Reprinted from The Great Speckled Bird, vol. 3 #27 July 10, 1970

Reprinted from The Great Speckled Bird, vol. 3 #27 July 10, 1970

Community

It has been said that you have to understand the past to know the future. Freaks don’t necessarily believe that. We’ve seen how our parents have used the past as an excuse for standing still. In our lifestyle we are attempting an affirmation, not of the past, nor the present, but the future.

Now though, after several years of growth, the hip community in Atlanta does have a past. There have been important struggles in Atlanta-struggles for the street, for the park, for store-fronts, for our own institutions, for unity against straight Atlanta’s rulers. This is our history and we can learn from it.

For years, the Midtown area of Atlanta has been the center of a small bohemian colony. It grew around the Atlanta Art School, located on Peachtree near 15th. In those days (late fifties) before the corporations decided that art was a necessary part of good business, the Art School was a pretty open, groovy place. One of the first coffeehouses, The Golden Horn, opened near the Art School during the folk music craze begun by the Kingston trio. At the time the only place you could see quality foreign films was at the Peachtree Art Theater, and near it were two of the best record shops in town. Grass was plentiful and if the cops busted a party for too much noise or something they didn’t know to look for it or know to recognize the wonderful sweet aroma.

Not all was peaches and cream, though. Before the Golden Horn, a coffeehouse had been opened on West Peachtree and busted on opening night. The owners were busted for operating a dive and for obscenity from Playboy pinups upstairs in a bedroom.

The economics of the neighborhood supported the colony. With the flight to the suburbs in the mid-fifties, the neighborhood had been surrendered to working class whites and rents were pretty cheap. Rentals of storefronts were relatively cheap since many merchants in the area moved to Ansley Mall when it opened about 1965.

In 1966 a student at the Art School, David Braden, opened an Art Gallery on the north side of l4th. That was Mandorla No. 1 and when he moved it to the corner of Peachtree and 14th it became Mandorla No. 2. In the basement Braden opened a coffeehouse-The Catacombs.

Braden was gay and was out front about it. People respected him for that and for the openness of his gallery to new art. In the summer of 1967 when kids, mostly from metro Atlanta, began to come into the area, Mandorla was the natural place to go. A few hip people began to sit on the porch or on the wall across the street.

Summer of 1967 was the Haight-Ashbury summer, and news media across the country began looking around their towns for hippies. Atlanta was no exception; They found Braden and made him into the “leader of the hippie colony.” The cops got uptight, and Braden was busted for possession in November 1967. He got a year’s suspended sentence for that but in March 1968 he was busted for selling to a minors- a police frame-up. Braden had attempted suicide and when his lawyer pleaded him guilty, his charge was reduced to simple possession. He’s still in jail, one of many taking the rap for the rest of us.

Six hours after Braden’s second arrest, the vice squad raided the Morning Glory Seed, Atlanta’s first headshop, located on West Peachtree near North Avenue. The owner was a friend of Braden’s who had helped him with the defense in his bust. Two employees were busted and a warrant was issued for the owner. The Morning Glory Seed was closed.

But the police weren’t able to close the Middle Earth head shop on Eighth Street near Peachtree. They did try, though. The Middle Earth was opened in November 1967 by Bo and Linda Lozoff. They opened with a poetry reading by an Emory professor. The cops came that night and practically every night after that, hassling customers, hassling Bo about his cycle, threatening arrests for “obscene” posters in the shop. Bo fought back and kept his shop alive.

Spring 1968 came and the warm weather brought kids back into the area. The Catacombs had been reopened as a rock club and kids gathered around the corner of Peachtree and 14th creating Atlanta’s first real street scene. Lozoff opened a branch of the Middle Earth upstairs where the gallery had been. in March 1968 the Bird began operating from a house down 14th a half block from the corner.

The city saw what was happening and sent the cops to clean it out. Kids were arrested for loitering, jaywalking, vagrancy-anything the cops could think up. Sometimes 20 or 30 were arrested at a time. Bird sellers began getting arrested for “violation of pedestrian duties.” Lozoff, who was seeing his customers arrested in his 14th Street shop, wrote in the Bird, “The Atlanta Police Department is not a corrupt arm of democracy. It is a fascist branch of an increasingly fascist society based on violence, intolerance and oppression.” He was right.

Drug busts increased with increased use of undercover narcs. Then during the summer Lozoff was forced to close his branch because the police harassment was| driving away customers. The Twelfth Gate, a Methodist Church coffeehouse on 10th Street which had earlier opened a free clinic on 15th Street, opened the 14th Gate in the space. Logoff had used. Their idea was to provide a place for kids to get in off the street, away from the cops. They had a good jukebox and inexpensive food. But the cops came in and busted kids for loitering and sleeping in a public place. Near the end of the summer the l4th Gate closed.

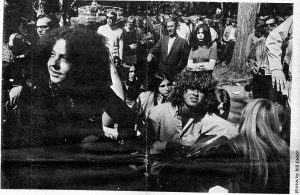

The first struggles for Piedmont Park began in July 1968.btKyn&the.spring.and summer, kids had been run out of the park by the cops. In July folks got together a Be-In. Eight hundred people showed-up. Some bands were there but the electricity was turned off. A generator was on hand but the cops stopped it. The Be-In moved to the Bird’s back yard. No real protest was made made-the community was still weak then.

The first struggles for Piedmont Park began in July 1968.btKyn&the.spring.and summer, kids had been run out of the park by the cops. In July folks got together a Be-In. Eight hundred people showed-up. Some bands were there but the electricity was turned off. A generator was on hand but the cops stopped it. The Be-In moved to the Bird’s back yard. No real protest was made made-the community was still weak then.

During the summer, at the trial of some kids who were busted at the corner of l4th and Peachtree. Municipal Court Judge Jones summed up what everyone by then knew was happening. In court he said, “I’ve never tried one of these cases before, but we’ve received complaint after complaint from business about people hanging around and taking over the area. Now these officers have their instructions, and if you’re brought into this courtroom on charges of loitering, the court is going to find you guilty.”

In fall of 68 the street scene slowed down as kids went back to school and the weather grew colder. In October a sit-in was held at the Pennant Restaurant near l4th and Peachtree after the restaurant began refusing freaks service. The Pennant returned to a policy of serving anyone.

Also in October, the Merry-Go- Round opened on what is now called the Strip. Opened by two guys who were shrewd enough to see that there was a lot of money to be made from hip culture in Atlanta, the Merry-Go-Round did well from the start. Previously the real estate interests had refused to open the strip to anything that looked hippish. Some real estate men saw that they too could make money off the hippies, and the strip was open with in most cases higher rents charged to the merchants of hip culture.

The winter of 68- 69 was pretty quiet. Drug busts continued, often concentrated in two apartment buildings on either side of the Bird office on 14th Street. In January another sit-in was held, this time at the Waffle House on Peachtree near Tenth. It too succeeded in opening the restaurant up at least for a time.

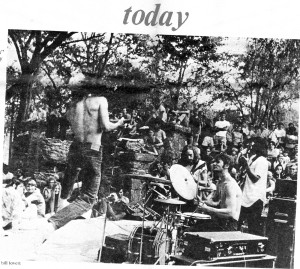

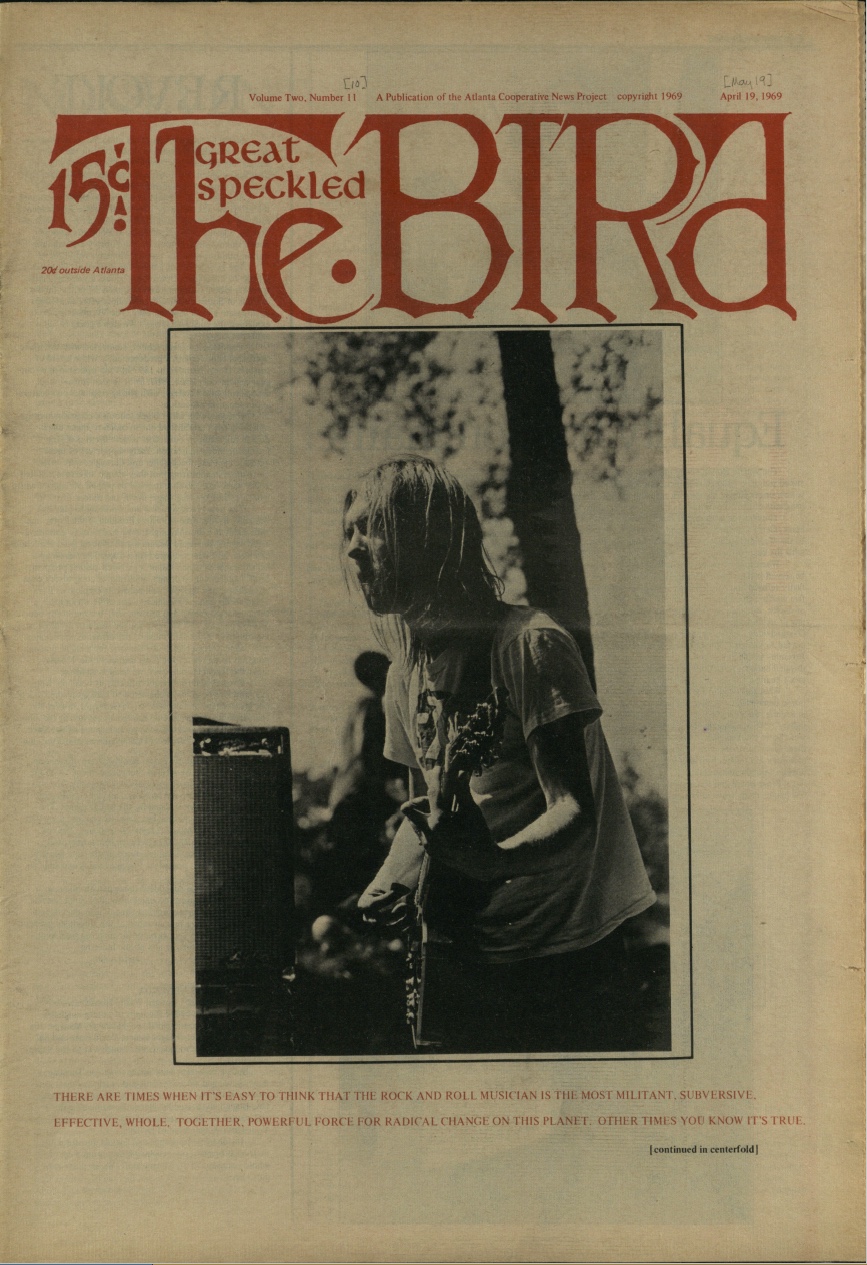

Spring 1969 opened with a Bird birthday party in the park on March 29. The Bird had discovered that there were no ordinances prohibiting the use of electric music in the park or regulating the use of the pavilion. So the celebration was held with the live, electric music of the Hampton Grease Band. The park was opened.

In April work was begun on She trade mart which was to become Atlantis Rising. The store was owned by two persons who thought of it as a cooperative in which “tradesmen” could lease space for their wares at overhead cost. For a time Atlantis became the focus for the community, with a lot of kids helping in the construction. As the street scene picked up again Atlantis became one of two places to hang around.

The other gathering place was the Middle Earth up on Eighth Street. At night kids began to gather, talk and deal on the parking lot across the street from Middle Earth. Again the city got uptight and sent the cops. Arrests on a large scale began for the same old charges jaywalking, vagrancy, etc. At times police would set up roadblocks on Eighth Street to conduct searches of cars.

On May 17 three kids were arrested at the Waffle House when they refused to leave after being refused service. Spontaneously a demonstration was held in front of the restaurant. The community was getting together. Things would be different in 1969.

Late in the winter, construction was begun on Colony Square, the office development that stands at Peachtree&14th. Older residents knew that area was slated or high-rise development but the Colony Square construction brought the news home to everybody. In the months before construction began, city housing inspectors were busy inspecting and condemning buildings to help pave the way for the developers. Housing became harder and harder for freaks to find, for their buildings were the first to be condemned.

1969 was an election year in Atlanta and the hip community soon became one of the political issues when Alderman Everett Millican, a mayoral candidate, began calling for action against the “sex deviates” and hippies in the parks and along Peachtree Street. Not to be out- hippie baited by Millican, Mayor Allen, who supported another candidate, said on June 30: “We arrest them by the hundreds for the slightest infraction of the law.” It was true: hundreds of arrests were being made on Eighth Street and throughout the community.

On July 4th, the first Atlanta Pop Festival was held near Atlanta. Afterwards more kids were on the streets. Harassment arrests continued. Bird sellers were arrested for jaywalking when they stepped off the curb.

On August 4 police conducted another large narcotics raid on 14th Street. Some of the kids were charged with occupying a dive. As the police led the kids into the paddy wagon, a crowd gathered and began chanting at the police. After ten or fifteen minutes of “Pigs Out of Our Community!” the police charged, maced, and started blasting. Three Bird staffers were charged with inciting to riot. The next week the Bird was give an eviction notice because the insurance was cancelled after someone planted Molotov cocktails in the bushes in front of several 14th Street buildings.

The community was uptight. Next week a community meeting was held behind Atlantis Rising but nothing was done. Later a community patrol was begun for a couple of weeks to try to protect freaks from police harassment.

Over the summer music had continued sporadically in the park. Late in August when tensions were highest, The Hampton Grease band gave a “Labor of Love” in the Park. It was a fine time.

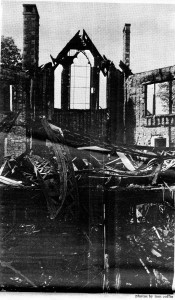

Then in September, Atlantis Rising was firebombed. Although several witnesses gave police a description of the car, no one was caught. Atlantis stayed closed over the winter.

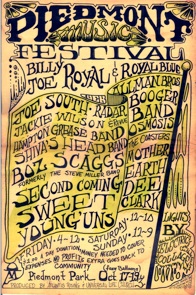

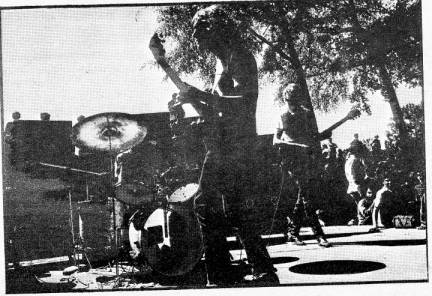

Next week the Atlanta people, with the cooperation of the community, got together a mini-Pop Festival which was to be a benefit for the rebuilding of the store. The city provided the showmobile stage and the music was held on the ball field in Piedmont Park. Several thousand people came during the weekend, but expenses were higher than contributions and nothing was raised for Atlantis.

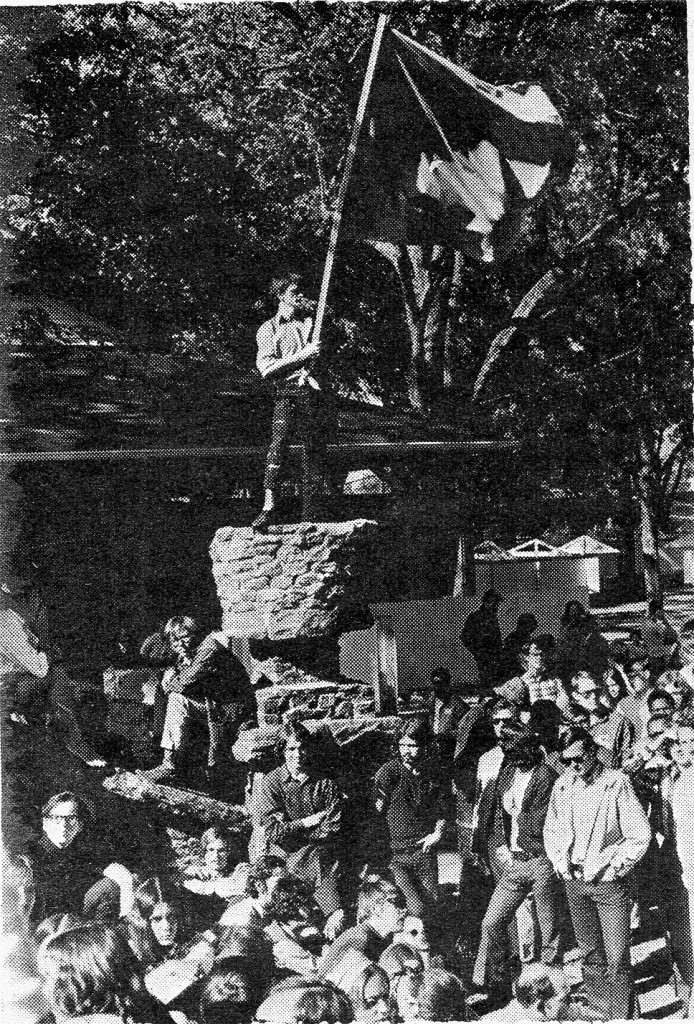

The following weekend music was held again in the park. It was on a smaller scale, with the bands back on the stone steps. A plainclothes narc was in the crowd looking for a bust. George Nikas recognized, him and started telling people. The narc tried to arrest George, A crowd gathered. George split. Cops came back and arrested Bird photographer Bill Fibben, who had been taking pictures. The crowd was angry, shouting at the cops. The cops blew their cool and started lobbing tear gas. A professor’s wife was beaten. National TV carried close-up film of a kid being beaten in the face with a billy club. The following Saturday six to eight hundred freaks marched down Peachtree Street to the police station. The community was together, and the police retreated, staying out of the community for the most part until 1970. In October a three-day festival was held in the park to claim it once again as ours.

Early in November a private social service agency, the Community Council of Atlanta, announced that it had received funds to pay the rent on a community center for six months. A community meeting was called. Kids. Bird people. Twelfth Gate folks, Harkey Kline-felter from the Street Ministry, and Universal Life Church ministers came together to form the Midtown Alliance to plan the community center. Late in December the center opened on Juniper Street providing a home for the free clinic, a place to took for crash sites, help with legal problems and jobs. For the first time lots of kids were in the community over the winter and the community center helped them stay.

In December the Laundromat opened on Peachtree near Tenth. By this time half a dozen hip stores had opened along the strip. Their merchandise was commercially manufactured, few community people worked in them, and the profits went to the owners. The Laundromat opened lo provide a non-profit outlet for community-produced goods. About twenty people opened the Laundromat as a cooperative in which all decisions would be made together. Community residents could sell their wares through the Laundromat with only a 10% charge for overhead.

Over the winter the Midtown. Alliance held weekly meetings at the 12th Gate. Other community projects developed out of the Alliance. Churches pledged money for a “Youth hostel” to provide temporary housing for freaks coming into town. The money became available in January but the churches have been unable to locate a real estate man or owner who will rent to them. A Catholic monk and a Georgia State student got together to develop a runaway program, The Bridge, to help young runaways work out some arrangements with their parents. In June they found a building but the city condemned it so they are now operating out of the community center. Hip Job Coop was opened on Tenth Street to help kids find jobs and provide an outlet for community goods. Jobs are hard to find, though. and although Hip Job has survived it hasn’t been able to get the store together enough to provide a real alternative to the straight hip merchants.

On the strip Atlantis reopened and two short order food establishments, Chili Dog Charlie’s and Tom Jones Fish&Chips, provided a focus for the street. Early in the Spring kids gathered along Peachtree to claim the street.

By the time Atlanta had elected a “liberal” mayor, Sam Massell. In February Massell had agreed to meet with the Midtown Alliance to work out ways of avoiding hassles in the coming Summer. He seemed to be committed to a different approach from the police enforcement policy of his predecessor. Bu then city employees went on strike and Massell “friend of the poor” used everything in the book to screw the strikers. A number of hip community residents participated in activities during the strike and they began to wonder what kind of liberal Massell was.

Early in the Spring things picked up on the strip. Large crowds

Gathered on Peachtree. But there were intimations of violence against freaks by outsiders. Girls being raped on side streets. The police would do nothing. The Alliance formed a community patrol to provide some protection. In late May, Chili Dog Charlie’s was bombed.

During May a young music promoter had planned a “Peace Festival” to be held the first weekend in June, was planned as a way for the community to come together to begin a summer of peace – a memorial service to those killed at Kent State, Jackson State, and Augusta. As the weekend approached the city refused to issue a permit for the park. Mayor Massell was going to make a policy statement about the “hippie problem”. Later it turned out that he feared riots from what he said he didn’t want two going on at once – one on the strip and one in the park.

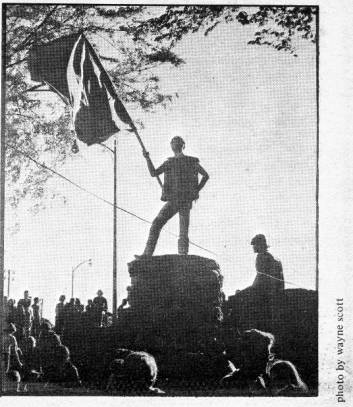

He almost did have a riot. Because of the violence on the Strip, the rapes and attacks, most people at the time did not want police protection. But Massell after a rap about protecting people’s rights, announced that he was sending in 64 cops. And that night, he did. On the Strip kids freaked out and fled to the park for a community meeting. At the meeting I expected the same old phony hassles of “peace” freak vs. “violence” freaks, but the community was together. Everyone wanted the Strip back and three to four hundred marched back to the strip to reclaim it.

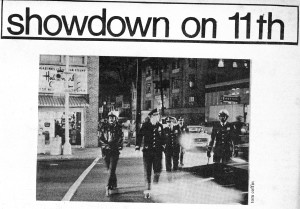

At first the cops made few arrests, but that soon changed. For the third summer in a row, kids were arrested for loitering, jaywalking, etc. Bongo was arrested taking a cop’s badge number. He was convicted by the same judge Jones who had been so candid in 1968.

Early one Sunday morning, after the Cosmic Carnival, police raided Fish&Chips and arrested 21 for loitering, including the manager and assistant manager.

This weekend a kid was sitting on the sidewalk about a foot inside the property line of the Metro skinflick. The owner, who was president of the Tenth Street Businessman’s Association, told him to move. He moved off the property line. A cop came up and said,” do you want him arrested?” The owner said yes. The kid was taken inside the theater and beaten when he protested his arrest. A crowd gathered in front of the theater. The glass on one of the doors was pushed or kicked in. The owner came outside with a pistol and shot in the direction of one group of kids.

So there it is, the same old story of harassment from the city, police. Straight businessmen. But things are changing on the strip. Every time the cops begin to bust, the odds are that the community will protest the arrest. During one bust kids were freed from the cop car. In others bottles have been thrown. The community is not going to tolerate police harassment.

Other things are changing too. The community is uptight about all the heroin on the Strip. Kids have seen how smack destroys hip communities. This week a smack dealer was physically told to stay out of the community. The Community Center is now located at 1013 Peachtree. It is working with lawyers who will represent kids in harassment arrests. The Clinic continues , helping kids with regular medical problems or kids who have bad trips or want to try to get off smack. The twelfth Gate has become more of a community institution – the one place where community bands can play and even make a little bread. The Laundromat survives, supporting around 200 community craftmakers.

Many of the community’s struggles have been successful. Community institutions have been developed. The park is ours, although we still may have to fight to continue to have music there. The street is ours too, despite the constant fight to protect it. Most importantly the community is coming together in a real way – not just during a crisis as in the past. The future will be a struggle, but if we stay together we can make it. It really is just about that simple.

-gene guerrero jr.