The Great Speckled Bird Vol 3 # 5 Feb 2, 1970 pg. 2

McGrease

The rock concert at the Sports Arena Sunday was a good thing both in itself and, hopefully, as a sign of things to come. Must have been 4,000 people turned out to pay $3 or a little better to listen to the River People, Radar, the Hampton Grease Band, and Fleetwood Mac.

The Arena is a ramshackle building long used for local wrestling, boxing, country music, and square dances. Inside, the atmosphere is one of wood and honest corruption, not steel, concrete, and hydraulic hype. Outside, the feeling is, well, like the industrial part of town, you know, warehouses, steel mesh fences, truck loading docks, cotton mill buildings, and even some plain red dirt road dear to the heart of a country boy. A good place for a Saturday night dance. Altogether the scene recalls the good old rock n’ roll shows of the ’50s more than the superstars, Fillmore’s, and festivals of the ’60s.

So there are the River People leading off the show, officially together only a couple of weeks, performing a mixed bag of music, some countrified, some bluesy, relaxed and competent behind good “lead” bass guitar work by John Ivey and vocals by Wayne Logiudice. Some more time in the woodshed and they will have a mellow together sound which will make a very pleasing addition to the music scene here.

Radar followed, laying down some interesting riffs as always, outstanding among them being “Crab Nebulae” and the old warhorse “Godzilla.” I am not a great fan of these science fiction-inspired epics, especially the second or third time around (too much literature and not enough sound), but at least in this case the holes were filled in by good keyboard work and an exceptionally fine drum solo. Radar is at present a lightweight group but may get it on yet, should they ever decide to strike out for the edge.

The light-fingered Grease grope, however, is another order of magnitude—or something. The immortal Hampton, leader of the grope, materialized in the limelight to lead off the set and performed the ultimate putdown of any and all guitar solos that ever were or will be, including Hendrix, Page and Townsend! And it totally confused whatever musical expectations the audience might have had. Captain ornu Greaseheart then “took a saxophone and the band into an egg-sucking number which betrayed influences of Coltrane, Zappa, Pharoah Sanders, and AM radio feedback. Grunts, yelp, words, harmonies, discords, rhythms and counterpoints welded the audience together in a miasma of jelly. Glen Phillips and Harold Kelling, amply supported by the wild drumming of Jerry Field and the elaborate bass figures of Mike Holbrook, stretched out into an amazing play of lyrical guitar lines that seemed to have no horizon.

“They play music that sounds like music feels (!),” said the beautiful blonde, stoned. Well, it got me off said the beautiful blonde, stoned. Well, it got me off, too. Great to hear how much tighter they have got since last hearing them, some months ago. Apparently the set was cut short because of time hassles, but Hampton close closed with a “Rock Around the Clock” that brought the audience to its feet-some of them even getting religion, or so it looked-and the farthest out band around these parts left the stage.

It was a tough act to follow, and I expected Fleetwood Mac to be something of a downer, but mercifully was wrong. The Mac, having been through the school of John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, came on slow, playing standard “British blues,” almost funky and almost real, after a couple of numbers, which revealed a strong drummer and some nice slide guitar, they warmed up a bit, got into a good cook with “Oh, Well” (one of the fives of PLO) and proceeded to get it on, lining out rhythms Grateful Dead-style and turning up the amps and the energy and the crowd to a fantastic level. Running at times from two to four guitars and packing almost as many amps as Johnny Winter/they were not short of volume. Furthermore, when they finished working their piece through its guitar changes, they stopped and began again with percussion instruments. While perhaps not as flexible as the Watts 103rd St. Rhythm Band or your black neighborhood kid garbage can ensemble, they made folks feel good, and received a standing ovation.

The Sports Arena could well be the focus of a good music scene in Atlanta if people will only stop fucking us over. The vibes in the place were fantastic and acoustics are not all that bad. The promoter of the concert has a jive rap (“Give me the signal!” he shouted, held up a V-sign, only to be faced with an array of upraised fists) but apparently not a bad heart, for the absence of hordes of helmeted pigs was certainly commendable.

One suggestion—room for people to dance—say the rear of the main floor area-when the spirit moves them. Give the people room to move! Yes! Room! To move! Peace Brethren.

—cliff enders, -with a little help from some friends

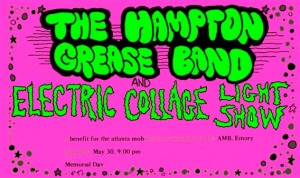

The Hampton Grease Band were a main stay of the community and seemed always ready to play for a good cause. This show was memorable because I was at Emory and knew the Young Republicans who supported Nixon and his Vietnam policy. They stopped just short of being pro-war activists.

The Hampton Grease Band were a main stay of the community and seemed always ready to play for a good cause. This show was memorable because I was at Emory and knew the Young Republicans who supported Nixon and his Vietnam policy. They stopped just short of being pro-war activists.