The Life and Death of Practically Everything except Franco’s…

The Death of the Strip by John Dennis

Huge bosoms loom from the screen. They sway a moment, then recede behind a narrow back, white bunched buttocks. Carefully entwined to hide their slumbering organs, the couple ruts mechanically. The sound track switches into fevered gasps, the same ecstasy sequence you’ve heard in the previous mating scenes. The camera moves closer; necrophilic pallor fills the battered theatre. The starers are mostly winos nursing their afternoon bottle. Fraternal, the derelicts pass their paperbags along the row for sips. Occasionally they remark on the action, comments about dominance and vigor long forgotten, perhaps never known. Another sip. The skin flic is their quiet place away from the street.

Huge bosoms loom from the screen. They sway a moment, then recede behind a narrow back, white bunched buttocks. Carefully entwined to hide their slumbering organs, the couple ruts mechanically. The sound track switches into fevered gasps, the same ecstasy sequence you’ve heard in the previous mating scenes. The camera moves closer; necrophilic pallor fills the battered theatre. The starers are mostly winos nursing their afternoon bottle. Fraternal, the derelicts pass their paperbags along the row for sips. Occasionally they remark on the action, comments about dominance and vigor long forgotten, perhaps never known. Another sip. The skin flic is their quiet place away from the street.

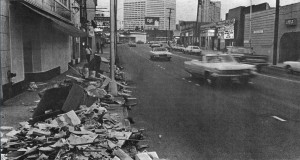

Stepping outside you glance toward Tenth Street, then north toward Colony Square. Where are the hippies, the runaways, the suspicious characters, the police, the curiosity seekers? Peachtree is deserted here. You could see more longhairs in downtown Dahlonega than on the famous Strip. You walk past vacant stores, interiors littered with refuse. Suddenly two bikers careen out of a bar, macho mutterings. Their steeds are nowhere to be seen. Lost somehow, they step away quietly.

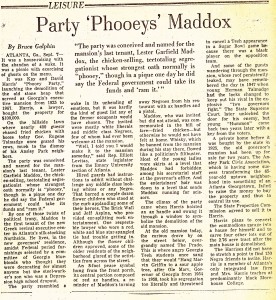

A handful of headshops are still open, but business is light, selections limited, merchandise touristy. Handlers of more genuine counter culture goods like the People’s Crafts Co-op, better known as the Laundromat, have folded. A few older stores, thirty and forty years at their locations, remain. “The Lt. Governor’s wife still trades with us and so do her children,” one owner reveals. A flash, of Virginia Maddox wedging her way through hips, blacks, the whole street melange to buy a dress. Most business people are cautious. “I never saw anything bad happen. I don’t want to say anything else.”

A handful of headshops are still open, but business is light, selections limited, merchandise touristy. Handlers of more genuine counter culture goods like the People’s Crafts Co-op, better known as the Laundromat, have folded. A few older stores, thirty and forty years at their locations, remain. “The Lt. Governor’s wife still trades with us and so do her children,” one owner reveals. A flash, of Virginia Maddox wedging her way through hips, blacks, the whole street melange to buy a dress. Most business people are cautious. “I never saw anything bad happen. I don’t want to say anything else.”

Food is the hot item these days. At the expanded American Lunch tidy secretaries chat over vegetable plates; a Third Battalion Fire Chief with the afternoon free grabs a bite before teeing off.

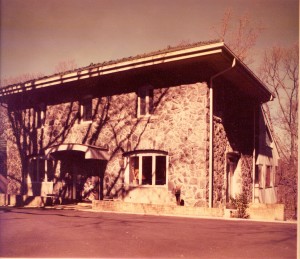

Franco’s near Peachtree and llth is booming. Baked goods, delicatessen items, lots of pizza—1500 a day sometimes. The interior is shopping mall slick, complete with TV camera that scans the well-dressed customers. Where do they come from? “Oh, Colony Square, 17th Street, even downtown.” Why do they come? “To get pizza made with the very best meats and cheeses,” Franco answers proudly. “And the dough is rolled each morning.” Locals? “Some.” Winos? “No drunks inside. They come to the window. They like pizza too. You try it.” I taste. It’s delicious: light layers blending into a fluffy crust. How long have you been here? “Two years, a little more.” You missed the real strip. “I guess.” What now? “I stay. Business gets better. Everybody likes good pizza.” He’s right about that. I wiggle out past a long line of pizzaphiles.

Maybe in five years Franco will have the pizza concession for another Colony Square. The Marta Station will be in around llth; the shotgun apartments, boarding houses, neighborhood stores will be gone. In their place will be office towers. Toward Monroe Drive refurbishments and condiminiums will house solid middle class. Perhaps some ex-hippies, by then forged into suitable work units, will toil in those new office towers. And sometimes perhaps they will search the streets below for a thread back to their carefree days along the Strip. But they will find little to break the seal on their now ordered lives.

No doubt about it, the Strip, Tight Squeeze, Tenth Street—darling of the media, bane of respectable people and their representatives at City Hall, mecca for small town rebels, slaughtering ground for criminals and carpetbaggers, stock market for illegal drugs, boardwalk for the lonely and very young—all this is gone. Already people have trouble remembering who was there, where the buildings were, the right year. “’68? That’s going way back. Ask across the hall.”

There was crime, but nobody really knows how much. Police statistics weren’t broken down geographically until about a year ago. “You could go through the case files.” How many for the years I want? “Half a million.” Narcotics either knows a great deal or nothing, for they talk in circles, generalities. Marijuana and cocaine are up; heroin, downs and acid off. Activity in a certain location? “Maybe. Hard to say. Could be. Don’t know.”

Crime, drugs and hippies—the three are interconnected when you mention Tenth Street. Yet to focus on these items alone is to miss a great deal about a subject that has much to say about Atlanta’s future as well as its past.

Fifty years ago the Tenth Street neighborhood was one of the better addresses in Atlanta. Stretching south to Ponce de Leon, and east along it were stately homes and townhouses, the domain of many of the city’s most respected and well-to-do families. In those days Buckhead was a relatively bucolic suburb; and Brookhaven was the country. City Council Chairman Wyche Fowler recalls: “I remember hunting only two miles above Buckhead as late as 1958.” Trolleys and electrified buses still trundled through the streets. The downtown skyscrapers were undreamed of. But in the fifties, Atlanta experienced an unprecedented boom in population and affluence. During that decade the metro area swelled some 30,000, half of which flooded Atlanta proper. By 1960 nearly half a a million people lived inside the city limits, a number that has grown only slightly since. There was room in the city then. Countless trees and houses went for apartments, service stations and eateries.

Like many parts of Atlanta, Tenth Street grew in population, but declined in aesthetics and property values. Peachtree was zoned C-3, Central Area Commercial, in 1953, while the areas north of 14th remained a hodge-podge of residential and apartment zonings on into the sixties. Most of the new residents worked: there were ties to the established community; but change was definitely in the wind. Cushman Corporation assembled its 11.6 acre Colony Square package in ’65 and ’66, applying for C-3 rezoning in ’67. By then the Arts Center was going up. Speculation speeded decline: more absentee owners meant decreased maintenance, less attention from city services. Other rumblings were afoot.

Spurred by cries for more education that had grown out of the ’57 Sputnik shot, colleges opened their doors to millions of young people. Then as now, these youths looked for a Rite of Passage to convey them from adolescence into full adulthood.

The twenties had prohibition; the thirties depression; and the forties war—all effective Rites of Passage. But in the fifties not even war was called war anymore. Society provided youth with vague symbols like drivers licenses and diplomas, but these only marked equally vague changes in status: there was no large, emotion ally satisfying demarcation between childhood and maturity. Perhaps this need prompted the Beat movement of the late fifties with its romantic rebel lion.

In the early sixties the cries about feelings that the Beats had stirred spread in the student world. First folk music and then rock emerged as highly participatory movements. Large numbers of young people were coming closer together in ideas and inner rhythms.

By 1965 a small underground of Beat/alternate life style people had built up in Atlanta. At the Commune near Emory, the Big House near Tech and the Georgia State student clusters around Little Five Points, fifty or more might show up for a party.

These people knew they were different, quite how they did not yet know. They could see that the usual collegiate success plan was not for them. And those who thought about politics saw that Vietnam would not do as a Rite of Passage either. It was simply an artificial death rehearsal for our dollar bloated legions.

About this same time strange new substances began to filter into Atlanta from Mexico, Texas and California. Peyote, mescaline and LSD opened up the head and gave a glimpse of incredible other realities. The only problem was that they were too distorting for everyday use. Something was needed that would loosen the chains that bound these seekers, while still allowing them to operate in the world. What about this marijuana stuff? They tried it, and Pow! The cannabis cyclone hit the country and things haven’t been the same since. Suddenly there was an easy divider to separate the sheep from the divine goats. Folks started feeling good in a way you don’t get on Old Crow, Mill town, and Norman Vincent Peale.

Suddenly they were in touch with a whole universe of sensation and in sight that had been lost by main stream white society. They were different now: they couldn’t relate their new consciousness back to the old community. It was too structured, anyway. For their Rite of Passage they needed a separate existence. Thus, the logical thing to do was to drop out of the old order’s schools and work, because their work now was this new community. In fact, the community itself was their Rite.

These are the people who first came to Tenth Street. They came to join the small colony of artists and leftover Beats who had already made bohemian landmarks of places like the Roxy Deli and the Palatzio apartments. Later they were called “true” hippies as opposed to the hoards of imitators and displaced persons who came after them. Many were artists who came to be near the Arts Center. Others were simply looking for some place cheap near their friends, and someplace equally removed from the city’s colleges. At last, a place to be themselves.

The first head shop/coffee house scene was probably Bo Lozoff’s Middle Earth off Peachtree on 8th which opened in ’67. In a prophetic gesture the cops were there the very first night, sizing up this new lunatic fringe. Soon they had more to inspect than they’d bargained for. The Catacombs at Peachtree and 14th revved up: then came the 12th Gate where, in addition to music, the clinic that later became part of the Community Crisis Center operated for a while. Bands began to play in Piedmont Park and concerts became a regular event. Performers like the Allman Brothers, Hampton Grease Band, Boz Scaggs, Joe South, Avenue of Happiness and the Grateful Dead filled a mile-wide space with sound, and the air around the bandstand turned green with hemp.

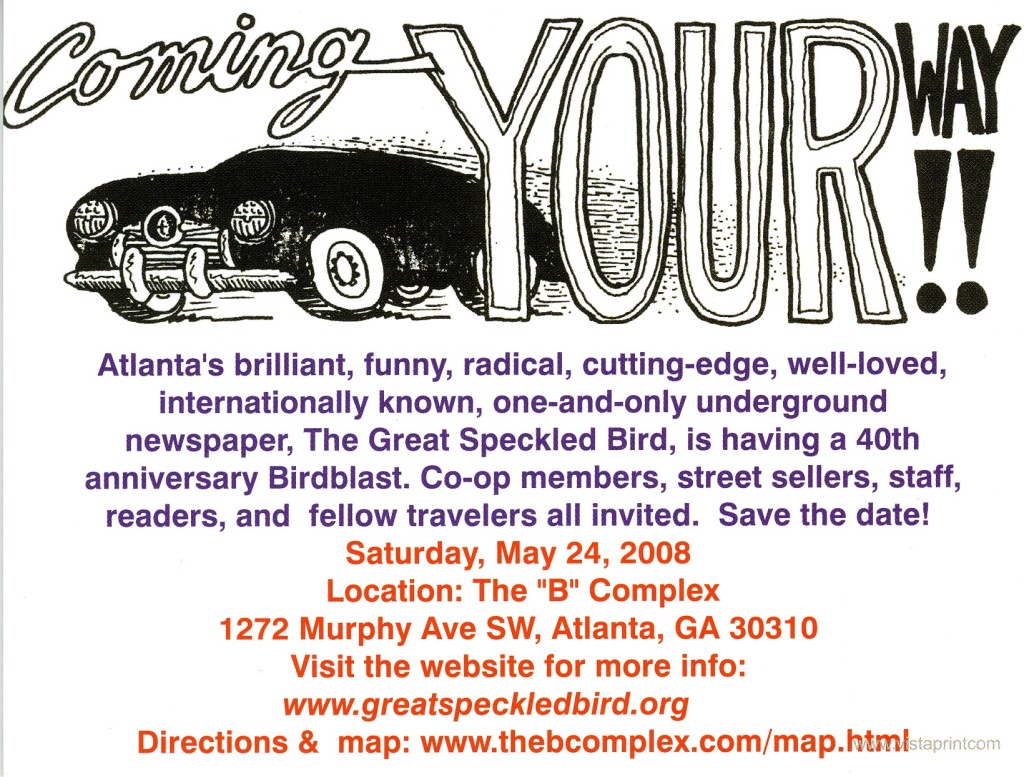

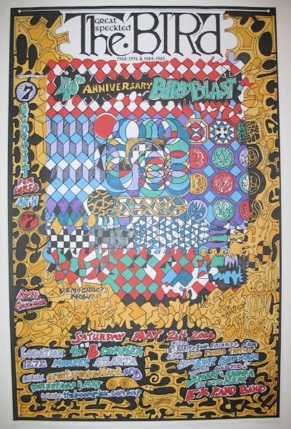

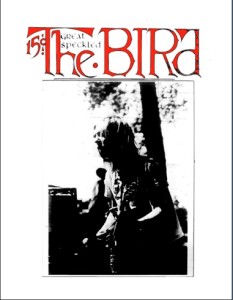

Expressing the growing sense of community, the Great Speckled Bird was started in early ’68. Now in its 7th year, the Bird had its roots in papers like the Los Angeles Free Press and the outspoken collegiate journalism that had gradually been driven off campuses in the early and middle sixties. The Bird didn’t bother so much then with reform of the old order: it was a glorious display of new self. The early issues were direct in formation sources for the culture then firming up. Articles appeared regularly on drug properties and responses, freedom of the press, crafts, semi-religious inspiration and community doings. Satire and togetherness pieces ran often. To pick up pocket money hippies began to sell the paper along Peachtree. From there it found its way into colleges, high schools, and onto young professional’s coffee tables, everywhere raising disquiet and recruiting converts.

Despite its then radical values, the Tenth Street community might have gone on quietly for years, a haven for artists and malcontents, but three faraway events forever changed the local idyll. There was some time lag, but rapid communications and the sheer fascination that these events held for the general public insured that Tenth Street as a genuine grass roots movement would die quickly.

First came Haight-Ashbury’s much publicized ’67 Summer of Love. Haight-Ashbury as an indigenous movement probably died like Tenth Street, before its greatest fame, but what came out of the Summer of Love, in song, truckin’ and heavy media, was a social gospel of drugs and free living that infiltrated the entire country.

Next came two mass gatherings: the May ’68 March on Washington was the more organized of the two, drawing its energy from war frustration and reaching back through the civil rights movement for its tactics. The other gathering was Woodstock later that summer. There the word finally got out. Young people every where felt the call and went spontaneously, nearly half a million of them. They learned on a mass scale that they could go, that they could come together and be high on music, drugs, sex, adventure. All you had to do was go. Hundreds of thousands who had never before seen a way out, or even known that they wanted out, suddenly got very restless.

What this meant for Tenth Street was a population explosion. The Strip soon began to look like a barnyard of exotic animals—bare skin, flowing manes, and the powerful smells and sounds of a close-together herd.

Actually, the Strip was a highly diverse collection of individuals, many of them quite intelligent and purposeful. Labels were made out of drug use, outlandish dress and supposedly freer sex, but the only real standard was non-conformity. What ever established society had expected the Strip people rejected. If family had counted before they would take only first names; if money had count ed, they would have none. Whatever established society hid—its massive drug use, promiscuity and discontent —these Strip people showed openly.

Individuality was respected: if you looked hard enough you could find freaks who never touched drugs. There was only one universal sin. Squealing.

From small towns all across the South kids swarmed to the Strip. Some stayed only a few weeks, then drifted home, their Rite needs satisfied. Others remained, suspended in their flowering time.

Many came to buy drugs. The underground network for illegal sales was not built up as it is today. Atlanta was one of the few places where drugs could actually be obtained. “Grass, speed, acid,” ventriloquist whispers came as you jostled in the crowd. “Scag, reds,” floated up from the curb. Larger dealers slept by day, venturing out at night, money belts jammed, to make connections away from the Strip. By today’s standards even the big dealers were small. A few pounds stash made you a neighborhood hero.

The Bird began to print advice about where to sleep or seek aid. Too young, too pampered, many of the new arrivals literally did not know how to take care of themselves. They didn’t recognize infection or malnutrition; they didn’t realize that rags can ignite or that rooms need ventilation. Everyone had extra people in their apartment: crash pads were jammed. The overflow slept in the parks or competed for abandoned buildings with the winos who had been driven out of downtown by Underground Atlanta. Outsiders sneered at the slovenly residents while landlords let water drain down onto the street. The city did nothing.

Stores, clubs and theatres opened:

Asterisk, Society Page, 10th Street Art Theatre, Percy Flasher, Sexy Sadie’s. Of particular interest is the Merry-go-round which came along in ’69. A young entrepreneur named Lenny Weinglass with a partner who has since departed, smelled money happening and threw their savings into the hip clothes store. Weinglass now runs 50 Merry-go-rounds out of Baltimore. Except for the Allman Brothers who were really a Macon band, Weinglass’ business growth is the only real traditional success story to come out of Atlanta’s flirtation with cultural pace setting.

There were other kinds of success however. For many the Strip provided a home. Raymond, a prison escapee from a neighboring state, was not a conventional dropout, but his story is typical. Bandied about in foster homes as a child, by the time Raymond made his way to the Strip he had spent half his 25 years in jail. On the Strip he found people who accepted him. Raymond never sold the Bird—too risky. He trimmed hedges and drove nails for spending money. He read a book or two, but he doesn’t read so well; mostly he listened, basking in the smooth vibrations. He backpacked a few times, and he painted a picture, not a bad picture for a beginner, lots of greens and open spaces. For a year he lived like a human being. Finally things got hot and he surrendered voluntarily. An other year in. Once out, confined to his hometown by parole regulations, skilless, jobless, pulled in on lineups, he’s awaiting trial now on his same old charge, burglary of a few dollars.

Angie is probably not typical either. But after seven years on the Strip she has seen it all. “I was seventeen; I had dropped out of high school. Later, when I went back I went straight into college.” Did you do drugs? “Sure, nearly everybody did.” How did you live? “I sold the Bird, I worked odd jobs. I never depended on a man, so I was better off than most women.” Angie never speaks of girls and boys on the Strip. “We were not children. We had left that behind.” How were you better off? “I never had to sell myself, or take crap from men.” Were many women younger than you? “Lots. There were thousands of runaways— thirteen, fourteen-year-olds. They could look older and get by.” Why were they there? “They were looking for something. Everybody was. We didn’t know what it was, but at least things were different than what we’d come from.” Why do you stay now? “It’s my home. So much has happen ed. It’s like my life began here.” Are you happy? “I think so. The important thing for me is other people.”

A new kind of weekender came by the thousands. Donning “hip” apparel, perhaps bought right on the Strip, these plastic hippies promenaded with the rest, hungry for mini adventure: a joint in the park, a cultish conversation, running from a cop.

Blacks were on the Strip in numbers too. They were mostly young men, searching for freedom and companionship that their own tighter, more traditional cultures could not provide.

Saturday night on Peachtree there was a nearly solid chain of body contact from 7th to 14th. Vibes raced up and down the street, throbbing like a single pulse. Dusty’s being hassled at the Krystal. Richard the Narc’s up at Jumping Jack’s let’s go to Grin’s and snort up. Watch out for the bikers they’re leaning on folks tonight. Bikers have always been around Atlanta. The Suns, the Huns, Iron Cross, more had come. Mostly Outlaws stopping off between their clubs in Kentucky and Jacksonville. Rugged, fiercely independent, many are also mean and tormented. They could and did mug, torture and kill. Some clubs maintained veritable arsenals, and they weren’t the only ones.

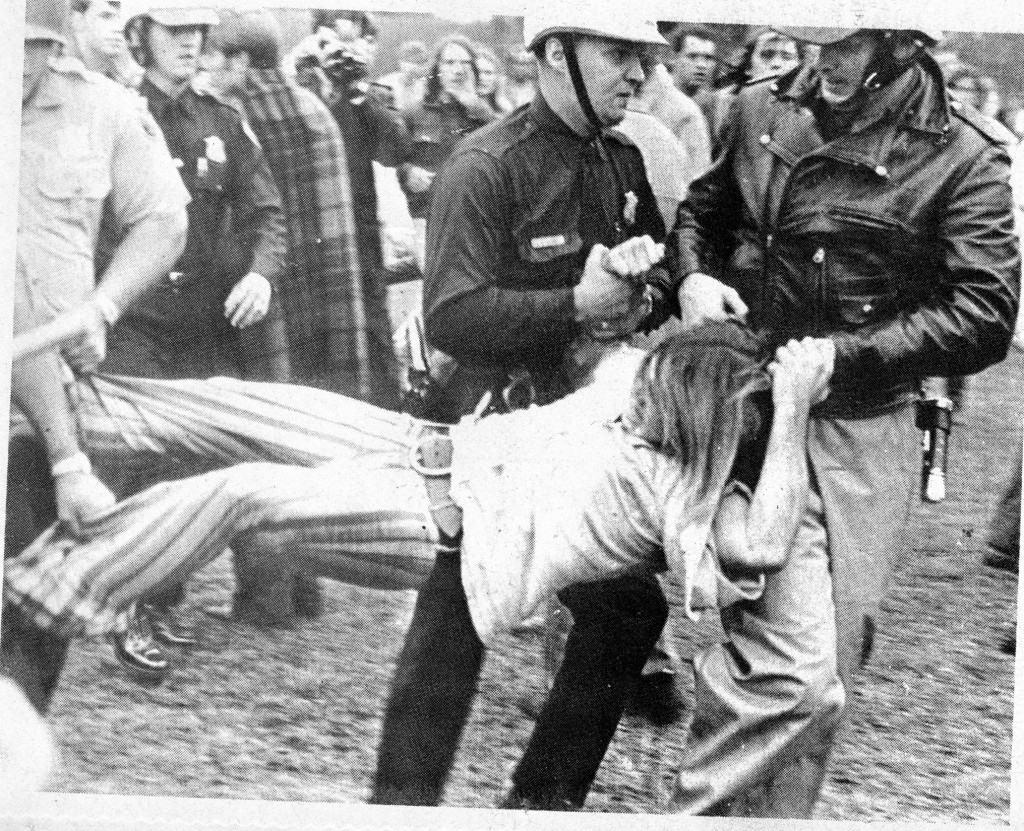

The hippies were by no means all gentle folk. The October ’70 riot between police and hippies grew out of hippie anger over biker harassment. The bikers got the word that night and stayed off the street, leaving a wound-up crowd that exploded when a cop attempted a street search.

Step right up. Hur-ray, hur-ray, see the Freaks. If you actually lived around Tenth Street then, you know what it was like. If you didn’t, no amount of description can give it to you. I lived less than five blocks away, but it was more like a light year. With friends I would saunter down on an evening to see the sights. Perhaps I was a more benign curiosity seeker than those Grayline Tours once proposed to bus in; more sym pathetic no doubt than those whose cars jammed Peachtree, gaping, and trying to pick up girls; gentler than the thugs who reacted to difference by assaulting with abandon on the side streets, but I was a curiosity seeker nevertheless. The excitement and carefree happiness made you feel good; you smiled, flashed peace signs.

Maybe my values were not that removed from these adventurers: the difference between us was one of risk. To live on the Strip, to trust on the Strip, to go home on it was to risk big. Someone might flip before your very eyes. People were still learning then how to handle themselves under drugs, and unscrupulous dealers would sell poisonous compounds. Mugging and rape were rampant and a lot of it went unreported. Worst of all you could be busted. Nobody knows how many people were arrest ed for possession or selling drugs on the Strip. However, Al Horn, at one time the only lawyer in town who would take a drug case says, “I must have handled 2000 such cases from ’68 to ’72.” Not all were as a result of Strip arrests. There’s no way of knowing the real tolls in money and time in jail Strip people paid for their community.

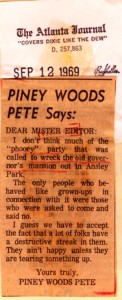

As early as ’69 Ivan Allen’s seek and destroy police tactics caught national attention. Then Sam Massll’s “Tight Squeeze” police precinct— the Pig Pen—came along in, was it ’71? Anyway it was there a while and then it wasn’t.

Who the officers and narcs were does not matter now. Some were sensible and did good jobs; some didn’t. How much serious crime against life and property the police prevented is open to question. Their presence often served only to heighten the paranoia that was always on the Strip in some degree. Even when fifty or more officers patrolled Peachtree U.S.A. from 8th to 12th you wonder if it was more a matter of visibility than real community protection. Peachtree, Juniper and Crescent were probably safer, but, in the shadows, crime went on with a vengeance. The hip organized Street Patrol, sixty strong, walked women home and generally helped out, but the volunteers were young and the patrol floundered after a few months.

Fire was a problem too: 7693 pumper missions during ’68-72 from stations II and 15, which serve the Tenth Street area. Poor living conditions and carelessness were definite causes, but arson was the real threat. Eventually the arson squad went to “Tight Squeeze” fires as a matter of routine. “We found so many gas cans we stopped picking them up,” one investigator said.

Rumors proliferate that developers were behind some of the flames, but there’s little hard evidence. Fires could be convenient for an owner too, especially when there are 5000 suspects milling around outside. Again, little evidence. Atlanta’s fire problems have not been confined to Tenth Street however. In ’68 alarms jumped nearly 25% city-wide and have remained high ever since. Diverse sections like Johnson Ferry Road and Fulton Industrial Blvd. showed just as heavy increases as Tenth Street. Although it has never fallen to pre ’68 levels Tenth Street’s fires have slackened somewhat. Alarms in other places are still climbing.

One theory has it that the concentrated police pressure drove true freaks away, ending the Strip. More likely the police were simply the most visible of several factors that made the area an increasingly undesirable place to live; population pressure, ever poorer housing, more business people to whom the freaks were merely the drawing card, ever more hopeless transients—destitute wanderers for whom Tenth Street was a brief stimulant in the midst of long, hopeless years. And finally the inescapable fact that the Strip was a Rite. After you have passed through, after you have stood on your own and survived, you move on.

Why young people chose to test themselves this way while others of their age group went quietly to war or the factories is a pointless question. They did, and in so doing they changed all of us. Their Rite was sometimes brutal, but anything less real might not have served.

The happening that was the Strip probably peaked in 1970. That summer you could scarcely pass on the sidewalk, and the Byron Pop Festival in July drew over 100,000.

If you could pinpoint a change from community to ghetto it might be December 29, 1970. That night Tree Me Sherry a hippie and a biker protégé drew a gun in a biker arsenal at White Columns on 14th and was double barrel wasted. Simultaneously, a few blocks away on Juniper Bruce Gwynn, a sightseer from Virginia, was being tortured by other bikers, his body later dumped outside the city. Two weeks later Chief Jenkins declared “Tight Squeeze” was “no longer a hippie community, but a stopover place for outlaws and criminals from all over the nation.”

Strip population always thinned in the winter. The hoards were there again in the summer of ’71, but not as dense as the previous summer. Group consciousness diminished. Now many were street-wise returnees, aggressively stalking the territory they had mastered. You saw more downs and heroin. Arson increased and there were fire bombings: Atlantis Rising went, then the ‘Bird’ office in ’72. The permanent Strip denizens were older, tougher. The hip stores were patronized by suburbanites and straight kids. As a matron might seek out Lenox, they came to Tenth for records and smokin’ papers.

The Crisis Center’s clinics handle hundreds of cases each month: their phone calls average over two thousand—almost none of which concern drugs anymore, but by previous standards their business is way off.

The Strip has been deserted by youth, and it’s now a dangerous place to be.

Except for rape, which is off a bit, 8th to 16th on Peachtree does a brisk business in murder, robbery, assault, car theft, any category you care to name. Throw in the side streets and you have nearly as much crime as Hunter, Capitol, Cascade, Ponce and Pryor streets combined.

This is an abominable situation that the new police administration should work to correct. Hopefully they will try some new approaches. However, illegal street searches have always gone on in the district: as recently as April of this year lawyers were protesting them. Aside from” being highly questionable constitutionally, the crime rate speaks for their ineffectiveness.

New development will undoubtedly diminish crime in the area. The lower income predators and victims will be pushed into some new pocket of the city. Ponce de Leon and Little Five Points are already shaping up as hot spots. But will this time honored urban practice actually lessen crime, or merely cordon it off?

Cultural dynamic change aside, the Strip was fated to be short lived be cause it stood on very attractive real estate. The Central Area Study pre pared under Mayor Massell tells the story plainly. There will be more office space, more hotels, less housing in the Inner Ring of the city. “Growth.. .is assured.. .if concerted efforts are made to keep the traffic flowing and to remove the barriers to the investment opportunities which will inevitably generate.” The Arts Center project, among others, was designed to provide “maximum development leverage.” Enter corporate planner, exit poor people. “Spot zoning started the Tenth Street area’s problems,” says Wyche Fowler. So you reach the inescapable conclusion that the offensive hippies were truly a windfall for a predevelopment neigh borhood.Already going to seed.

It has also been suggested that Atlanta’s uptight response to hippiedom stemmed from its own insecurity. Compared to other cities’ problems, Tenth Street was mild; and after ’69 it was almost all derivative culture imported from elsewhere. Atlanta should have loved that. Yet rejection was vicious and widespread. Perhaps a clue lies in our vast—estimates run as high as 70%—middle class. Atlanta has always been the great escape valve of the South. Generations have come as the street people did, to find bright lights and opportunity. A lot of small town folk have done well here. Perhaps the seediness of the hippies reminded too many Atlantans of their own pasts.

Where are the hippies today? Everywhere. Their Rite accomplished, they have gone to work and life styles as diverse as the ones they originally came from. Whether what they experienced was really different from the adventures of past generations cannot yet be answered. Neither can we know now how well their moment in the sun prepared them for their years ahead. Only one thing can be said for certain: it was a truly grand moment.

In the aftermath of the hippie phenomenon a question remains for Atlanta. As it seeks the pearl of “international city” status, will it learn to appreciate and to plan for the diversity that is the hallmark of great cities? Glamorous as Colony Square is, let’s hope the entire city doesn’t end up looking like this; and let’s hope that the next neighborhood where artists and new thinkers congregate Won’t end up a criminals’ and developers’ war zone.