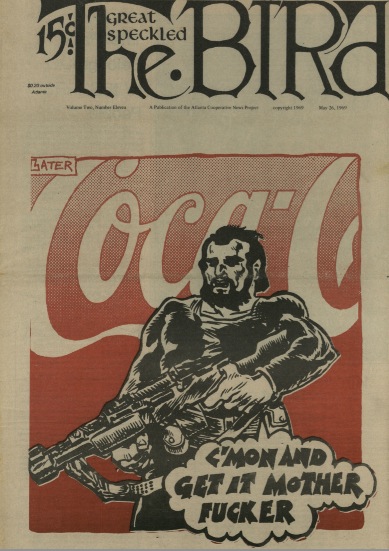

The Great Speckled Bird 5/12/69 vol 2 #9 p11

[The layout of the following article and lyrics was nonlinear, with sections and paragraphs arranged around photos and other graphics.]

“I will secretly accept you,

And together we’ll fly South.”

“Leave your stepping stones behind

There’s something that calls for you.

Forget the dead you left, they will not follow you.

The vagabond who’s rapping at your door

Is standing in the clothes that you once wore.

Strike another match–go start anew,

And it’s all over now, Baby Blue.”

“And I’ll tell it and speak it and think it and breathe it

And reflect from the mountain so all souls can see it.

And I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

And I’ll know my song well before I start singin’.”

“In a soldier’s stance I aimed my hand

At the mongrel dogs who teach.

Fearing not I’d become my enemy

At the instant that I preached.

My existence led by confusion boats

Mutinied from stern to bow–

Ah, but I was so much older then,

I’m younger than that now.”

Bob Dylan chronicles a newborn musical soul in fetters: hillbilly theatrics and black-face minstrelsy stifle its expression and obscure its real identity. The guitar is raucous and untutored, its forms a parody of the strengths of black bluesmen and white troubadours who sang of hard times. Only the harmonica sings. A rough, fresh humor explodes through all the tradition and the intense preoccupation with death. The sound is uptight, confined. Woody Guthrie is mentor.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan begins the pendulum swing away from the experience of the black man. Traditional white folk and “topical” forms are explored and expanded in a relaxation of the musical tensions of the first album. Interaction between voice and guitar is the keystone–both rough, both searching for a style and a form, but this time creating music in the process. Superlative harmonica offerings continue to hold the straining parts together. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” presages the sounds to come: a perfect musical and lyrical creation with guitar, vocal and harmonic textures intermeshed in an autonomous unit. The humor is still present, tempered by a growing bitterness.

The Times They Are A-Changin’ continues the reformulation of the topical “protest” song, but this time the humor is absent. The singer becomes a preacher. The harmonica is distilled sadness and anger and fear while the guitar learns discipline.

Another Side of Bob Dylan is the nadir of instrumental and vocal performance. Previous song forms are now totally inadequate: the new wine is bursting the old skins. The voice is increasingly strained and laden with self-pity, the instrumental accompaniment demoralized.

The next album is Bringin’ It All Back Home, but the trip is not into the past, but forward into the present. The sound turns on. Electric instruments are added. The total music is more alive than ever before. The term “folk music” is reinterpreted: the sounds which once came from the broadside now emanate from the jukebox. Teenagers all over the world have the subterranean homesick blues. There is a force, a fire long absent or suppressed. The harmonica soars, the electricity flows freely through the new expanded instrumentation, and the voice begins to work within the path created for it by the music: Guthrie has become the tambourine man.

Highway 61 Revisited lets it all hang out. The musical psyche of youth weeps, laughs and lashes out violently at the absurdity of the old forms it has inherited. Freedom is not a goal to be won; freedom lies in the struggle against these old forms. It is a personal as well as a collective thing.

Blonde on Blonde expands the electric sounds further and mellows them. Musical subtleties abound. Everything bristles, everything sings; the song, the singer, and the sound find a new realm of wholeness where they can move together. The turn-on has proved permanent and produces a vibrant palette of tone colors.

John Wesley Harding is a distillation of all that has gone before. Instrumentation is simpler, more pungent, the song forms less complex and more elliptical. The sound plunges deep into the roots of white country music, and the voice handles its new eminence with grace. The forms are more regional, yet, mystical, more traditional, yet freer, pop but earthy. The voice evokes, it does not preach.

Nashville Skyline is the birth of a new voice: Dylan sings! Both the harmonious and discordant elements latent in the first album are now fused and reintegrated into a new sound. Johnny Cash joins Woody Guthrie. Humor returns not as an imp but as a lover. The old has produced the new. Dylan is now the country cosmopolite. Another struggle, another cycle begins.

The young Bob Dylan is full of words, but they are not his, nor are the forms in which they are expressed: the song is either “to Woody”—

“Here’s to Cisco and Sonny and Leadbelly, too

And to all the good people that traveled with you;

Here’s to the hearts and the hands of men

That ‘come with dust and are gone with the wind”,

–or the experience it speaks of belongs to the black man.

“I’m walkin’ kinda funny, Lord,

I believe I’m fixin’ t’ die.

Oh well, I’m walkin’ kinda funny, Lord,

I believe I’m fixin’ t’ die.

Well I don’t mind dyin’ but I hate t’leave my children cryin’.”

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan begins to make his own personal statement, but the old forms continue to dominate. Enter the “message”. Even here “issues” become a cul-de-sac, and moralism gives way to a desire for change itself. Former issues of Right vs. Wrong are compressed into one comprehensive issue–new vs. old: “Get out of the new road if you can’t lend your hand/ For the time’s they are a-changin’.”

This new emphasis upon a radically altering universe of values opens a door to a whole new experience. A verbal manifesto is required as a ticket to ride.

“Good and bad I defined these terms

So clear, no doubt somehow:

Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now.”

Love is impossible. “Go away from my window.”

Bringin’ It All Back Home: Rock and Roll brings it all back home to the 20th century. Folk means pop, and the lyrics become looser with greater room for complexities and shifting priorities of meanings. The new freedom allows a place for love minus zero, no limit.

Highway 61 Revisited submerges the Word, now harsh and biting into an orgy of imagery and electric sound: “the songs on this record are not so much songs but rather exercises in tonal breath control (B.D.) “‘Message Man” is now the villain of villains:

“You’ve been with the professors

And they’ve all liked your looks.

With great lawyers you’ve discussed lepers and crooks.

You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books,

You’re very well read, it’s well known–

But something is happening here, and you don’t know what it is,

Do you, Mr. Jones?”

The word clusters are now too dense and evocative for any “message” Mr. Jones the Print Man might be able to seek–“There oughta be a law against you comin’ round/ You should be made to wear earphones!”

Blonde on Blonde accepts the new complexity as basic. The savage humor is mellowed and the love strain is amplified. The sprawling, inward turning images can construct a hymn to a “sad-eyed lady of the lowlands” or say simply, “I want you”.

John Wesley Harding compresses the lines into stark, enigmatic song forms in which “Nothing”–and everything–is revealed”. The simple eloquence of country music lyrics is inspiration. Song and setting are one and the same. Words are a means of expression for the voice, now used as an instrument within a total sound.

Folk, pop, country, rock – Nashville Skyline reformulates all the lyrical ingredients of all the previous verbal concoctions into a new, whole in which the voice supersedes the song–“love that country pie”.

Bob Dylan is schizoid, an explosive energy source of youth in a new age struggling to express itself in old forms. Black experience is exploited ruthlessly and wars with the spirit of the dust bowl. A young soul is stretched taut between competing masques. Intuition and fear of death is accurate, but it will be a psychic death, a destruction of the ego. Precariously balanced equilibrium.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan has some room to walk around. The mannerisms and affectations of false experience are channeled into more accommodating vessels. Preoccupation with death becomes horror at the condition of man in the 20th Century, and fear of The Bomb. White folk forms are infused with humor and the balance is maintained.

The Times They Are A-Changin’ tips the scales to the dark side. Humor is gone. Despair, outrage, protest, even vengeance come to the fore. Change is seen as an end in itself.

The split occurs in Another Side of Bob Dylan. Uncertainty rules. The old answers become questions. Withdrawal, beginning of psychosis. Turning inward. There is only one issue now: being “hung up.”

Bringin’ It All Back Home discovers a new source of strength with which to face the trial ahead: electric rock, a new folk music for a new age. The door to the unconscious is opened, the past is irrevocably past.

Highway 61 Revisited gets down in it. All travel is within the psyche. The outside world is a manifestation of the horrors within. Chaos reigns, humor is savage. New forms, new shapes, all is accepted.

Blonde on Blonde reveals a psychic implosion. Dylan gracefully rides the crest of his own mind wave. He has found his own frequency, and the love and humor can again have free play. The conscious and the unconscious are opposite sides of the same experience.

John Wesley Harding forms a synthesis. The wounds begin to heal, and a new vision appears. Rage and humor mellow into wisdom. White soul roots are deeper, flight is unrestrained. Passage from within to without is smooth and free. The Self.

Nashville Skyline is the birth of a new voice. All elements are balanced. Free-flowing sound. Wounds have become strengths. All blends into the love strain. Integration of the individual into the world. A new cycle begins.

“Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re tryin’ to be so quiet

We’ll sit here stranded, though we’re all doing our best to deny it

And Louise holds a handful of rain tempting you to defy it

Lights flicker in the opposite loft

In this room the heat pipes just cough

The country music station plays soft,

But there’s nothing, really nothing to turn off

Just Louise and her lover so entwined

And these visions of Johanna that conquer my mind.”

“Now the moon is almost hidden

The stars are beginning to hide

The fortune telling lady

Has even taken all her things inside

All except for Cain and Abel

And the hunchback of Notre Dame

Everybody is making love

Or else expecting rain

And the good Samaritan he’s dressing

He’s getting ready for the show

He’s going to the carnival

Tonight on Desolation Row.”

–miller francis, jr.