http://www.greatspeckledbird.org/

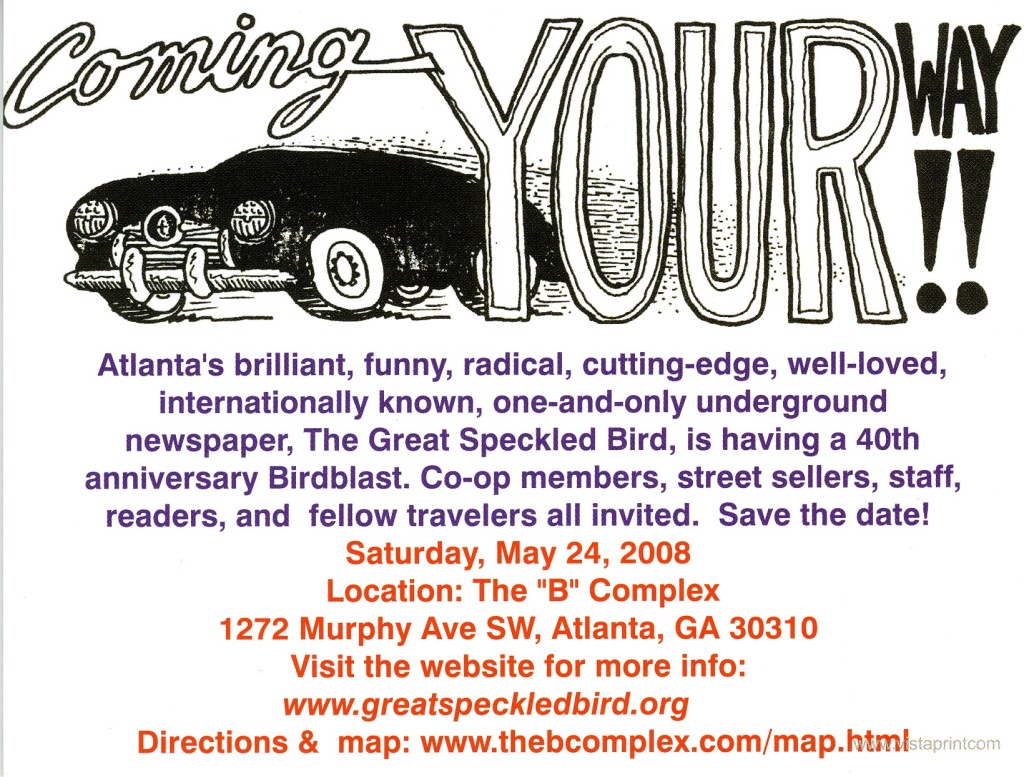

The Great Speckled Bird held a gathering of the tribe in May 2008.

Flock plans to celebrate paper that soared from underground

By Keith Graham Staff Writer

Hatched with a hopeful chirp by a flock of space-age muckrakers, it soared into flight 20 years ago billing itself as “The South’s Standard Underground Newspaper.”

With revolutionary relish, the Great Speckled Bird swooped from controversy to controversy the next several years, calling out for peace and racial justice and the making of a counterculture in an offbeat manner that attracted more readers than any other weekly paper in Georgia. But the self-proclaimed “anti-war, anti-racist” newspaper plummeted and crashed in 1976, its wings clipped by lack of enthusiasm in times that were a’changin’.

Gone but not forgotten by a generation that found it groovy if far-out required reading, the Great Speckled Bird will fly again if only for a day on Saturday, ironically the start of a weekend of memorials to victims of war, including a war the Bird firmly opposed. Ex-Bird “readers, sellers, writers, staffers and all beings of this known universe” are invited to a reunion doubling as a benefit for Radio Free Georgia (WRFG) and The Fund for Southern Communities at the Atlanta Water Works Lodge.

In traditional laid-back fashion, the’ event’s organizers say they do not know exactly what will happen, though there will be some music and an exhibit to remind folks of the gory glory days. “Hopefully, we won’t have riots,” said a chuckling Tom Coffin, who created a forerunner of the Bird — The Emory Herald-Tribune, later called the Big American Review — during a brief stay as an Emory graduate student.

Coffin, 44, a crane operator who came South after earning a degree at Oregon’s Reed College, and his wife, Stephanie, an activist from the University of Washington, were among the 20 to 25 founders, mostly white civil rights activists, who chipped in $25 to $100 a head to create the Bird in March 1968. They borrowed the paper’s name from a country song recorded by Roy Acuff, which in turn had borrowed from a passage in the Bible’s book of Jeremiah about a bird different from the others.

On the inaugural issue’s front page, Coffin spelled out the philosophy. The Bird, he promised, would “bitch and badger, carp and cry and perhaps give Atlanta (and environs, ’cause we’re growing, baby) a bit of honest and interesting and, we trust, even readable journalism.” It also would offer alternatives to the American way of life for “turned on” readers.

The other front-page story in that issue set the tone for what was to come with a blast at Ralph McGill, one of the icons of Southern moderation, even liberalism. “What’s It All About, Ralphie?” attacked the early civil rights advocate for becoming a “leading exponent of U.S. imperialism and deception” by backing the Vietnam War.

In subsequent issues, the Bird told its readers about the Black Panthers, Ho Chi Minh, the drug bust of local hippie Mother David and striking garbage workers. Readers saw regular coverage of theater, art and music, too. Not just the music of acts such as the psychedelic Vanilla Fudge and mellow Donovan, but even bluegrass and country. I

The Bird arose at a time when ‘ underground newspapers were flapping their wings from Berkeley, home of the Barb, to New York, where the East Village Other and the Rat were the rage.

Robert Glessing, author of “The Underground Press in America,” estimates there were 456 underground publications by 1970.

A minimum of 1.5 million people read the undergrounds by 1972, according to Laurence Learner, author of “The Paper Revolutionaries,” and other estimates put the figures as high as 18 million.

A midsize alternative, the Bird topped out with a respectable circulation of 25,000 and won plaudits coast to coast. In Learner’s estimation, it displayed casual sophistication in writing style and a cool graphic brilliance. In a feature on the underground press in 1971, the “60 Minutes” television show said that if the Los Angeles Free Press was The New York Times of the undergrounds, Atlanta’s Bird was its Wall Street Journal, a literate paper with an analytical bent.

But success did not come without struggle. From the beginning, the Bird faced both external and internal pressures that made its flight a dizzying one.

After a damaging local smear campaign, the paper was forced to go all the way to New Orleans to find a printer. Atlanta police seized the May 26, 1969, issue, featuring a cover cartoon of an armed man shouting an obscenity under a Coca- Cola logo. Bird hawkers were harassed by police, and the paper had to go to court to maintain use of the U.S. mail system. In 1972, the paper, which carried no insurance, was the victim of an unsolved firebombing that demolished its offices near Piedmont Park.

And if the outside world didn’t succeed in destroying the paper, it sometimes seemed its own staff might

Learner’s book used the Bird as “a particularly clear example” of internal tension between cultural and political forces, a common problem for the underground papers. And staff members acknowledge there were constant discussions to define the correct ideology at regular Monday and Thursday meetings. Committed to the notion of participatory democracy, the Bird staff was organized as a collective that made decisions by majority vote and preferably by consensus.

Picking cover art, even choosing what color ink to use, was often controversial. As the women’s movement gained strength, a women’s caucus was formed to battle staff sexism. And bitter debates developed over whether the paper, which began, according to one staffer, with roots in existentialist Christian philosophy, should adopt pure Marxist- Leninist positions.

Even amid the strife, however, Bird staffers continued to try to shape a radicalism uniquely suited to the South. “A lot of us were from the South, and we kind of thought in Southern terms,” said Steve Wise, who covered the peace movement within the military, international affairs and rock ‘n’ roll.

Wise believes the Bird contributed positively to the changes that transformed the region. ‘You can see change occurring. I grew up in a segregated society,” said Wise, a Newport News, Va., native now working as a courier while writing a thesis on Latin American history for a master’s degree from Georgia State University. “When we started, the level of racism here was a lot higher than it is now. … For basically a white paper, our pro-civil rights coverage was different from any paper around. “

Howard Romaine, another founder who is now a lawyer and. aspiring country music songwriter in Nashville, Tenn., agreed that the Bird had an impact on race relations. “I never did have any revolutionary expectations,” he said, “except for the notion that black people voting in the South was revolutionary.”

Other former staffers say the paper helped to end the Vietnam War and to create a climate that has prevented the United States from going to war in Central America. And on the local level, they say the Bird helped diminish police brutality.

But by the early 1970s, some of the original staff members already had begun to fly the coop, some to other movement jobs, a few to other alternative media, most simply to try to make ends meet as they began to raise families. (The Bird’s, salaries of $25 to $60 a week did not go far.) ,

While staff” members could be replaced and were, readers could not — once members of the movement that provided the circulation base began moving into the Me Decade, losing much of their interest in the issues covered by the paper. “After ’72, the movement just sort of collapsed,” said Wise, who will celebrate his 45th birthday at the reunion. “The anti-war movement went into a very swift eclipse when the draft ended.” In re-reading the papers lately, he said, he was interested up until 1973. Afterward, the paper just seemed to be all critique without any feeling that anything positive — action by a movement — would result, he said.

A 1984 attempt at reviving the Bird with about half new staff and half old hands fizzled. “Basically, it was sort of a nostalgic thing, and there really wasn’t a market,” said Wise, who participated partly because his fondest hope had once been that the Bird would become a permanent institution like New York’s Village Voice.

“I think it was a great tragedy what happened to the Bird,” said Romaine. To become commercially viable, however, the paper would have had to open itself up to more diverse viewpoints. And, as several staffers commented, the Bird was always short on people who knew a lot about running a successful business.

However, Saturday will not be a time for pondering what might have been but for celebrating what was. “We’ve had great times laughing and talking and remembering all our old arguments,” said Stephanie Coffin, a part-time English instructor at Georgia State University who was one of the reunion organizers. “That was a fantastic period. It was an incredibly creative, incredibly alive period. And it was totally consuming. It left a vacuum in a lot of people’s lives.”