In 1962 The area was hailed as

In 1962 The area was hailed as

“Atlanta’s own Greenwich Village”

Read it here.

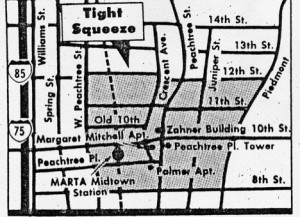

Thanks to High School student Trevor Alexander for researching Tight Squeeze, as the area was first called..

Peachtree Street near 10th Street has long attracted diverse travelers, even before it was Peachtree. There was a path following the ridge between Creek settlements at Suwanee and Standing Peachtree on the Chattahoochee. About 1813 local men upgraded the path into more of a wide trail. With this completed, Lieutenant George Gilmer left Fort Daniel, Hog Mountain in present-day Gwinnett County, traveled south on Peachtree Road and completed Fort Peachtree [Gilmer] on a small knob overlooking the Chattahoochee. Now the trail was first known as Peachtree Road.

At the time the fort was built this was the western edge of America’s frontier and not a part of the state of Georgia. The Creek ceded the land in 1821. In 1837 Western and Atlantic Railroad approved the location of the southern terminus of the railroad just south of Fort Peachtree on the Peachtree Road. Late in 1847, Atlanta, defined as extending 1 mile from that Terminus, was incorporated.

The Civil War touched the area directly. The Great Locomotive Race ended for Andrews and some of his raiders when they were hung at what is 3rd and Juniper.

During the Battle of Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864, both sides wanted to take the high ground, Peachtree Ridge, which Peachtree follows. Confederate troops fell back as far down Peachtree Road as the intersection at Ponce de Leon Avenue, where the Fox Theatre now stands. Union troops got about as far south as the area between Tenth and Eleventh Streets. Visualize that the next time you ride through the area.

Between 1865 and 1867 as the Southern states tried to recover from Civil War, Atlanta arose as the rapidly expanding new economic center of the Southeast. This attracted relatively large Jewish and black populations accentuated with people from virtually every state and many foreign countries, creating a more cosmopolitan city than any other in Georgia.

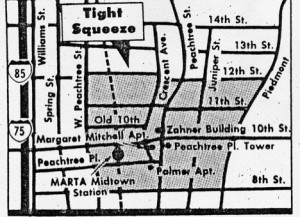

According to Franklin Garrett’s three-volume history of Atlanta: Atlanta and Environs, back in 1867 Peachtree, narrow, crooked and bordered by heavy woods, jogged sharply westward at the present Peachtree Place and followed what is now Crescent Avenue until returning to its present course at about 11th Street. It was between the town, which by then had inched north to around 2nd street, and the wagon yard around the present 14th Street, at the bend in Peachtree which is now 10th Street, that Tight Squeeze popped up after the war. It was a bunch of shanties, together with a black smith’s shop and several small wooden stores – beside a 30 foot deep ravine.

The ravine was thick with brush after the Civil War. It was a classic postwar period; desperate times. The hungry, the homeless, the wounded, the hopeless filled the city streets. The ravine became a rest stop to both freedmen and displaced Confederate veterans, some left morphine addicts. Just north of the ravine where Peachtree intersected a country road that’s now 14th Street, was the wagon yard, where freight was unloaded for the merchants further south in downtown Atlanta.

Merchants en route to the wagon yard on 14th with their pockets full of the “cash on the barrel-head” demanded by the freight companies, or merchants returning with wagons loaded with goods, slowed to skirt the ravine at today’s 10th Street. In the days before Flagship Merchant Services as a traveler slowed, it was the practice of residents of the ravine or real highwaymen to attack and grab or rob anything they could. It was said that it “took a mighty tight squeeze to get through with one’s life.” So the area acquired the name Tight Squeeze. Way outside of Atlanta at Tight Squeeze, desperation inspired rowdyism and a good deal of lewd vagrancy.

You can still locate Tight Squeeze today. Drive along Peachtree between 10th and 11th, notice that midway in the block the street is depressed. Where it is depressed was the lip of the gully. The lip was filled in for the street in 1887 when old Peachtree Road was straightened. If you look to the east, you’ll see that old hollow, that’s partly a paved parking lot now. The hollow goes all the way down to Piedmont. That was Tight Squeeze.

Many victims of Tight Squeeze did not make it through with their lives. John Piaster, a Confederate veteran, after selling a load of wood in Atlanta, was fatally knocked in the head there on Feb. 22, 1867. His attackers were not apprehended. Another victim, Jerome Cheshire, sustained life-long injury in a similar attack. Now a prominent citizen had been murdered and there was an outcry. The Fulton County Grand Jury, alarmed by the attacks, urged that a force of “sober, steady and energetic Secret Detectives” be set up to patrol Tight Squeeze and other approaches to Atlanta to protect travelers. Much as they set up the Pig Pen on Peachtree in the early 1970s.

Between 1870 and the 1890’s, other than postwar rebuilding projects, Tight Squeeze became the first urban renewal project in Atlanta. The area gradually improved as the suburbs of Atlanta crept north on Peachtree. Developers now wished to sell houses in the area, so it needed an image make-over. By 1872 it was renamed “Blooming Hill”. A man known only as Spiker, a citizen of Blooming Hill, wrote the local paper in 1872 that Blooming Hill is a “considerable little town,. . . with several fine dwellings, two grocery stores and another building”.

Just north of the city limits, then still around 6th Street, a group of rich Atlantans with an interest in horses had formed the Gentlemen’s Driving Club on 189.43 acres northeast of Blooming Hill. They subsequently formed the Piedmont Exposition Co. to hold a large 1887 Exposition on the club acreage, newly named Piedmont Park.

By then the residential area of Atlanta had reached Bleckley Road, now 10th Street. In preparation for the Piedmont Exposition, Fulton County filled in part of the ravine and straightened Peachtree to its present course, leaving the old course as a back street. The old Peachtree which had curved around Tight Squeeze was renamed Crescent Avenue.

The success of this fair prompted the Piedmont Exposition Co. to buy most of the acreage which was to become Piedmont Park from the Gentlemen’s Driving Club. Several more fairs were held on the land until plans began for the major 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition. There were exhibits by six states and special buildings featuring the accomplishments of women and blacks. On opening day, September 18, military bands played, followed by speeches from political, business, and other leaders, including the prominent African American educator Booker T. Washington. In a speech that came to be known as the “Atlanta Compromise” speech.

The midway was at 10th Street and Piedmont.

In 1894, the owners of the park offered to sell the land to the city of Atlanta for $165,000.00, but Mayor John Goodwin refused. The park, therefore, remained in private hands for ten more years outside Atlanta city limits and taxes. Meanwhile the land between the park and the central business district began to grow as a residential area, undoubtedly aided by the 1900 extension of streetcar lines to Fourteenth Street along both the major traffic arteries of Peachtree and Piedmont. This encouraged development along the northern blocks of both roads. During this time, the park was the site of major and minor recreational activities and a magnet for growth. State fairs were held in Piedmont Park and celebrations on July 4th and Labor Day. Atlanta was always more progressive than the surrounding areas. The Piedmont Exposition Co. opened a special section for African-Americans including a “comfort station.” At this time, most city parks were much more strictly segregated.

In 1903 George Washington Collier died and his undeveloped land, 202 acres west of the park and north of the city, was sold and subdivided in 1904. The main developer was Edwin Ansley, who created the Ansley Park subdivision along guidelines set by Frederick Law Olmsted. Thus the streets were a curving maze with large open spaces or “mini-parks.”

The other major event of 1904 was the renewed offer by the Piedmont Exposition Co. to sell Piedmont Park to the city — this time for $160,000. Mayor Evan Howell favored the purchase, but only if annexation included those developed areas adjacent to the park. This would add approximately $35,000.00-$40,000.00 in tax revenues annually and provide justification for the park’s purchase price. In the end, Atlanta paid $98,000.00 and acquired an improved tract of land, complete with roads, sewers and drains, water facilities, fair buildings, and a baseball field. In 1904 Atlanta’s city limits were extended from Sixth Street all the way to 15th Street.

“It’s a shame what happened to this part of Atlanta; almost everything I knew is gone,” says Dr. Bernard Wolff as he peers down Peachtree Place, his childhood stomping ground. “I was born right under there in 1909,” Wolff says, pointing to modern slabs of the Southern Bell switching office, next to the Midtown MARTA Station. The site used to be occupied by the Wolff family’s seven-bedroom Dutch colonial house, until he sold it to AT&T in 1962. All around were the mansions and maples of Blooming Hill. “Look at that big magnolia tree beside the telephone building. I’ll be darned; it’s still there.”

Wolff recalls his neighborhood as full of trees, mansions and children. “Tenth Street School, which is long gone, was the best grammar school in Atlanta. Ask Franklin Garrett, he was in the class ahead of me.” The Wolff family kept a cow in a nearby pasture. “My father, also a doctor, always complained the milk was bad because Sherman infested the grass with daisies.” Wolff played baseball in a field north of 979 Crescent Ave, The Windsor House, later known as “The Dump.” The house was built as a single-family residence in 1899. In 1907 the original family moved to Druid Hills. Years later the house was divided into the Crescent Apartments.

Urban Atlanta continued its northward movement. In 1911 the Georgian Terrace Hotel at Peachtree and Ponce had its grand opening. It immediately became known as one of the finest hotels in the Southeast.

In 1913 on Peachtree Street the homes and mansions of the wealthy were still prevalent. Ansley Park, northwest of Eleventh Street, was the new suburb for the city’s elite. Apartment houses proliferated in the areas between.

Yet eleventh Street was only developed from Peachtree to Piedmont and that was paved only with rubble. Although sewerage went all the way to the park, water ran only to Piedmont Avenue as late as 1918. Perhaps due to this lack of development and services, the section of Eleventh Street from Piedmont Avenue to the park became the site not for luxury apartments but the decidedly middle class Piedmont Park Apartments. These were designed by one of Georgia’s first woman architects, Leila Ross Wilburn.

In 1924 the new governors’ mansion is opened at 205 Prado in Ansley Park cementing its place as a leading address for Atlanta’s elite. A new clientele for the area merchants emerged.

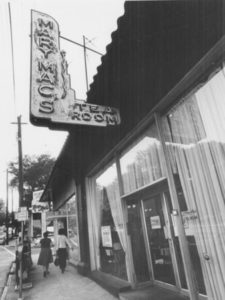

The secret of Tenth Street’s early success was the independent “quality minded merchant.” The area became famous for the place where you could get the best of everything in what had become a unique “village” type atmosphere. “Remond’s” French Restaurant or the King Hardware Store that carried most everything; Knights and Baldwin’s purveyed the finest in produce, and Mr. Reed delivered tons of the finest meats to Tenth Street’s prize clientele Roxy Delicatessen was Atlanta’s original “Spaghetti House” and the greatest sandwich in town was their bill of fare. Bennie Kaplan and Davis Ajouelo were fine craftsmen making repaired shoes good as new. There were many more fine merchants—too numerous to mention—during Tenth Street’s “Golden Era.” During that time Tenth Street was the place to eat, live and shop for Atlanta’s elite, from the Governor’s family of the day to the wealthy dowagers complete with chauffeur driven limousines. In this period, people from Paces Ferry, Garden Hills and Morningside enjoyed the area.

Margaret Mitchell parent’s home was near the village around Tenth Street, the nicest shopping area in Atlanta. Everybody walking or hauling their groceries home in their arms or those little carts. The stores were busy and interesting, and the streets were fragrant with bakery smells from King Cole bake shop and rich delicatessen aromas from the old Roxy. It was called Atlanta’s Greenwich Village.

“Tenth Street was a lady, a good-looking, viable retail center sort of like Lenox Square today,” recalled Franklin Garrett. “There seemed to be at least two of everything. Bank branches, hardware stores, 10-cent stores, butchers, bakers, florists, dress shops. Fruits and vegetables were displayed outside, at that grocery stores, which were individually owned, while inside, mature clerks with pads waited on the matrons, charged their orders and had them delivered. The Hemlock telephone exchange, a fine, cream brick building erected in 1916, is now a U.S. military processing station. The Roxy Delicatessen had the best sandwiches in Atlanta. The Universal Garage was well patronized, but it was converted to the Hideaway, a Dixieland jazz club. The Tenth Street Theater was pulled down when they widened 10th west of Peachtree.”

Grown-up Margaret Mitchell wrote for the The Atlanta Journal Sunday magazine, Her book, Gone With the Wind, would not be published until 1936. Located in what was then Atlanta’s largest business district outside of downtown, close to trolley lines, and walking distance from her parents’ house, the Crescent Apartments was home to Margaret Mitchell and John Marsh when they married in July 1925.

The 1920s were unstable financial times and had an effect upon the area. Crescent Apartments’ owner became over-extended, and the building was sold at auction in 1926. The next owner, too, was driven to bankruptcy when the stock market crashed in 1929. Maintenance declined, contributing to Mitchell’s characterization of their apartment as “the Dump.” By the fall of 1931, there were only two occupied apartments in the building, one of which belonged to the Marshes, but they, too, moved to a larger apartment a few blocks away in the spring of 1932.

In 1926 Mrs. H.M. High donates her home to Atlanta on the condition it become an art museum which opened in October. This would make the area a point of focus for the artistic, a trend that began when the artisans who had created and performed at the Cotton States Exposition wished to live as near to their work in the Park as possible.

In 1929 The Fox Theatre, a place of the performing arts and the motion picture, opens. Vaudeville on Peachtree.

“My first knowledge of the Tenth Street area came in September of 1937,” says Jack Hazan. “My father opened a business there, and I candidly felt that he might have a rough time making it out there in the ‘country’. He made it, and we were in that same store until November 1970. From the four or five stores located in the Tenth Street Shopping District in 1937, the area grew to be Atlanta’s first major shopping center away from the Central District; at one stage during the ’40’s the Tenth Street Merchants Association boasted a membership of close to 100 wholesale and retail business outlets.”

From 1946 to the early 1960’s, the area continued as a prime location to live or shop. A large percentage of Atlanta’s female support staff, secretarial, clerical, and medical, lived in apartment buildings near the Peachtree and Piedmont trolley lines which gave easy access to downtown. They called it the 10th Street Business Section, and—“taken together with 13th, 14th and 15th streets immediately to the north—it’s as near as Atlanta comes to having its very own Greenwich Village, Soho, Chelsea, Left Bank, or whatever other big cities call the collective digs of their avant-garde citizenry”.

The city’s high schools ended their gender segregation in 1947. Tech High and Boys High combined to became still active coed Grady High, while Girls High became coed Roosevelt High, now The Roosevelt apartments.

Modern new shopping centers and parking took their toll. The 10th Street area began a decline in August 1959 when Lenox Square mall opened with 47 shops. The sophisticated aura of the new shopping area farther North on Peachtree began to sap customers from the areas between and beyond. The handwriting was on the wall for the charming Village of Tenth Street, Georgia. Vacancies began to appear.

The clarion of events to come was a several page announcement in 1964 that a shopping center called “Ansley Mall” with plenty of customer parking and modern stores of all types would soon be built, and would open a scant couple of miles from 10th at the gateway to one of its “mainstays,” the Morningside Community. This proved to be a crucial blow to the underdeveloped area in the center of downtown Atlanta, the old commercial district on Peachtree Street between 8th and 14th. Merchants concurred that business volume dropped a good 20 to 30 percent when Ansley Mall opened. The shopkeepers had made a feeble, but futile attempt to offset this by operating a parking lot in what remained of the ravine in the rear of some shops; it helped some, but it was not enough. The downward trend continued. Next came the removal of parking meters and an almost complete ban of “on street parking” in the area. As if this were not enough, Tenth Street, Piedmont and Fourteenth Street were made “One Way.” This sure helped to move traffic! —away from and around the Tenth Street district.

The clarion of events to come was a several page announcement in 1964 that a shopping center called “Ansley Mall” with plenty of customer parking and modern stores of all types would soon be built, and would open a scant couple of miles from 10th at the gateway to one of its “mainstays,” the Morningside Community. This proved to be a crucial blow to the underdeveloped area in the center of downtown Atlanta, the old commercial district on Peachtree Street between 8th and 14th. Merchants concurred that business volume dropped a good 20 to 30 percent when Ansley Mall opened. The shopkeepers had made a feeble, but futile attempt to offset this by operating a parking lot in what remained of the ravine in the rear of some shops; it helped some, but it was not enough. The downward trend continued. Next came the removal of parking meters and an almost complete ban of “on street parking” in the area. As if this were not enough, Tenth Street, Piedmont and Fourteenth Street were made “One Way.” This sure helped to move traffic! —away from and around the Tenth Street district.

Along Juniper, 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th streets, modern apartments blend with old homes converted to boarding houses or apartments which have served, and are serving, generations of Atlantans. If one were a sociologist, he likely would find that young high school and college graduates, during the 60s and 70s, coming to Atlanta to seek their fortunes gravitated naturally to the 10th Street section due to its artistic aura, its reasonable rents, convenience of transportation and shopping facilities. For those not yet ready or willing to accept a sentence to staid suburbia and the eternal lawn-mowing chore, the 10th Street section is a welcome means of escape. The 10th Street section was a vital, throbbing, essential part of Atlanta—culturally and otherwise.

Unfortunately the Georgia surrounding Atlanta was much less enlightened. Lester Maddox, wielding gun and ax handle, chased blacks from his Pickrick restaurant on Northside Drive near Georgia Tech in early July 1964. The following month, Maddox closes the restaurant after being ordered to desegregate under the U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding non-discrimination in public accommodations. Maddox then started a petition campaign for mayor, but was easily trounced by Mayor Hartsfield who was reelected to a sixth term.(Maddox in front of Grady High demonstrating his ability to lead Georgia into the future.)

Maddox decided his constituency was outside cosmopolitan Atlanta, so in 1966 he ran for governor. Although Bo Callaway, one of the first Republican members of the United States House of Representatives elected from Georgia since Reconstruction, won a plurality, he lacked a majority and the Legislature picked Lester Maddox as governor.

The new Governor seemed at odds with the city. Atlanta is a metropolitan city. It had always been in the forefront of civil rights and progressive action for a southern city, as well as any in the country. It had a history of being a political anomaly. Peachtree Street was more than a romantic connotation. Atlanta is a symbol of everything Maddox was not. Spiritually Atlanta was more akin to San Francisco and New York than it was to Birmingham, Alabama. Another point was that by the 1970s San Francisco and New York had become more the land of the “put on” and the “putdown” than the real thing. But in Atlanta there was a whole new generation of hippies, Southern youngsters bearing small resemblance, except by name, with the hippies of fun and frolic who occasionally paraded nude through the streets of the San Francisco. In Lester Maddox Georgia, it could be dangerous to be too flamboyant around the wrong people. Keep that freak flag furled till you reach 10th Street and Peachtree or Fourteenth.

The new Governor’s Mansion on West Paces Ferry Road opened in 1967, with Lester Maddox as its first occupant. West Paces Ferry Road replaced The Prado as the seat of culture. Around the park area even more large houses, and even embassies on 14th Street, become available to rent. Some are rented informally or communally and further subdivided. People rented a room to their friends and rents became even cheaper. Some of these homes served as salons for the free discussion of arts and ideas. These small groups of bohemians began to reach a critical mass and began to be aware of each other and interact.

When the hip thing first started, the old Atlanta neighborhood of Tight Squeeze or Blooming Hill, and environs, was a congregating place for hips idling on the corner. The scene was called the Strip by hip inhabitants as self-deprecating humor that the hip part of town was still small town, small time. The original hips created the Strip — intentionally or unintentionally — as a meeting place for sharing their culture, but it gradually expanded beyond their needs, and beyond their control. As more people of different stripes were attracted to the area, they added their own characteristics to the basic ones, causing the mutations which eventually drove out the early community members.

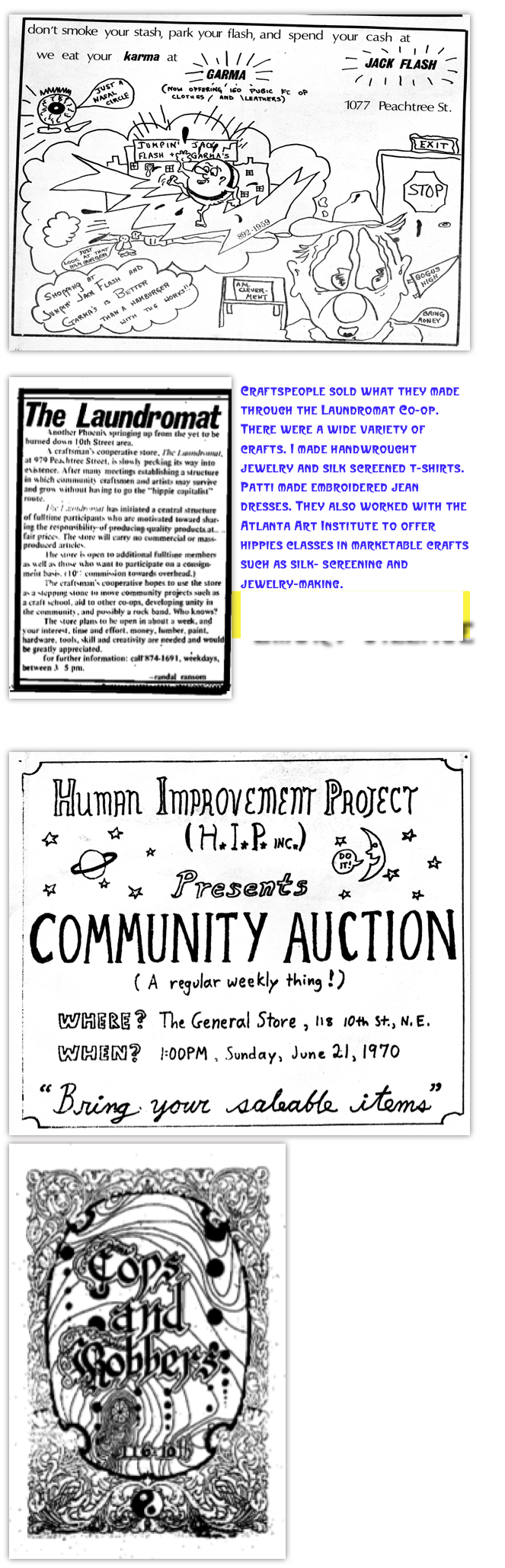

The next era was a hectic and tempestuous time in the area. Down from Fourteenth Street, out of deference to more progress , the Colony Square Project, came the Bohemian, hippy, flower children. Colorful boutiques sprang into being, and the vacant stores were filled with a new breed of merchant that cottoned to the urges of the new generation. There was sporadic violence as the streets teemed with people, and the phrase, “Wall-to-wall people” applied very well to what took place at what was now called “The Strip.”

Chances are if the hippies had come to Atlanta with money in their jeans, the reaction might not have been all that violent. The one great equalizer, above and beyond all else, is the economic reality of life. Former Congressman Charles Weltner, whose liberal point of view stood out like the Southern Cross, at the time commented sardonically, “There just, ain’t no percentage in hippies if you’re a businessman.”

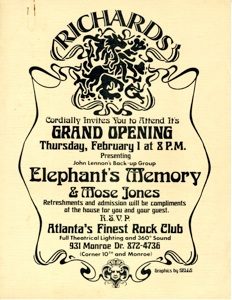

March 8, 1969 Underground Atlanta opened as Atlanta’s Bourbon Street, the all-hours fun location. Many of the hip community, especially musicians, welcomed this as a dependable source of income. Civil Rights and white flight shifted the sociology of Atlanta. The establishment in Atlanta officially shifted in 1969 when Sam Massell becomes the first the Jewish Mayor of Atlanta with Maynard Jackson, a Black, was vice mayor. That year Black aldermen increased from one to five, and Benjamin Mays, mentor to Martin Luther King, was elected to the Board of Education.

The hippies had made an incursion into the city and the neighborhood. They opened their own stores only to have them burned and looted. Time magazine reported the first bombing of a leather craft store owned by Susie and Ron Jarvis. As Time reported it, “When Ron complained to police (there were 27 bullet holes in the front of their store), he was arrested for shooting back. Says Ron bitterly: ‘We’ve got a new n-word in our society, and the way to tell him is by his hair and his beard.'”

In 1970, the flowering of the hip area reached full bloom. By June 1971 it is a several block stage show, played free of charge to a drive by audience almost nightly with extremes every weekend.

It is un-choreographed and undirected, the cast changes every night and none of the performer’s is given any lines to read.

Yet for more than two years it remained near the top of the entertainment list for Atlanta residents and their guests. When visitors came to the city, someone was sure to take them, or at least recommend that they go, to “The Strip.”

Like some of the other less conventional forms of entertainment in Atlanta, it received constant attention from the city’s law enforcement agencies. So much attention, in fact, that the police become regular members of the cast, taking on roles as vital to the show as those of the longhairs in the sometimes comic, sometimes tragic drama played there nightly.

But, strangely enough, most of the people responsible for this highly successful, long running show were no longer part of it. Many say they no longer enjoyed the performance and ceased to go on or near the stage. “Too many hassles!”

These young men and women, who through their searching for new horizons developed the characterizations and costuming for the show, now described the scene they left as “sick,” “dying,” having “bad vibrations” and being “nothing but a wholesale drug market.”

Law officers helped to make it unpleasant. The hippies were arrested for everything from breaking municipal jaywalking laws to reciting incantations of the devil. Raids were held with Gestapo like precision on homes where there was a suspicion of drugs. Furniture, possessions and walls were unapologetically smashed in some “searches”. They occurred with such frequency that calls and cries of harassment were heard from the once quiescent residents of an otherwise vital metropolis. Hippies were sprayed with Mace, whose use was then not generally approved.

As far back as 1969, a rock concert was proceeding at a relatively peaceful level when a cop, reacting to some thing less than a kind remark drew his service revolver. The wife of a professor at one of the nearby colleges tried to calm him. She was clubbed for her troubles, taken to a hospital in handcuffs and had six stitches in her head for her efforts. The war had begun!

Police began to stop strollers in the parks, using more force and indiscretion than any ‘stop and frisk’ law would permit. Piedmont Park which had changed from a native paradise to a homosexual hangout, was the focal point of picture taking by police who wanted to build a mug file of the new groovers. Remember homosexuality was still illegal in Georgia then.

The Police did not harass everyone coming in the area. The police had a particular fascination for ignoring the clean-shaven bands of vigilantes who had taken it upon themselves to beat up the out-of-towners. These ‘skinheads’ went after the hippies with all the zest of a lynch mob.

Hippies were shotgunned by these marauding vigilantes. Beaten and bruised hippies were jailed for disturbing the peace when they tried to report the crime, sometimes being told they had just got what they had deserved. One longhair was arrested for bleeding on the officer when he tried to report a beating.

You can speculate on the reason, but while Police vigorously pursued people with marijuana and psychedelics, many ignored hard drug dealers who very openly set up shop along the sidewalk on 11th Street. Wonder why the Police looked the other way?

After the hippies, and the ensuing deluge, the streets of the Flower Children got real mean, Strip joints, hard drugs, death and mutilation replaced the head shops, the funky little coffeehouses and the leather craft stores. There was a significant difference in the character of the Strip by 1973 as contrasted with the sense of community and purpose it had once had.

“A year ago,” says Bruce Pemberton of the Bridge, the area’s runaway mediation center, “I could spend five hours on the Strip, rapping the whole time. Now I can walk down there and literally not see a person I know.”

The Strip then seemed populated largely by runaways, transients, part-time hippies, and drug dealers. A visitor to the area rarely ran into the sort of young person who talked about an intellectualized search for alternative cultures; as used to be the case, instead there seems to be mostly people who parrot catch phrases about “the establishment” and the “‘pigs”.

Some disagree with this assessment. “I still think the same kind of kid that came down to this area four or five years ago and got involved in the community is still coming down, and that’s the tragedy of it.”

“It’s a business out there,” says Dennis Doherty, director of the Community Crisis Center, the agency that works most directly with the street people. “A lot of people wouldn’t be out there if they weren’t working — dealing (drugs), crafts, or spare-changing (panhandling).

Doherty says some of the seekers still come to the area and volunteer to work in one of the several agencies handling Strip problems. But when these people are absorbed into the highly structured system of agencies, they cease to be true street people.”

“It got pretty tawdry during the hippie era. They weren’t just peddling the Great Speckled Bird [underground newspaper} on the streets. You couldn’t walk 20 feet without somebody trying to sell you drugs or pot”.

“After the hippies pulled out, we had our fire age,” says an area resident. “Everywhere you see a vacant lot or a pocket park, there was a major fire in the late 1970s. Speculators would buy a building leased by a TV repair shop or a go-go club and two weeks later, the place would burn down. Very mysterious. But some of us tough cookies held on and made improvements.”

The police started building bridges to the rest of the community. As part of a trend that was taking place in many of the major cities of the country, their new attitude was one of trying to understand, ”or at least communicate with the community. And if hippies happened to be members of the area, communicate with them too. Rap sessions took place between people who were once throwing bricks and tear gas canisters. The thugs eventually found other rocks to crawl under and for 10 years, and more, Tight Squeeze was on hold. Cha Gio, Theatrical Outfit, Brother Juniper’s and some gay bars kept it alive.

While the new cast members play before the hundreds of automobiles cruising slowly by, the original or early characters are seeking new scripts for their lives—and the scenarios they are choosing usually exclude the high visibility inherent to The Strip. Many hips—especially those who set up housekeeping—moved away from Tight Squeeze and its problems. Throughout the middle stretch of Atlanta, there are hip families and generally they make good neighbors. The reasons for this diaspora are manifold and intertwined. They include police pressure, drugs, publicity and the changing nature of the people involved.

The underlying purpose of the Strip also seems to have changed. What started out as one specific facet of the alternative culture of the hip movement in the area appears to have become an end in itself to the newcomers to the hip scene.

Today the Strip lies in something of a limbo state: The larger hip community seems to be abandoning the struggle to keep the street life going, while no new leaders rise from the crowd to take up the battle flag cast aside in the retreat.

THERE ARE exceptions to the charge of abandonment. Earlier staff members of the Great Speckled Bird, an underground newspaper in Atlanta, staged a “loiter-in” demonstration on the Strip to protest the great number of arrests under the “Safe Streets and Sidewalks” ordinance.

For about two and a half hours the Bird staffers loitered on the sidewalk wearing picket signs announcing “We ain’t doing nothing” and “I’ll stay out of your way if you’ll stay out of mine.” The police stood by and watched and there were considerably fewer arrests that night.

But participation in the demonstration by the street people was less than enthusiastic. While the pickets were there, a few Strip regulars stood talking, remarking how pleasant it was not to have to “keep moving” or risk arrest. Later, however, when the demonstrators had gone, the situation returned more or less to normal, and few obvious loiterers were noted among the street people.

On another night there was an arrest of several young people in a car in the alley behind the Strip. As is traditional, a crowd of street people swarmed angrily toward the bust. talking about resistance and riot.

In the past, similar scenes had sometimes developed into vigorous resistance as the affronted hips banded together to protect their own. This time though, when a single portly policeman strode purposefully toward the crowd and growled, “Move it out,” the longhairs quietly scattered and went back to strolling along the Strip.

The seekers of three or four years ago brought a kind of coherence and purpose to street life, mostly in their efforts, to put together agencies to deal with problems.

Those of today, however, tend to move directly into established programs, and their abilities are directed not toward creating unity as much as toward solving individual crises.

The Rev. Greg Santos, cofounder of the Bridge, recalls that when he came on the scene the most binding activity was the drive to form the helping agencies needed in the area — the crisis center, the runaway facility, temporary housing for transients, and so forth.

Now these are organized and operating, most of them stable in their concepts if not in financing or staff. Santos suggests there is little left for the original “movers and shakers” to do, so they are leaving.

Some people within the hip community go so far as to suggest that if the crisis center and Aurora, a church-sponsored recreation center on the Strip, were not offering the services they do, the street people would not remain.

Doherty, on the other hand, says the removal of the agencies might actually bring back some of the lost leadership in a renewed effort to bring stability to the Strip.

No one can predict the future of the street life in Tight Squeeze, the historic name for the Peachtree 10th Street area. In 1968 it was announced that the Strip was dead and that there would be no more hippie community, but that forecast was quickly proved mistaken. ”

In a sort of hibernation since last fall, the Strip now is rebuilding its population with the increase in summer travelers and school vacationers. The tourist trade is beginning to pick up. Daily arrests are at a higher level than last summer when there was a special police precinct set up to deal specifically with the area.

The hip community leaders who have left the Strip and who now lack confidence in its ability to survive seem not to consider one possibility: That others could develop into leaders just as they once did, and as others before them did.

It is not impossible that a new “generation” of community organizers could spring from the street people this year, or next, independent of the older community which is moving on to new pursuits.

It seems unlikely, on looking at the apparently aimless character of the street people at this moment. But that could change with the influx of a new group of highly motivated young people.

Dennis Doherty describes the Strip as a “phase in the hip way of life. The question is, are the motivated, sincere newcomers going to feel it a necessary phase in their own development?

Like the land along Peachtree Street’s seamy “Triangle” area, Atlanta’s other major adult entertainment strip—Peachtree from Eighth Street to 12th Street—is owned by some of the city’s most prominent citizens.

The owners of the property all say they rent to their controversial tenants because there are no other takers for the premises. “I hate the fact that we’ve got to rent to that kind of establishment,” said Massell. “But at the same time we’ve got taxes and loan payments.

“If you leave a building vacant they (winos) come in and burn down the block. And so nobody wants it. I’ve owned that property since 1950. We’ve produce stores. We’ve had delicatessens. We had a first-rate neighborhood shopping center.

“But when the hippies moved in— you saw what happened. Many people were afraid to go down there.

1986 In 120 years, this colorful Peachtree-l0th Street district of Midtown Atlanta has evolved from a perilous bottleneck known as Tight Squeeze in the 1860s to a charming residential neighborhood named Blooming Hill in the 1880s to the tony 10th Street shopping area of the 1920s to the hippie- jammed Strip of the 1960s and early ’70s.

Garrett, Franklin. “A Short History of Land Lots 105 and 106 of the 17th District of Fulton County, Georgia,” Atlanta Historical Journal, Vol. XXVII #2, 39-54.

Garrett, Franklin. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events, Athens: University of Georgia Press,

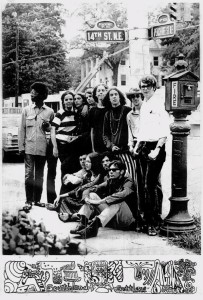

Lendon Sadler is the black guy on the left (Lendon went to San Francisco and was a member of The Cockettes.) , Fifi Fiuk next to him, then Charlie, then me (Lisa Deadmore), the guy next to me was a good friend but his name has slipped, Stevie Parker next to him, don’t remember the name of the guy next to Dee (his cousin), Dee McCargo, another Steve sitting down on the left, brother to the guy next to me whose name I’ve forgotten, the girl was part of the speckled bird staff, can’t remember her name, Gil next to her, and don’t remember the name of the other guy – everybody always through he was a narc!

Lendon Sadler is the black guy on the left (Lendon went to San Francisco and was a member of The Cockettes.) , Fifi Fiuk next to him, then Charlie, then me (Lisa Deadmore), the guy next to me was a good friend but his name has slipped, Stevie Parker next to him, don’t remember the name of the guy next to Dee (his cousin), Dee McCargo, another Steve sitting down on the left, brother to the guy next to me whose name I’ve forgotten, the girl was part of the speckled bird staff, can’t remember her name, Gil next to her, and don’t remember the name of the other guy – everybody always through he was a narc!