing performances. They were one of the biggest names scheduled and the worst show. Also Fleetwood Mac, a blues- inspired group from England, had a hard time getting together musically. Folk duo Ian and Silvia were rather restrained at their first pop festival. And the Box Tops gave off a feeling of irrelevance. But these failures were somehow bearable.

Constant magic and music filled the air as crowds wandered comfortably from area to area. There were several narcotics busts made on the festival grounds but no violence or brutaility (sic) of any kind ever erupted. The police, private security corps and concessionaires were easygoing and goodnatured and, as festival producer Tom Rounds observed dryly Monday evening when two pot smokers were quietly escorted into paddy wagons “Anyone who can’t find a place to turn on in 250 acres without getting caught, is just dumb.”

The Miami Pop Festival was a monument to pop, an excellent model for future events of this kind. It was a shift in perspective, an experiment in depth rather than sensation. It had that special balance of humility and extravagance which consistently delighted an initially skeptical audience. After all, these pop fans had been through a year and a half of badly produced, expensive pop festivals, most of which failed miserably. The ticket price was only $7 for ten consecutive hours of entertainment each day.

Jose Feliciano appeared twice, Joni Mitchell closed her notably lovely set singing Dino Valenti’s “Get Together,” accompanied by Richie Havens and Graham Nash, late of the Hollies. Fred Neil, an oft-forgotten folk singer and songwriter who directly or indirectly influenced a good portion of today’s pop, visited the festivities Monday night looking lean, tanned and healthy. Music from both stages could be heard all over the festival grounds and spontaneous jams ignited in the performer’s private area.

Post-festival celebrations included a rock and roll wedding in which Spanky of Spanky and Our Gang was married to Medicine Charlie of the Turtles in a folk coffee house in Coral Gables. The wedding party included members of Our Gang, the Turtles, Richie Havens and Tiny Tim. After all that, New Year’s was a letdown.

(c) 1998 Patrick Edmondson (Excerpted from a longer work in progress)

After High School graduation, Gabi had moved to Atlanta to start Georgia State just as Fred was planning to do while living with his benefactors, Uncle Paul and Aunt Evalene. Gabi’s sister, Pixie, had an apartment off North Peachtree so she didn’t have to look for apartments for rent. I was going to be nearby at Oxford, a small country town east of Atlanta, in the fall.

Pixie realized that with Gabi came me, her boyfriend. Pixie drove her light blue Dodge dart down to Oxford almost every weekend to get me for her sister Gabi, then drove us back on Sunday night. Often we gave rides to other weirdoes I was meeting at Oxford. Pixie didn’t suspect that she had become a stop on the hitchhiker’s trail through Oxford.

We had become friends with Dan del Vecchio at Oxford. His brother Jeff had hitchhiked down to visit him. Dan and Jeff are both skinny. Jeff is tall; Dan is medium like me. Dan wears an old-fashioned tuxedo coat with split tails. Jeff has wide glasses and was just out of the Navy and still wore navy bells. They both went to Atlanta and of course came by Pixie’s. Jeff Del Vecchio came by one Sunday and seemed to really tickle Pixie’s fancy, which was great as she had been so down for so long.

December 1968 I had finished one quarter of Oxford and returned home to scandalize Tifton and my father. Gabi of course came with me. We, also of course, came prepared to turn on our old high school buddies and spread the enlightenment.

Meanwhile Pixie had to move, but would not look for a place. Then she called for Gabi and me to come help her move. We came up and went through want ads and called at pay phones and drove around. Finally she found a place in Decatur. Some poor old lady had split off the up stairs of her house on Adams Street, but never knew what was up when she rented to Pixie, her mother and Gabi. A hint should have been when everything besides furniture was just carried in big sheet bundles.

I had to get the family car home for Christmas. We had been talked out of sending for tickets to the Monterey Pop Festival the previous June, so when our Oxford friend Jan Jackson had heard about a similar music festival in Miami at Christmas and had volunteered her boyfriend from UGA, Martin’s VW bus as transportation, we mailed off for four tickets. The day after Christmas, Martin, Jan, and Gabi were to drive to Tifton to pick me up for the trip to Miami in Ol’ Baby, the faithful blue VW bus into which Martin had built a double decker bed.

My parents and siblings were very curious when Ol’ Baby pulled into the carport and Gabi and this couple got out. I was surprised to see Jeff DelVecchio and another guy, Mike Smith, also climb out. Seems they had heard of the festival and being inveterate hitchhikers had headed to Atlanta. They surprised Mrs. Ujhelyi when they came knocking at Adams Street late at night. Now they were in the mix and Jan also had promised a woman from Oxford we’d stop by Leesburg, Fla. and pick her up to go to Miami.

Thus was our merry band to be. Later we would be joined by a woman from Miami Mike had planned to see. She ran away, sort-of, to go with us. Later they got married and came to Atlanta to honeymoon at a big hotel and called Gabi and I to “get stoned and fuck up the plot of Streets of San Francisco on this big color TV with us to celebrate”. We’d already fucked in sleeping bags beside each other in the Indian Reservation dump; kinda creates a special bond.

Almost as soon as we pulled out of our driveway Martin asked Jeff,” Where did you hide that acid?”

“Up here in the light. All the grass is in the toolbox.” He answered from the top bunk. After this exchange I was aware I was leaving Kansas.

We were passing around a joint as we headed down I-75 at a steady purring 55 – 60 mph. Gabi and I took turn chattering like magpies, stoned ones at that, in the bottom bunk. We had been apart for a few days so had lots of information to exchange. We were almost two receptors of the same brain it seemed at times.

The radio stations came and went. It rained and the windshield wiper on the passenger side stopped. Martin told Jeff to bang on it. He did until he broke the windshield, which annoyed Martin a bit. I had brought Rolling Stone. I had subscribed and got my copy early. It was on groupies. I believe we all read it cover to cover over the trip since it was the only reading material we had.

Finally we turned off to pick up Laura. Her suburban parents eyes were filled with horror at the thoughts of her getting in that bus even with Gabi and Jan, but they were polite. I do believe she inhabited both Jeff and Mike’s sleeping bags before we returned her home.

We drove into Miami and called some friends of someone. They directed us to meet them at Coconut Grove which was full of hip shops and people. Stopped to see Michael Lange, who someone knew, at his head shop. We bought a leather headband and bag he had made. He later ran another festival in Miami then the Woodstock festival.

We sat in the sun under palm trees and watched the people flow. Later we worked our way back to a campground nearer the festival spot. The people were very wary of our crew checking in to a family campground. Little did they know of the collecting invasion forces.

Awoke, used showers and went searching for a Huddle House for breakfast. Martin has high metabolism and must eat regularly. Then we went and got high to await the start. We then waited outside the racetrack at Hialeah for the gates to open. Martin starts talking to a man by a van. He is a professional photographer and gets to drive his van of cameras inside. He invites us all for the ride. We saw him all through the festival and saw pictures we’d seen him take in Rolling Stone. We were quite impressed.

The festival began at 1PM and lasted until 10PM each day for three days. Saturday December 28th Jose Feliciano, Procol Harum, Buffy Sainte Marie, Country Joe and the Fish, Three Dog Night, Chuck Berry, The Infinite McCoys, Booker T and the MGs, Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green, Pacific Gas and Electric, The Blues Image.

Some acts performed more than one day. Also some brand new groups were slotted in as The Amboy Dukes with Ted Nugent still an acidized hippie in tight velvet pants. The ads said “a thousand wonders and a three day collage of Beautiful music”. That was an understatement. There was a stage on the racetrack with all the seats then another stage way out in the parking lot. You could walk from one and be at the back or plan ahead and be right at front for special acts.

Art works from the Coconut Grove art school had been strategically placed throughout the grounds. Tripping people were constantly discovering them and getting hung up in examining the art and never leaving its tiny alcove in the hedges for hours.

There were milk cartons like kids use at school, except made of plywood and so big the mouth is a full size door entrance. We were walking one time and saw a group of people collected around one and we could hear music. Joni Mitchell and Jimi Hendrix were playing acoustic guitars and harmonizing. Duane Allman, then unknown except to Georgians, watched from the crowd.

When Joni later performed at the fest Hollies singer-songwriter Graham Nash, whom Joni had met through their mutual friend, David Crosby, accompanied her. Joni’s account

But we were in a hurry to see County Joe and the Fish, of whom we were big fans, for the first time.

Later we found out Hendrix was involved in the financing of this festival and held one of his own at this raceway later in the spring of 1969. His other partners in putting on this one got emboldened by the great success and started planning one at home in New York state where they were from. They later did it as Woodstock.

Also Duane Hanson http://arted.osu.edu/160/18_Hanson.php had his realistic looking people in unusual places to be found. Once I’m stumbling along with the crowd which parts and leaves me hanging over the most realistic bloody motorcycle wreck!

Then there were the stereotypical old tourist couple standing and pointing out something.

Most performers hung around the grounds and enjoyed themselves as long as they could stay. Other famous people had just come to experience the east coast Monterey.

We realized the campgrounds would probably be filled or closed by the time the crowd exited for the night. We asked around and heard the Indians were coming to the rescue of their brothers the hippies.

Yeah, and scalp them! The Seminoles motioned the line of campers with signs, “camp cheap. This Way.” with an arrow. We should have learned to beware American Indians bearing arrows.

We followed in the dark out into areas looking swamp even in the darkness. Then a campground, but the arrows sent us further. Phantasmagoric sights to exhausted people. Finally. You can stop. Sleeping bags plopped and people were asleep on hitting the ground.

Upon awakening in the morning we found ourselves in the dump for the reservation campground. A garbage filled swamp surrounded this tiny isthmus full of cars. Lots of bugs and we heard gators grunting in the bushes around the water. They would only allow hippies access to a standpipe for water, so no shower. Also wouldn’t allow access to the laundry. Why are hippies so dirty?

Jeff’s experience in naval matters had him direct us to a big marina. We hung outside the clubhouse until we saw a hip looking kid. He let us in and lent us his key so we could get in both genders for showers and hair washing. He left telling us which boat, yacht actually, to return the key. It felt good to wash off the Seminole dump. We were a clean but scraggly still collection of beatniks.

When we returned the key, the kid’s father came out and we thought he would be mad, but he invited us aboard and kept filling a pipe of high quality hash to smoke before we left. Wow, is this world changing or what. We hurried to eat ravenously. Everything, even salt crystals were exquisite in their tastes and textures. As hunger slacked everyone went from wolf to aesthetes enjoying the very essence of the act of eating. And we had a Pop Festival to go yet today!

Sunday December 29th Steppenwolf, Marvin Gaye, Grateful Dead, Hugh Masekela, Flatt and Scruggs, Butterfield Blues Band, Joni Mitchell, James Cotton Blues Band, Richie Havens, The Boxtops.

The second night we would not fall victim to Seminole arrows. We went to look for the girl Other Jeff knew. He called and she told us to come quietly. We drove stealthily into the Miami suburbs and cut the engine to drift into the driveway of a split-level suburban manse with a large lawn. Again exhausted sleeping bags deployed.

We awoke to the sun and a small girl walking around looking at us. She ran back into the house and we scrambled to collect ourselves back into Ol’ Baby to make a get away. Before we were successful, the girl returned. “Mama wants to know how many of you want eggs?”

Mom invited us inside and made a big spread. Biscuits, honey, orange juice, eggs, ham, lots of coffee. It was like being home something my mother would do. “Invite your freaky friends in dear and introduce them!” Mom even made sandwiches she put in a pack and handed the women in the group before sending us all off to the festival.

But first we had to make a stop for her teenage daughter to pick up a sack of acid for she and Other Jeff to sell today. I had never knowingly been around tripping people or certainly so many varied drugs, but still Gabi and I were fine with Cannabis forms alone since we didn’t even drink.

Monday December 30th Iron Butterfly The Turtles, Canned Heat, The Grassroots, Jr. Walker and the All Stars, Ian and Sylvia, Charles Lloyd Quartet, Sweet Inspirations, Sweetwater, The Joe Tex Revue.

The Grateful Dead Miami set (Free download

http://www.archive.org/details/gd68-12-29.sbd.cotsman.5425.sbeok.shnf),

The Great Speckled Bird Vol 2, # oct 27, 1969

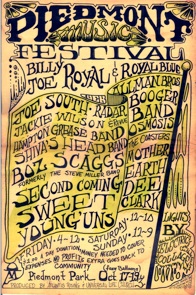

FRIDAY AFTERNOON was almost frightening all those big names, the abruptness of the pop festival’s appearance, the overall speculative nature of this ambitious musical venture and when we got over to the park, there was only a small crowd and some folk singer type running through a Dylan (new) imitation of “Lay Lady Lay.” The portable toilets on the ball field looked desolate in their isolation. Nothing looked good about the scene, and Frank Hughes of the Electric Collage light show was saying over and over, “Everybody’s wrecked!”

Then, miraculously, it happened. The Allman Brothers appeared on stage and began their set a familiar set of blues pieces, long, hard improvisations worked on a tight rhythmic foundation. “I’m Gonna Move To The Outskirts Of Town,” Donovan’s “There Is A Mountain,” one from their new album on Atco which might be called “I Feel Like I’m Dyin’,” some fantastic slide guitar from Duane Aliman on an excel lent arrangement of “Statesboro Blues,” and much more. One of the best exponents of where young pop music is at today, the Allman Brothers got the audience moving and initiated the festival atmosphere that had been absent up until that time.

The crowd was still small by sundown, but it was grooving and becoming larger all the time. We had just begun to realize that the night would be quite cold, but the idea of a pop festival in winter weather seemed oddly appealing (for once a tightly packed audience made some sense). The hippie/freak audience was there, a few straights, some familiar community winos, plus many, many new faces. One short fat fannie dug the music and the people; she thrust her dancing figure up front whenever possible and moved in and around the crowd with a beautiful smile on her face. A wonderful old wino with the face of a leprechaun put down his weather beaten suitcase and umbrella and asked her to dance with him, proceeding to demonstrate his own talents in a Wonderlandish dervish. Soon, everyone was in good spirits.

The band that followed included The Second Coming guitarist from Florida, plus the brilliant, beautiful bass work of John Ivey, and vocals and harp by Atlanta’s Wayne Lackidisi. The lead guitarist was into an erotic contortion bit (he turned in a better performance Sunday), and while Lackidisi’s screaming vocals sum up what is either the best or “the worst of white blues singing (depending on whether you like it or not), some of his harmonica contributions were exciting indeed.

The performance by Joe South in Piedmont Park should have been a major musical event; instead it was a fiasco. South appeared on stage with a trio of accompanists that looked like a Southern Velvet Underground (the suit South was wearing looked like silver velvet). There was an immediate reaction from the audience, one of suspiciousness and distaste from some, amusement from others. To say that a threat to the communal spirit did not exist for a moment would be a lie. South does not relate to the immediate experience of the Atlanta left/hip community in the same way that, for example, the Hampton Grease Band does, and the shiny, luxuriant exterior of the studio talent was perhaps too much in evidence, and with no conditioning for the audience. At the same time, Joe South is unquestionably one of the finest songwriters in all of pop music. We don’t think of him as a performer (though he is a brilliant one), but we are all familiar with his songs through the Top 40. Teenybopper purists who label his three minute pop songs “commercial” and relate to the twenty minute blues extravaganzas of the Allman Brothers as anything other than commercial simply create a false dichotomy between a business oriented around 45 rpm singles and a business built on the 33 1 /3 rpm album. Joe South and the Allman Brothers are merely extensions of the same pop music experience, and they both make some fantastic music in their own areas.

Unfortunately, the sound system was fucked up throughout South’s entire set, and in the middle of one song, the power cut off altogether. South’s excellent vocal style was lost, some of the best lyrics ever to come out of modern country could hardly be heard, and what could have been some exciting guitar work by South was wasted on electronic distortion and noise. South was trying his best to get through “Hush,” “Redneck” (on the new Pacific Gas & Electric album), “Don’t You Wanna Go Home?” a hymn to the Atlanta community called “Gabriel,” and one of the best pop songs ever “Games People Play.” Aside from some attempts at humor that were often misdirected, a female vocalist whose raucous, out of tune shouting al most ruined what little music the South group managed to force through the faulty sound system, and a certain lack of acceptance from some in the crowd, it was good to hear this musical genius in our own park, and it is hoped that the event can happen again under better circumstances.

Considering the formidable musical achievements of Joe South, his last words “Thanks for putting up with us” seemed incredibly ironic. At this time in our development of a youth culture, we need all the bridges we can get, and Joe South may very well be the most important bridge between white country music and black blues and pop that we have. Certainly if one listens to his album Intercept, he will get one of the most all inclusive statements of the Southern hip youth experience available anywhere.

Mother Earth followed South, and again the sound hassles seemed insurmountable. Tracy Nelson was there guzzling bourbon and turning what were probably exciting vocals on “Wait,” “You Win Again,” and a couple of others. She didn’t sing often enough for me in any of the sets in which Mother Earth performed. Boz Scaggs, an excellent guitarist but a largely uninspired vocalist, did some bluesy numbers and an “I Shall Be Released” that didn’t stir up anybody too much. The bassist was featured on a song that he wrote, and the pianist/ organist was the dominant voice on the closing number by Bobby Blue Bland. All in all not very heavy, but the things they did on Saturday with a functioning sound system were a more accurate demonstration of how good this band can be.

Frank Hughes’ Electric Collage light show, one of the finest anywhere, was in operation during the ill-fated Joe South performance, and even though the temperature went way down into the forties, people were grooving, and the loud applause that followed South’s exit from the stage showed that we were prepared to be patient and understanding while the hassles were being worked out.

Dope was everywhere. Various people made announcements (including some absurd compliments on our “peacefulness”), pleas for donations of $1, and at one point Robin Conant asked if we wanted a ballroom in Atlanta. Friday was filled with intimations that much more is going on at these musical events than can be confined within the boundaries

Of Piedmont Park. One hell of a lot of work was put into this park music festival; a lot of people deserve a lot of credit; and just as in the past, the community must support the developing music scene in Atlanta by its involvement. Whether we have a music of community, or end up as merely another link in a capitalist chain of “music” entrepreneurs is up to us.

-miller francisJr.

Saturday

Once more into the tentative temple of Atlanta Aquarians, to the ritual womb of the New Age, to get together, to let our music pour over and through us, hopefully like bonding cement same thing churches sometimes still pretend to be about to weld a communist whole, energized to sustain the struggle to smash the atomizing force working to pry us apart. To dig, that is, some music with the Family.

Crystal-blue day, throbbing (not baking) warmth, folks lolling around on the grass. Hand Band just finishing up (“Apologize for doing other people’s stuff, but it’s a fine tune.” Right on.) Comes now from Macon, GA, the Boogie Chillun, setting up their paste-on flower bedecked drums, testing their l-2s, then Thh-wanng! Into their opening/warm-up number like they knew what they were doing. They did. (Their bass man too far into it to perform “intelligently” he just let his fingers follow the rest of his body, which made the axe a supportive appendage of his total investment in his music. Fine.) Much excited appreciation of their vocalist’s copy of Led Zeppelin’s “I Can’t Quit You, Baby.” A copy is a copy, but Boogie Chillun‘s a young band, still putting it together, still, I felt, trying to “prove” something, still “performing” “for” an “audience,” instead of working with us to get off a tribal celebration. But. That’s how bands grow together.

Like Lee Moses. Four black bluesmen who both presented and built upon that genre. Lee Moses on lead guided all of us on a guided tour of the mysteries of the guitar, excitement modulator: advancing and retarding the frenzy building across the grass, until one incendiary riff jerked us to our feet, there to remain until the set concluded, we reluctant, but also relieved from concentration of energy that might have spilled us over our permit-bordered reservation (that’s a no-no). Nor was Lee Moses THE show never having seen the group before, we were several minutes into the set before I knew for sure who Lee Moses was one sign of a together group. Because the denimmed rhythm man toured his own force with a rendition of Tony Bennett’s classic (just-named-that-city’s-official-song) “I Left My Heart In San Francisco.” Not a song, though, not a performance, but an invitation to take a trip. (“If you wanna go, clap your hands, clap your hands now, clap!” We did.) Chanting the intro (Bennett never thwumped a crowd the way this guy did), and then rocketing into an improvised delivery of the (same old, but not really) lyrics, and we were there (that may have been what yanked us off our collective ass). Yeah, fine group-let’s hear’em s’more.

Then 1 split for dinner, despite Hampton Grease Band, who were, I understand, extreeeeeemely greezy, thwacking the skulls of the straight voyeurs with “Gimme an E G G S: EGGS!” (Whaduzitmean, whaduzitwmean?? Suck you ), and putting the Mobe leaflets distributed on the fringe of the park (dig?) to fine functional use the airplanes still filling the air long after I returned just in time to hear the Allman Brothers launch their own airplane.

Which circled for about forty-five minutes before coming down for a landing, hearing occasional reports from the control tower about topographical conditions (“First there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is”), and cooking up a fine in-flight meal of intricate interplay, lead bass-rhythm organ, spiced occasionally with individual riffs. Hard number to top, but the rest of the set demonstrated what has been known and said well: the Allmans lay down fine, solid, gimmick-free sounds that do indeed work on you, if not as evocatively as Lee Moses (or the Hampton Grease Band), certainly as thoroughly Before Mother Earth the day’s last rap for funds (how to solve the dilemma: either admission charges or sugar daddies. The festival itself an attempt at synthesis: $1 donation, but when I dropped my buck into the box the attendant responded with “Far out,” like maybe not too many dollars were dropping the final balance sheet on the festival will be most instructive, and, I fear, sad) and a check to make sure most of us had got off (on?). ‘Feared we had.

Then an improvised Mother Earth, short I understand, some personnel with Boz Scaggs added. Interesting-combination, creating a multi- focus group like Crosby et. al. or Blind Faith. Scaggs, and Toad Andrews traded off the lead, and the group changed coloration accordingly. As it also did, understandably, when Tracy Nelson, sang, the sound pouring from her mouth caked with clay, and oozing the richness of a stout young taproot. They were about the transcendence of atomized clouds, the building of power that occasionally thundered over us Saturday in sheets of undifferentiated energy. And when it all came down to borrow from the group’s title song), it was about the basics of life: love, sound health (“I Don’t Need No Doctor”), and making do.

The festival ended Saturday night at 10; permit ran out. But suppose it had not. Then why end at all?

(Concluding park-generated fantasy: how to make revolution. Suppose, I dreamed, enough groups got together to maintain continuous music beyond the saturation point. Two, three, four solid days. So that people could leave satiated, not fearing that they would miss anything/too tired to care. But leaving with the desire to keep it going, for what is more worthwhile, fulfilling, rewarding fuck it, FUN, than a festival? Not, of course, simply for the music, but for the communal consciousness: the shared joint, the freely given and received) food, the common caring for each other. And so people leave just to re- turn, but with sustenance for the festival. Bring back food, or dope, or bread for the generator. Take a job for two days, rap (automatically, unconsciously) on the job about the festival, come back, bringing three new freaks from work. Extrapolate extend the vision, so that ever more complex tasks are perceived and done to keep it going. So that the tribal existence is carried beyond the festival site; all life is viewed through the lens of the festival; all tasks are performed in order to get back to the festival, bringing something with you: food for ten folks, dope for 20, $40 for the electricity. Then it gets too big, so groups break off, start a new tribal campground, and it builds and grows organically, as revolution must in a country which is controlled in no one place, simplistic “Marxist” analysis to the contrary not withstanding. Until the old folks disappear bemusedly, and nobody wants to be PresidentGovernorSenator- MayorPig, and the whole world is a rock festival.

But.)

The permit did expire.

-Greg Gregory

Sunday

SUNDAY: after almost two entire days of a fucked up sound system, Sunday’s concert was a pleasure to listen to. The crowd, although sparse early in the day grew to several thousand by nightfall, and still exhibited its beautiful spirit of sharing, with much free grass and fruit circulating.

The old “star” system prevailed, and the local groups played during the afternoon. First to play was Radar, who sounded good for two reasons: one, the sound system was functioning properly, and two (more important), their material was enjoyable. After two days of almost all blues, good old rock and roll was a welcome relief. And they played it well, seeming to enjoy it as much as the crowd did. Only fault of this popular local group was a drum solo which seemed to be added on as an after-thought, especially because no other members of the group did soloes.

Following Radar came an unimpressive, but nice jam session, with the lead guitarist of The Second Coming, the bassist and drummer of the Allman Brothers, and organist and harmonica player of Mother Earth.

Next, the incredible Hampton Grease Band. Saturday they had destroyed the audience with their playing, and Sunday was no different. Playing a great version of “Wolverton Mountain” among their numbers, they again finished up only to have the audience bring them back for an encore with chants of “More, More!” After a set by an unknown Black group, came The Sweet Younguns. Unfortunately this group has been hung up playing too many high school and college dances, with the resulting Top 40 commercial sound demanded by these events. But Sunday night they proved that they have great potential, and given the proper environment to explore this potential, they could become a really first-class group. Their excellent singing and playing are already quite evident. Also they possessed some of the finest equipment seen and heard during the festival, and they used it effectively.

Lee Moses returned to play again, after a really exciting performance Saturday. Their fine blues playing was one of the most popular acts of the weekend, and included an incredible version of “Love Is Blue” as well as “Hey, Joe” and some other more traditional blues numbers in the style of B. B. King. Real blues, and really singing the blues as well! And a real mind-blower for a finish a young boy about 10 or so came out on stage to play drums on Moses’ last number, and quite well, too!

Finally nighttime, but sadly no light show. Especially sad because Friday night’s show was the Electric Collage at their best. But the Allman Brothers made up for it. Little more can be said about them, other than the fact that only The Grateful Dead in Piedmont Park have generated the same energy that was created Sunday night. The whole experience was highlighted by a lovely girl dancing beautifully on stage.

And so ended Sunday night, but not before two couples were married on stage by a minister of the Universal Life Church, as a finishing touch to the Piedmont Park Music Festival.

-Charlie Cushing

By Bill Mankin

[Originally written for ClassicRockPage.com]

Early June 1970, Byron, Georgia: The advance team / construction crew arrives. Our mission: build a rock festival. This would be my fifth, and last, rock festival experience during those heady three years between 1968 and 1970 when the rock revolution burst out of indoor arenas into the grass and open air. Oddly enough, even at the time it felt like the end of an era. But as I drove down to Byron that first day it felt like the beginning of “Bill’s Excellent Adventure.”

Byron would also be my second rock festival as an actual employee, in both cases working for the team of seven promoters who had produced the first Atlanta International Pop Festival one year earlier. I could barely stand the wait for this one.

Memories from the previous summer’s Atlanta festival were already giving me great expectations: backstage chat with Janis Joplin; on-stage arms-length vantage point for Led Zeppelin’s set; a quiet hotel-room discussion with Jim Morrison and one of the festival’s promoters in an unsuccessful attempt to convince Morrison to bring the Doors to the festival; … and MUSIC! God, the music!

For me, the music was the point. In 1969 I had worked before the festival distributing posters and other promotional materials, but had declined to work during the festival so I could concentrate my full attention on enjoying the music. By 1970 I was evidently ready for a deeper commitment. So I signed up for the construction crew and in early June moved to a rag-tag campsite next to the Middle Georgia Raceway and the soybean field that would soon welcome the musical masses.

My tent-mate was a guy named Sandy, actually “Psychedelic Sandy” in his college radio DJ persona. The tunes he had spun on the radio a couple of years earlier had really expanded my musical mind. But in reality he didn’t look at all psychedelic, nor for that matter like a construction hand ready for a month of heavy sweat and poor pay. But there he was, like me, trying to get as close as possible to the high energy, counter-cultural tidal wave of live rock’n’roll.

Our campsite was initially inhabited by about thirty similarly inclined long-haired aficionados from throughout the Southeast, mostly males. The women that came with them ran the campsite and cooked three great meals a day for the crew (what can I say, this was 1970). The facilities were rustic but the camaraderie – and our mission – more than made up for it. When necessary we could even be pretty inventive, such as with our daily showers.

The Middle Georgia Raceway, a small oval blacktop track, had an appropriately-sized fire truck – a pickup truck with a square metal tank in the back holding 300-400 gallons of water in a pressurized tank. Every day one of our crew would go fill up the tank and drive the truck back to the campsite. Everyone, men and women, would strip; we’d all get sprayed down; we’d soap up and scrub ourselves; then we’d get blasted with spray again – en masse. It was great fun. It was also interesting that the local sheriff would sometimes manage to time his daily rounds so that he could drive out from town and through the campsite just about shower time. I guess he decided not to arrest anyone for public nudity so that he could come back again another day. [By opening day of the festival the guy had become a pretty good sport – he even proudly displayed a smiling pig face someone had drawn for him on his squad car door.]

Our primary job was to build an eight-foot tall plywood fence around the entire, soybean-covered festival seating area. This was a big job – about 24-acres worth. And after a couple of weeks it got old. Once I was asked to collect wild blackberries for the morning pancakes… much better than building the damn fence. It was a welcome relief to join the crew working to build the spotlight towers or the stage, just to get a break. The spotlight towers were really something to see – soaring triangular platforms built high up between three huge tree trunks sunk into the ground, like telephone poles but much bigger, each painted a single color – red, white or blue. Erecting the scaffolding to build the platforms was tricky, and required both caution and stamina. Although the sunsets from the top were a sight to behold, after a day of it I was ready to go back to fence-building; it was much safer.

During the construction phase some of the area newspapers gave the festival a media buildup. I managed to get my photo into two articles. My favorite was the Atlanta Journal-Constitution article (6/28/70) headlined: “Hippies Working? And They Don’t Bite!” The article went on to list some of the scheduled musical acts, describing Jimi Hendrix as someone who “makes funny noises with an over-amplified guitar.” You get the idea. The reporter obviously didn’t.

Did I mention how HOT it was? I would awake in my tent every morning… sweating. One day during the festival I felt so desperate when I woke up that I grabbed someone’s ice-filled cooler and dumped the whole thing over my head – a truly unforgettable rush! Needless to say, the heat made the porta-potties a real challenge; every conceivable alternative went through your mind as you approached the door – and every time the door opened you’d suddenly think of more.

Several things made this festival feel very different from others I had attended. It had been almost a year since the unexpectedly large crowd at Woodstock had forced its promoters to declare it a “free festival.” We all wondered how big our own crowd would be and whether fences and tickets would mean anything in Byron. Soon enough, as opening day approached and the crowd swelled, we heard the cries of “Music should be free for the people!” Then, even before the gates opened, all our hard work erecting plywood was for naught and the fences fell. Oh well.

The main thing, however, that made Byron different was Altamont. Combined with our feelings of expectation and excitement about the music ahead, Altamont gave Byron an added, subtle, edge of dread. Only six months earlier in Altamont, California, an audience member had been murdered in plain sight of a rock festival stage by members of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle club. The aftermath produced a dark cloud that spread all the way to Byron, Georgia. Although it was nearly invisible in the middle-Georgia sun, we felt it was there anyway, hiding and waiting. We just didn’t know if it would appear or not. The best we could do was try to ignore it. Sometimes that was hard to do.

About a week before the festival opened someone had found a girl in the woods across the main highway whose face had been beaten so badly it no longer looked human. One of our crew had brought her into our campsite where she was hidden as she recovered. The word was that she had tried to leave a biker club and was met with a violent ‘NO’. As opening day approached we began to see more and more bikers riding around the festival grounds, some armed. Once as I was leaving the back-stage security gate to head for my tent I passed a biker with a pistol on his belt. He was sitting on his bike, gunning the engine, acting as though he was going to be admitted through the gate without a backstage pass. He was. Fortunately, once the masses of music lovers arrived, the good vibes vastly outnumbered the bad.

By opening day I had maneuvered myself from fence-builder to stage-hand. It was exactly where I wanted to be – as close to the music as possible. Unfortunately it was about the worst place to be from a musical standpoint – the sound was really bad. It was virtually impossible to hear the vocals above the bass & guitar amps and drums. But it was still hard to complain – the excitement level was intense! There’s no good way to describe what it’s like to stand next to a high-decibel rock band at full tilt with a several-hundred-thousand-strong mass of humanity spread out in front of you, swaying to the beat and cheering at every crescendo. I guess I can always listen to records at home, I told myself. This is something else!

On a couple of occasions I also managed to step up to the microphone between performances to deliver some of the obligatory public service announcements all rock festivals were known for. You know: “Don’t take the purple acid, people!”; “Hey, if you lost a kid named Sally, you can pick her up at…”; that sort of stuff. Actually, I have no memories of what I said; I can only hope I was at least coherent.

Stage crew duties were hard work but fairly routine, that is until about the middle of the second day when the plywood surface of the stage had begun to suffer from the repeated rolling of heavy, wheeled music gear. It had developed some wrinkles and ripples, which then made some spots unstable. One night, during Mountain’s performance, I ended up having to baby-sit their seven-foot-tall, double-stacked wall of Marshall amplifiers, which were rocking ominously with massive lead guitarist Leslie West’s every move. If that wasn’t enough, I soon sensed something behind me and turned to find another wall – of bikers, all without stage passes but standing very resolutely, arms folded. I did my best to do my job and avoid being crushed by either wall. By the way, Mountain was great! And loud!

When I wasn’t on stage I was usually too tired to do much of anything else. One day I was so hot and tired I crawled under the stage to try to sleep in the shade, with blaring, bouncing rock bands just ten feet over my head.

For me the most memorable performance I witnessed was Hendrix, who took the stage late on July 4. Although it was not actually my work shift during his set (and thus I was technically not supposed to be on stage), I was determined to get as close as I could. So I crept into the shadows about twenty feet from Hendrix’s microphone and tried to stay out of the spotlight pools. My reward was something I will never forget. Again, although the sound was not the best, the sights were: midnight, Jimi’s otherworldly performance, a light-show on a raised rear-stage projection screen, fireworks, even someone’s lear-jet screaming in a low pass overhead. It was more than sufficient to mesmerize and hypnotize, which is apparently what happened to at least one observer – Biff Rose. On the opposite side of the stage from me, quirky songwriter/singer Rose was sitting like a stone(d) statue, face staring wide-eyed heavenward, mouth wide open… for what seemed like a very long time indeed. I can relate, Biff!

As seemed typical with every festival I ever attended, the last act would take the stage long after the published schedule had originally indicated. In Byron it was sunrise by the time Richie Havens walked on stage, pulled up his wooden stool and sang for us. I was dead tired and had crawled up to a scaffold platform at the side of the stage, where I looked down on Richie. What was left of the audience were mostly sprawled on the ground, asleep or otherwise immobile. I loved Havens and had seen him many times. His was a true festival persona, and his music was a perfect and welcome accompaniment to such events. As I recall, he opened his set with “Here Comes the Sun.” What else? By the time he finished his performance, the whole audience was on its feet swaying and singing along. So was I. The Woodstock generation was alive and well and would survive to live another day, smiling all the way. I took Richie’s stool home with me that day. I still have it.

Then it was over. Nothing left but the remnants. As I stumbled down to the stage I noticed a familiar face in the audience, like a needle in a haystack – a friend from college. He was just as surprised to see me as I was to see him, and our faces both burst into double-wide smiles. We would have a lot to talk about next semester, when I would also become stage manager for the University of Miami’s rock concert series. But that’s another tale.

The remnants of rock festivals always intrigued me, and as tired as I was that final morning I made a special point to wander through the field in front of the stage staring at the trash and trinkets left in the wake of the musical mayhem. I was not searching for treasures, just staring at whatever was there, like an absent-minded archeologist, not really expecting to find anything worthwhile, but still interested enough to make the effort. Now that I reflect on it, I think I was probably trying to hold onto the crowd, the energy, the music for just a bit longer… to keep it from ending, to hold onto the remnants long enough to re-build the magic. I’m sure that’s why, as I drove with a friend back to college after Christmas break at the end of the year, we stopped by the Byron festival site early one morning to pay our respects. The spotlight towers were still standing, so we climbed up. It was sunrise again and everything still seemed possible. If we tilted our heads just right we could almost hear the music.

Fortunately, Byron was not a second Altamont. It was the Second Atlanta International Pop Festival. I’m still sorry there wasn’t a third.

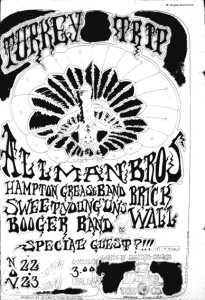

The Turkey Trip was to be at the Duke Tire warehouse at 11th and Peachtree right on the Strip. As often happened, the night before the event the place was hurriedly condemned by the city. The concert was moved to the Georgian Terrace and the price was raised. Many were upset, but the music was fabulous. The Allman Brothers had just released their album and were in high form. The Hampton Grease Band was wonderfully greased. Special guests were Knowbody Else.

The Turkey Trip was to be at the Duke Tire warehouse at 11th and Peachtree right on the Strip. As often happened, the night before the event the place was hurriedly condemned by the city. The concert was moved to the Georgian Terrace and the price was raised. Many were upset, but the music was fabulous. The Allman Brothers had just released their album and were in high form. The Hampton Grease Band was wonderfully greased. Special guests were Knowbody Else.

Their lead singer kept his head down and long locks hanging as he hid beside the drummer. But his growl was like an old bluesman.

Soon after they changed their name to Black Oak Arkansas and the singer emerged with bleached hair, buff naked chest and buckskin pants to prowl the stage as Jim Dandy Mangrum.

The success of this location led to the opening of The Electric Ballroom here.

Jim Stewart’s first entry into the Rock Music arena was his engineering/production work on the psychedelic band known as The Knowbody Else. A lucky break came when Phillip Rauls was promoting their STAX record and contacted by the management team of Iron Butterfly inquiring about an opening act for their forthcoming show coming in Memphis. As it turned-out, The Knowbody Else opened the Iron Butterfly’s show and created such a splash with the audience that Iron Butterfy’s band members became impressed and offered the local band a permanent position opening for their U.S. tour. The Knowbody Else then changed their name to Black Oak Arkansas and signed a long term contract with Atlantic Records.

My wife and I were there. I have more memories than I could think about typing. I started at the Catacombs, lived at Middle Earth and vaguely remember a head shop on W P’tree at 14th…I think. That would have been ’66 or ’67. It seems like the strip started when Atlantis Rising got established…the place to be. I lived all around the park. By ’68 I was living at “The River House” up on the ‘Hooche. Brought Renée, my wife, up from FL in June of ’69. We were married 07/07/69 at the “Free Concert” in the park after the 1st Atl POP. I got popped in early ’70, which removed me from the scene, but didn’t kill the memories. Sadly, only 2 pictures have lasted as long as my marriage. Bob Oldsroyd, red headed Bob, was always taking pictures. Has he turned up?

Schroeder & Renée

[When Schroder was arrested the headlines named him ‘Acid King of the SouthEast’. We were lucky enough to get an interview with Schroder. Due to double jeopardy, he was able to talk openly. He and Renee had a great hippie love story. Married before the Grateful Dead played Piedmont Park, they remained in love until his death in 2011. Listen to his interview.]