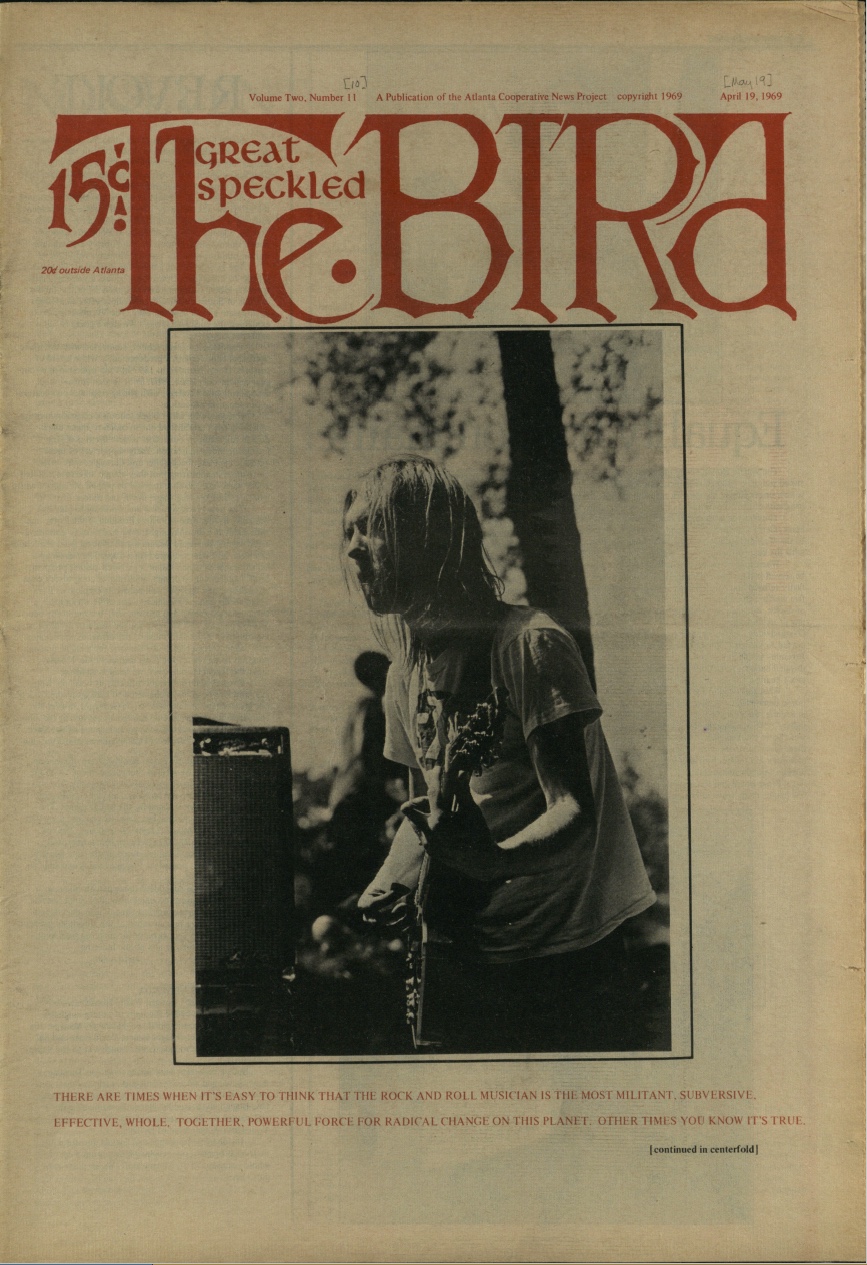

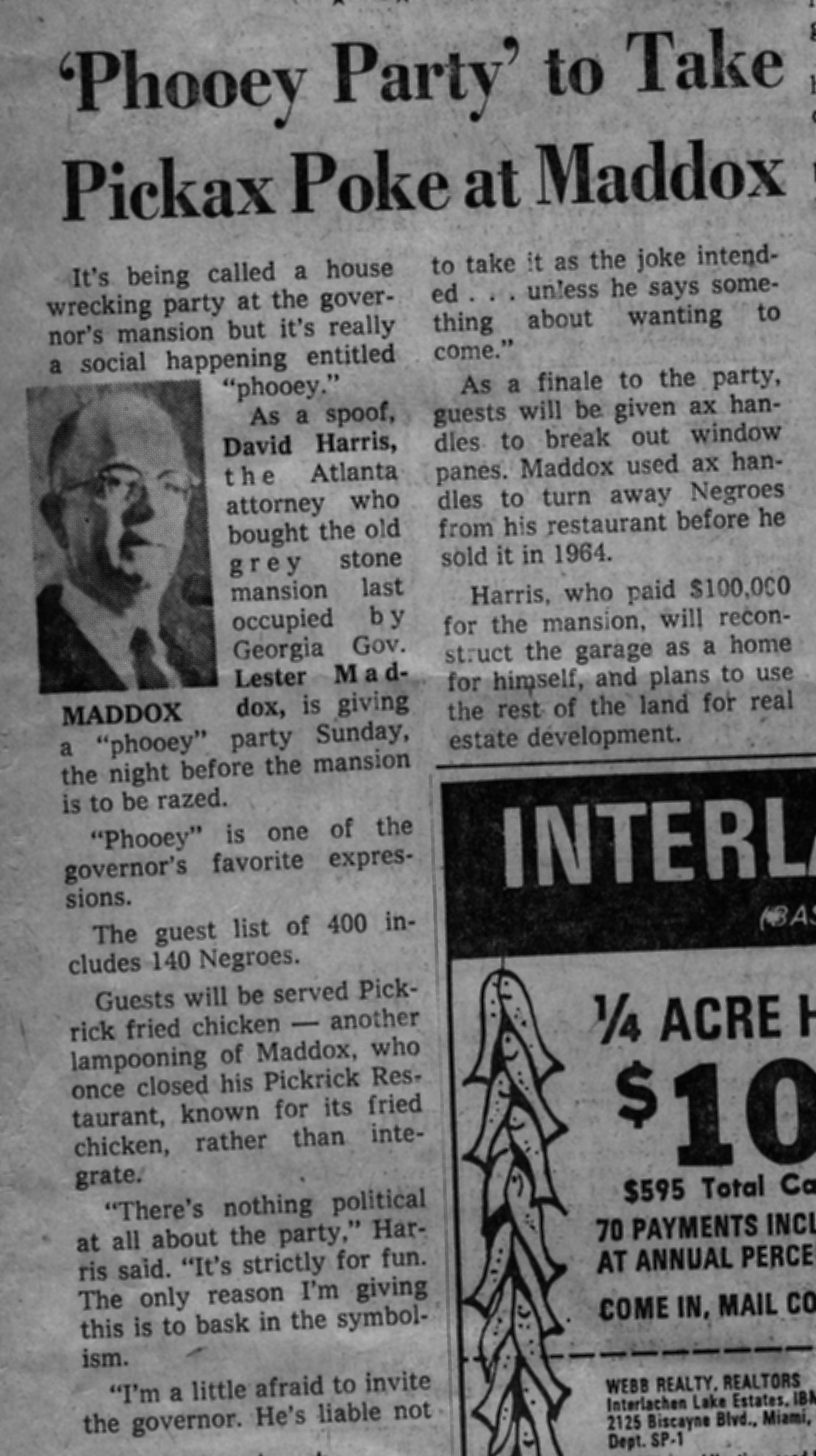

A Personal story of May 11, 1969.

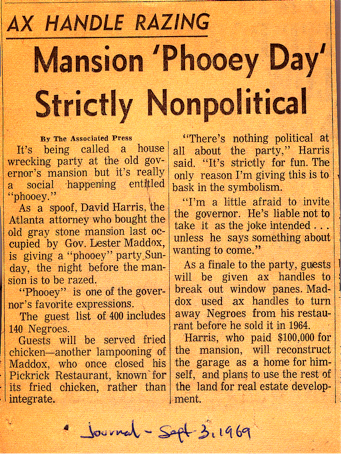

Upon first seeing the Allman Brothers Band, an interracial rock and roll band from the heart of segregated, reactionary Georgia not only calling themselves brothers, but acting like it, Miller Francis of The Great Speckled Bird put Duane on the cover with the words: “There are times when it’s easy to think that the rock and roll musician is the most militant, subversive, effective, whole, together, powerful force for radical change on this planet; other times you know it’s true. “

Georgia State University’s Library has this issue of the Bird available as a pdf. here.

The Great Speckled Bird

Vol 2 # 11 April 19, 1969

by Miller Francis

The Allman Brothers play a form of what some might want to call “hard blues” but that term merely relates their music to what we already recognize and accept as valid; it says nothing of their real achievements. What informs their creation is not black music but the experience of young white tribesmen in experiencing black music. After all. Ray Charles, and what he means, is a crucial part of the lives of this new generation of non-blacks. Thus black music can be approached creatively by our musicians if the jumping off place is our experience of that music rather than the music itself.

Quote of the Week:

Quote of the Week:

Policeman, after complimenting Barry for getting together such a pleasant, orderly crowd, “You can stay in the park all night for all we care.”

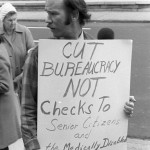

A leaflet drawn up by our “leader” says “Last week we were attacked. Some of us were shot. We were jailed, the culprits have not been caught The police did not and have never protected us” yet the same self-appointed “leader” personally takes it upon himself to represent the community by asking “permission” from the same power structure which exploits us, permission to listen to music which belongs to us, permission to meet together in a park which also belongs to us! The Man can’t bust our music. -don’t count on it.

Definition of MUSIC AS POWER. A perfectly straight middle-aged man stood near the band in the park Sunday, mesmerized for two hours at sounds which took him places he never knew existed. After the band took a break, his remark, more than a little unconvincing even to him as he said it, was, “That’s just a lot of noise. ” He knows things he doesn’t know he knows, and the character of our generation is determined by just those things.

Rock & Roll, our New Music, is sound for the head and body, orchestrated, electric, cosmic music that will rip you up by your corporate America roots and set you down just inside the Gates of Eden outside of which, we’ve known for some time now, there are no truths. You don’t, can’t, “listen” to the Allman Brothers; you feel it, hear it, move with it, absorb it, you “let it out and let it in” (the Beatles) and enter into an experience through which you are changed. You catch a glimpse of the kind of world we are becoming and you know more than ever the horrendous load of bullshit we’ll have to drop off on the way in order to give birth to that kind of world.

Rock & Roll, our New Music, is sound for the head and body, orchestrated, electric, cosmic music that will rip you up by your corporate America roots and set you down just inside the Gates of Eden outside of which, we’ve known for some time now, there are no truths. You don’t, can’t, “listen” to the Allman Brothers; you feel it, hear it, move with it, absorb it, you “let it out and let it in” (the Beatles) and enter into an experience through which you are changed. You catch a glimpse of the kind of world we are becoming and you know more than ever the horrendous load of bullshit we’ll have to drop off on the way in order to give birth to that kind of world.

A rampant fear of the mythical dragon of “Communism” (a la J. Edgar), nourished and fed by the power structure, flows throughout the hip community of Atlanta like a poison fragmenting us, blocking any efforts at organization, and our self-appointed “leader” holds up an SDS button, and says, “I transcend this.”

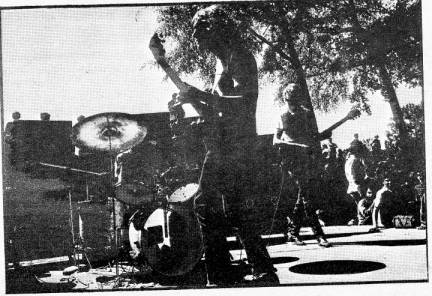

THE ALLMAN BROTHERS

THE ALLMAN BROTHERS

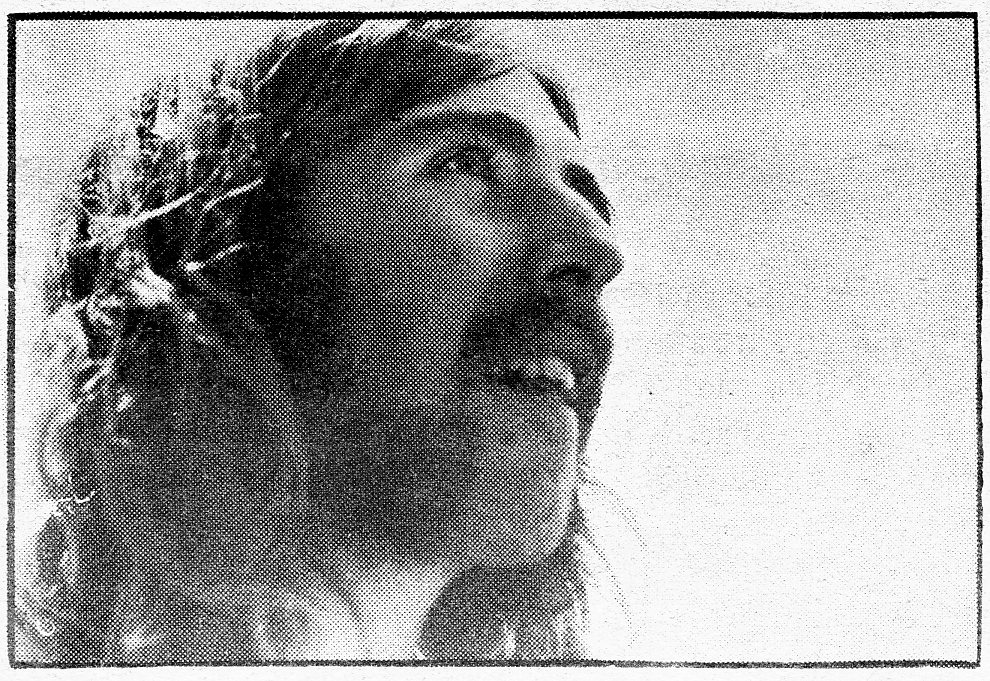

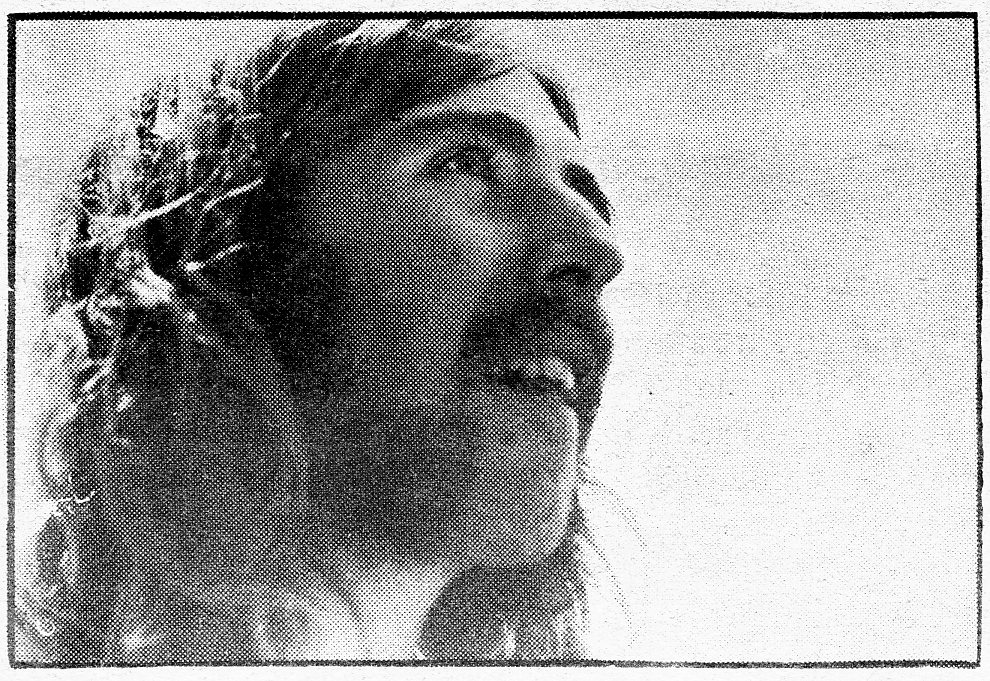

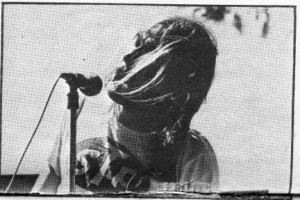

Duane Allman-Guitar & Vocal

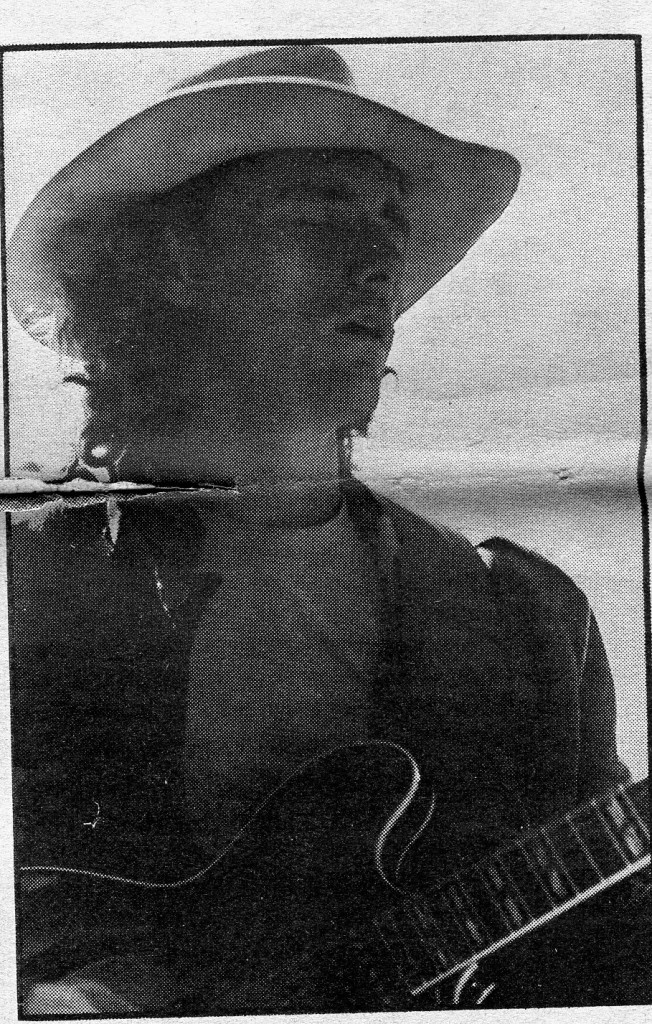

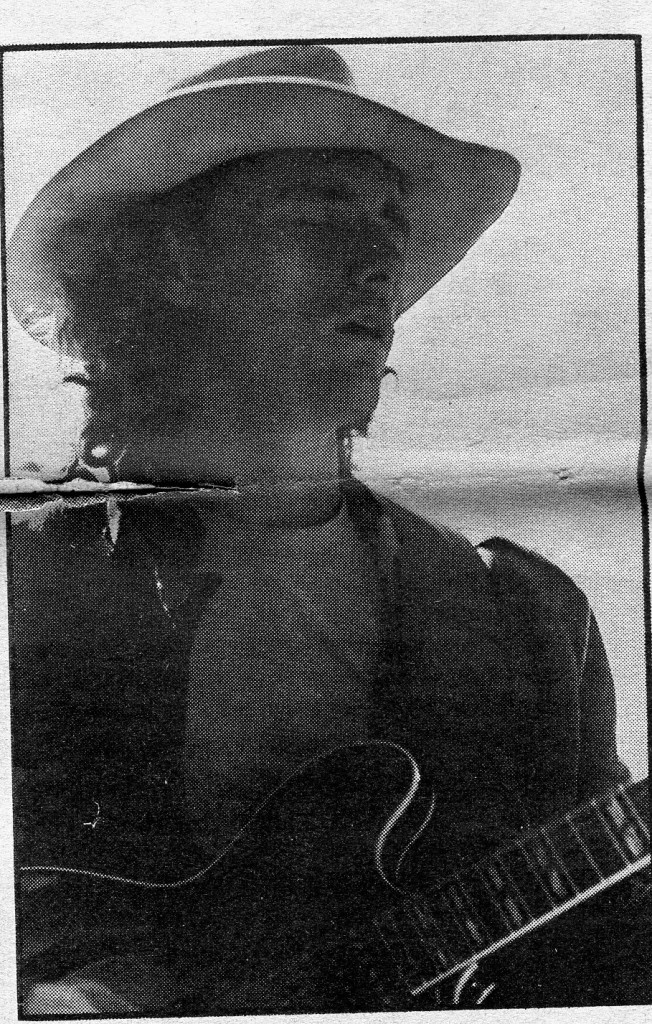

Gregg Allman-Lead Vocal & Organ

Berry Oakley-Bassist

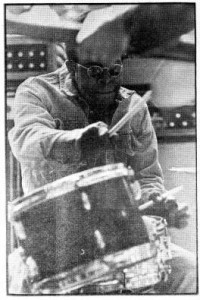

Butch Trucks-Drums

Dickey Betts-Guitar

Jai Johnny Johnson-Drums

Class prejudice the whole “redneck” concept—destroys the community from within, rendering it impotent, and our “leader” organizes us around contempt for the working man.

The Colony 400 monster rises in our very midst, attempting to determine how we will live our lives, and our self-appointed “leader” tell us hat “fear” and “paranoia” are our only enemies.

The Allman Brothers from Macon, Georgia, are a fantastically together group of young rock and roll musicians whose music draws as heavily from the blues: as the experience of young white tribesmen can without exploiting its source—a few steps farther and you get a merely talented farce like Johnny Winter. Since our generation is tribal, totally unlike our parents and grandparents and their parents, it is only natural that we would turn to the black man, whose tribal roots go so much deeper and do not have thousands of years of bullshit “civilization” to cut them off from these roots, for forms with which to relate to the new world.  The history of the black man in America is the history of tribal man in an alienated, fragmented, capitalistic, literate, industrial, “I”-oriented culture; young people are simply showing good sense when they attempt to co-opt black culture (just as the dying order desperately attempts to put its stamp on the culture of its youth)—but creating and redefining our own culture in terms of the new space-age tribalism is the crucial struggle and follows as naturally from where we are at now as Grace Slick follows Patti Page. The blues, the entire complex of music which has come out of the experience of the black man in America, belongs to forms and patterns and relationships to experience of which we now have only the tiniest fraction of an inkling (even that is a hell of a lot). The black man’s blues (whether manifested in Lightnin’ Hopkins or Smokey Robinson and the Miracles) flows out of him while our “blues” is wrenched out bloody like a prematurely pulled tooth.

The history of the black man in America is the history of tribal man in an alienated, fragmented, capitalistic, literate, industrial, “I”-oriented culture; young people are simply showing good sense when they attempt to co-opt black culture (just as the dying order desperately attempts to put its stamp on the culture of its youth)—but creating and redefining our own culture in terms of the new space-age tribalism is the crucial struggle and follows as naturally from where we are at now as Grace Slick follows Patti Page. The blues, the entire complex of music which has come out of the experience of the black man in America, belongs to forms and patterns and relationships to experience of which we now have only the tiniest fraction of an inkling (even that is a hell of a lot). The black man’s blues (whether manifested in Lightnin’ Hopkins or Smokey Robinson and the Miracles) flows out of him while our “blues” is wrenched out bloody like a prematurely pulled tooth.  Contrast the shouting subtleties and the rock- like soul of a Mahalia Jackson with the strained histrionics of a Janis Joplin (who, somewhere down under her package, probably does have some soul of her own). Art is not a product, it is a process: the blues—whether country or urban, acoustic or electric, raw or commercial -cannot be copied from records or concerts or books on black culture. The musical language of the black man cannot be co-opted simply because it happens to be powerful and sings of things we are just now recognizing as more valid than what we have been hung up in for centuries. Our music must develop its own power, its own forms, its own patterns of relationship with our tribal roots and our space-age technology in an unbroken line all the way down into our preliterate origins and all the way out into unknown galaxies.

Contrast the shouting subtleties and the rock- like soul of a Mahalia Jackson with the strained histrionics of a Janis Joplin (who, somewhere down under her package, probably does have some soul of her own). Art is not a product, it is a process: the blues—whether country or urban, acoustic or electric, raw or commercial -cannot be copied from records or concerts or books on black culture. The musical language of the black man cannot be co-opted simply because it happens to be powerful and sings of things we are just now recognizing as more valid than what we have been hung up in for centuries. Our music must develop its own power, its own forms, its own patterns of relationship with our tribal roots and our space-age technology in an unbroken line all the way down into our preliterate origins and all the way out into unknown galaxies.

The Allman Brothers know all this, and a lot more.

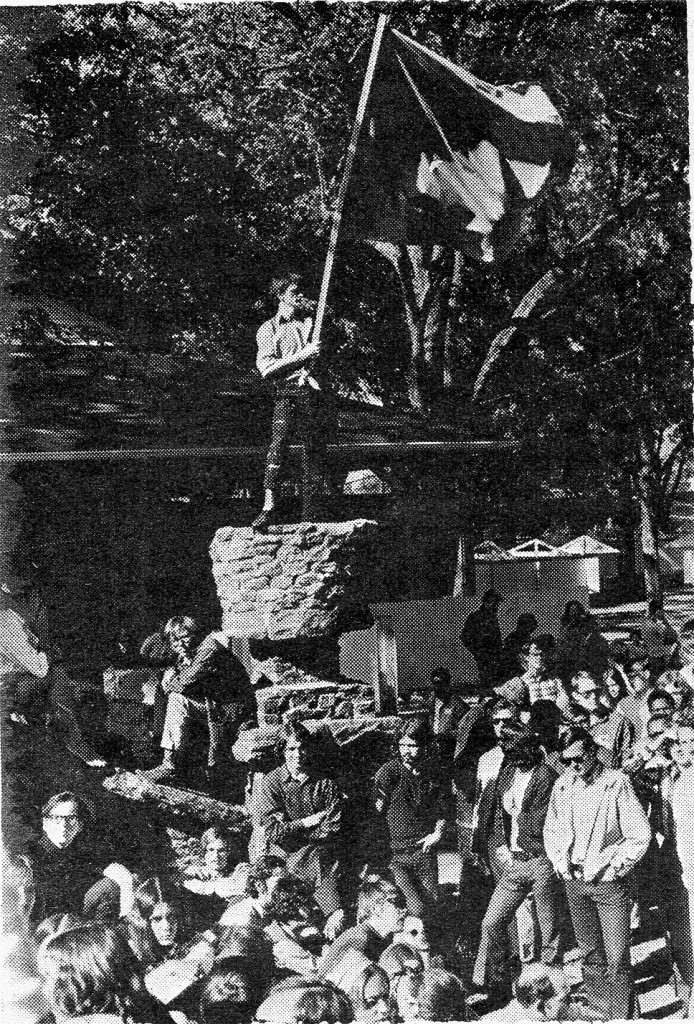

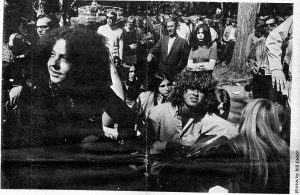

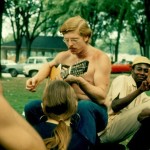

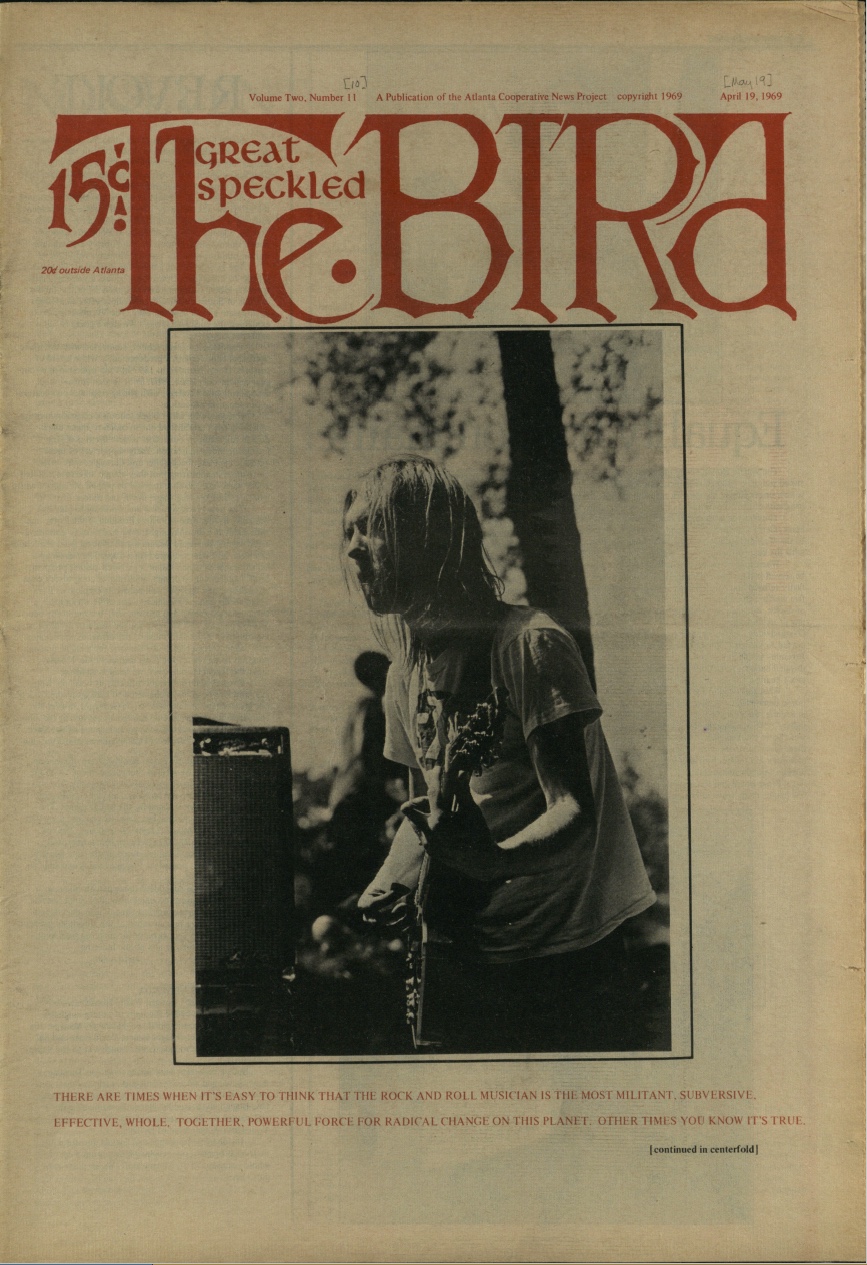

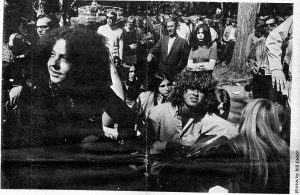

What we find in Piedmont Park on Sundays is a celebration of the awareness of the tribal experience. It in no way resembles the mass media bullshit image of the Haight-Ashbury community of “hippies” living like stoned zombie children off the sweat of others; it is an integrated collectivity of many different kinds of people intermeshed in an unbroken psychic web that transcends class, color, age and sex, and makes all of these things meaningful only within the context of the struggle to crush the power structure that stifles all of us.

The “political” manifestation of the Sunday Piedmont Park experience undid everything the music had built up. The sounds produced a together, militant, upright, powerful group of people involved in a psychic community struggling to become physical, to become “political” in the largest sense of the term. The politics of the “open” microphone is the equivalent of a band in which only a “lead” guitarist is amplified-it belongs to the past along with “teachers” and “employers” and “managers” and “leaders.” If we must have raps with our music, let them be unamplified groups planning whatever action they deem necessary. If hundreds of tribalists get sufficiently turned on, each one on be his own open microphone.

The “political” manifestation of the Sunday Piedmont Park experience undid everything the music had built up. The sounds produced a together, militant, upright, powerful group of people involved in a psychic community struggling to become physical, to become “political” in the largest sense of the term. The politics of the “open” microphone is the equivalent of a band in which only a “lead” guitarist is amplified-it belongs to the past along with “teachers” and “employers” and “managers” and “leaders.” If we must have raps with our music, let them be unamplified groups planning whatever action they deem necessary. If hundreds of tribalists get sufficiently turned on, each one on be his own open microphone.

The Merry-Go-Round exudes an odor of capitalist shit that you can smell all the way down in the park, and we are told by our self-appointed “leader” that our enemy is “violence.”

Capitalism the logical extension of the word “I” exploits the life style of our movement and our current self-appointed “leader” attempts to organize his own ego trip.

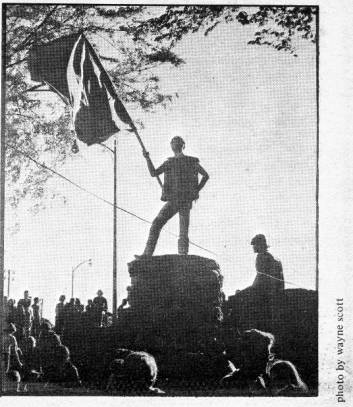

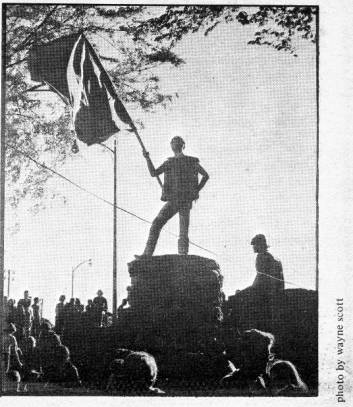

The only happening at the park Sunday which approached the power and the glory of the music was the waving red flag, another nonverbal experience which colored the events of the entire day and night.

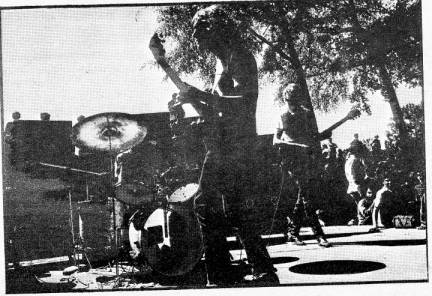

UPS: The tribal altar of Piedmont Park-stone pillars on either side of a two-stage stairway, level after level of people, sitting on the grass, on the steps, on the pillars, with the band, behind, in front, on all sides, across the top outlined by sun and sky, milling around, surrounding and enveloping and being enveloped by the music in an unbroken web of tribal psyche, sun, trees, grass, grass, music, animals, man woman and child all vibrating as one out of tune with die seats of established power and in tune with other communities wherever our music is being played

One together person reading Cummings’ “I sing of Olaf” to an overwhelmed audience unused to hearing those most militant statements—

“I will not kiss your fucking flag”

“There is some shit I will not eat”

Black saxophonist coming out of the crowd to jam with the band

New tribesmen passing their own version of the peace pipe

Phil Weldon rapping gently but forcibly about the red flag blazing above the stone pillar

Angry interchanges between Barry Weinstock and members of the community at midnight Sunday when it became obvious to everyone that spending the night in the park would accomplish not one fucking thing for anyone except those who dig spending the night in the park with the blessing, approval and “permission” of their city “fathers”

The power structure takes policemen out of our community and sends them into black neighborhoods to do their rotten thing and gives us our very own detective to soothe our ruffled white middle class beautiful gentle people (i.e. non- violent) feathers, and our self-appointed “leader” leads us to believe that we have won a great victory.

DOWN OF THE DAY-Barry Weinstock asking the band to stop playing so he could go into his rap!

The most subversive manifestation of the power of our music is its ability to weld an entire park full of every type of person from all walks of life into one, throbbing pulsation of experience.

Georgia State University’s Library has this issue of the Bird available as a pdf. here.

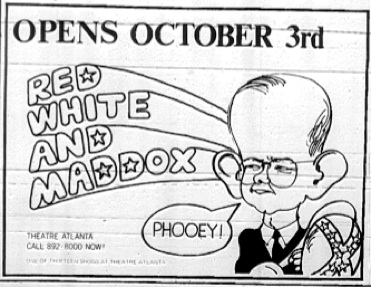

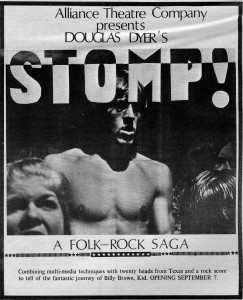

Atlanta theater has been dying a painful death for the past several years. And Atlanta audiences have been suffering from cultural deprivation. But Michael Howard, director of the Alliance Theater is taking a step to improve the situation.

Atlanta theater has been dying a painful death for the past several years. And Atlanta audiences have been suffering from cultural deprivation. But Michael Howard, director of the Alliance Theater is taking a step to improve the situation.

The Bird wails: “Atlanta theater has been dying a painful death for the past several years.” But hail the new hero: Michael Howard comes. Stomp in hand. offering a mixed-media novelty.

The Bird wails: “Atlanta theater has been dying a painful death for the past several years.” But hail the new hero: Michael Howard comes. Stomp in hand. offering a mixed-media novelty.