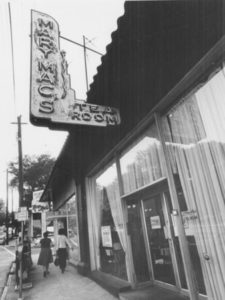

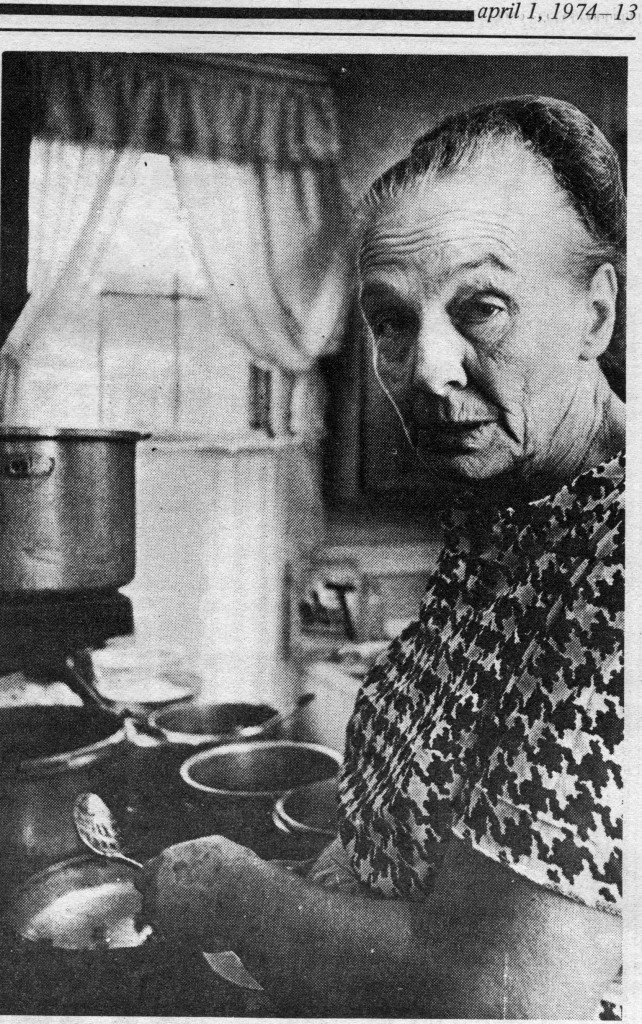

The first reason most people in Atlanta had to visit Inman Park during the 70s was to eat at Ma Hull’s Boarding House was across from where the Marta station in Inman Park is now. the building still exists, but it is not the same.

The first reason most people in Atlanta had to visit Inman Park during the 70s was to eat at Ma Hull’s Boarding House was across from where the Marta station in Inman Park is now. the building still exists, but it is not the same.

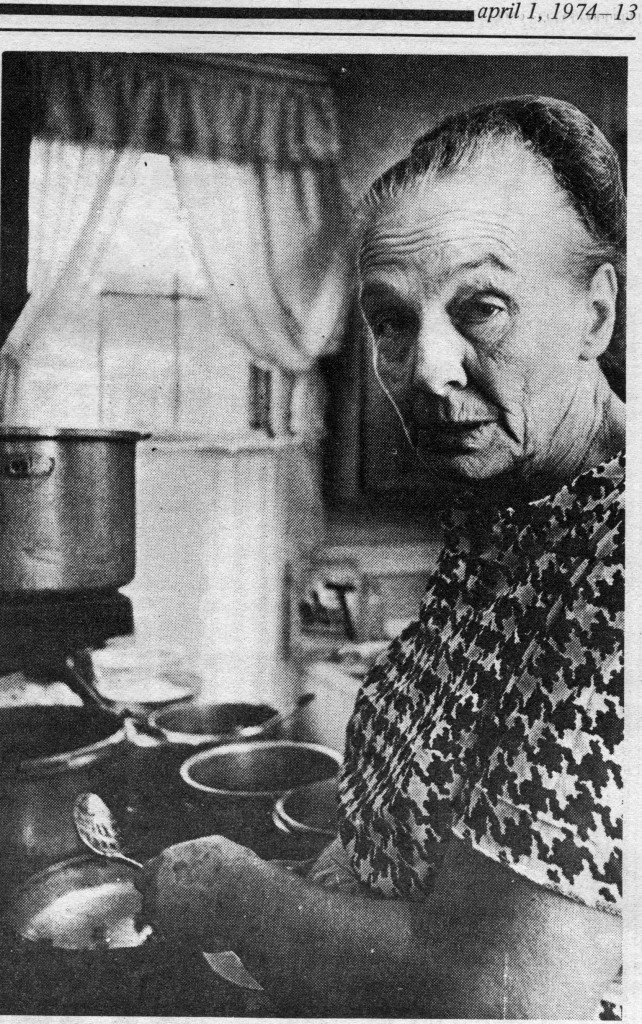

Seal Place remembers Ma Hull

The Great Speckled Bird Jan 7, 1974 Vol. 7 #1 pg. 19

The Great Speckled Bird Jan 7, 1974 Vol. 7 #1 pg. 19

A Conversation With Ma Hull

She came to Atlanta from Ashland, Alabama, with her husband Ross, back in the early years of the Depression. She raised nine children and now has “30 some-Odd” grandchildren and three great grandchildren. Over the years she lived in different sections of Atlanta and worked in factories and kitchens to eke out a living for herself and her family.

Around 1958 she began taking in boarders and six years ago moved her household to the present location at the corner of Edgewood Avenue and Hurt Street in Inman Park.

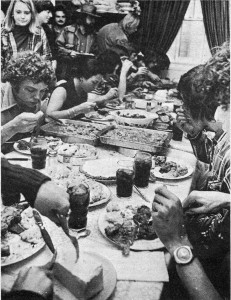

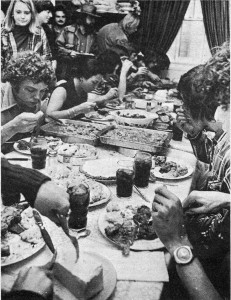

Two years ago her boarders began bringing their friends home to supper, and word-of-mouth advertising did the rest. Friends came, then friends of friends, and today Ma Hull is something of a legend as she continues to serve up an incredible variety of down home Southern cooking: ham, ribs, roast, chicken, string beans, yams, butter beans, dressing, greens, casseroles, banana pudding, cheese cake, pies, cakes, corn bread, biscuits and iced tea.

Matching the variety of food is the variety of people: working families, students, long-hairs, uniformed policemen, elderly people in the neighborhood.

Matching the variety of food is the variety of people: working families, students, long-hairs, uniformed policemen, elderly people in the neighborhood.

Participating in the following conversation with Mrs. Hull were Bill, a long-time boarder with Mrs. Hull, Kathleen, who recently began working there, and Ross Hull, her husband, who alternately sang hymns, cracked jokes, and joined in the conversation while snapping a bushel of string beans during the interview.

BIRD: I suppose you ‘re doing this as much because you like to do it as to make money.

MRS. HULL: I don’t make no money. We just have a living place to stay. As far as making our dime, we do not. We just have a shelter over our head. I cannot hold down a job with this heart trouble and sugar diabetes, ’cause it’s all I can do to breathe sometimes, just ordinary breathing. And he can’t work, so that’s it.

I just don’t know if I can keep it up much longer. Now I’m go’n tell you, I worked, all the week.

Paid the ones that helped me, paid for my groceries. I didn’t have anything left. Well, I just can’t sit here and not have a dime.

BIRD: How long have you been doing this?

MRS. HULL: I’ve been keeping boarders for 16 years—not, you know, a crowd. I’ve got three that’s just like the family. They’ve stayed with me for 16 years. And then we moved over here six year ago. Then I took in others. I’ve had six in this house, maybe seven. (It was) a pretty fair living until things went up so high.

BIRD: You’ve been serving meals all that time?

MRS. HULL: No, just about two years. I made it real well with the boarders, then I got where I didn’t have—they wasn’t any here. You say anything to ’em about drinking and they’ll leave. And I’ve done had one to put me in the hospital and cost me $3,369.

BIRD: What did he do?

MRS. HULL: Well. he caused me to have a heart attack-he was drunk-showing out. And the doctor said I just could not have no excitement. And every one of ’em knows it. So, it’s a hard ole life to go, ’cause you know this day and time there’s not many people you see that don’t drink, men and women.

I just can’t stand it. My husband was the biggest drunkard you ever seen until three year ago. And I went through a livin’ hell with it. And he froze down here in a car. His feet busted open. He ain’t had a shoe on his feet in almost three years—for liquor. I cannot stand it.

BIRD: Just seen too much of what it can do?

MRS. HULL: That’s right. It’ll tear your home up. It’ll cause you to tote cussin’s. It’ll cause you to do peculiar things you never in this world thought about. I just haven’t got any use for it.

ROSS (MR. HULL): . . . stringing beans, that’s all I do.

MRS..HULL: Well, I think when you marry you’re supposed to not be studying nobody else.

ROSS: I ain’t studying nobody.

MRS. HULL: Well you just then said you did, didn’t ya?

KATHLEEN: Are y’all fightin’ again? What’d she say?

ROSS: I’m afraid to talk now.

KATHLEEN: You’re afraid to talk?

ROSS: H’mmm.

MRS. HULL: They ain’t none of ’em in this house got me a’scared. I never seen but one man I was scared of. We lived on Washington Street. He came in and boarded one week. I made him move. He had to stoop down to get in at the door. And he had a voice, I’m go’n tell you what’s the truth, now you think I’m telling you a story, but it’d shake the floor. He didn’t talk normal like nobody, and I was natural born a-scared of him. When that week was up I said, “Find you a place to move.”

BIRD: Mrs. Hull, what do you think about all the changes going on in this neighborhood?

MRS. HULL: I think it’s nice. Now you take when we come here, like the fourth house down, it just looked like a nothing. You couldn’t walk the sidewalks or yards, and now it’s beautiful.

BIRD: They ‘re threatening to put a freeway in right over here (the 1-485 corridor is right across Hurt Street from the Hull’s house.)

MRS. HULL: Well they not go’n do it. They gettin’ along enough now. We been here six years and that’s been tore down and they ain’t done nothin’ and they not going to. 1 wish they’d put up a shopping center or something.

KATHLEEN: How come?

MRS. HULL: ‘Cause.

KATHLEEN: ‘Cause why?

MRS. HULL: Simply because!

KATHLEEN: Haven’t you heard that song about tear down the trees and build up a parking lot? That’s what you sound like.

MRS. HULL: I don’t care. I’d rather they was a shopping center over there than like it is.

BIRD: A lot of the houses in Inman Park have been sold and re-sold, and the prices are rising. How has this affected your situation here?

MRS. HULL: I’d just love to know. I guess this one’ll be sold again. In the last two years it’s been sold I don’t know how many times.

BIRD: And ya’ll have just stayed on here getting different landlords? ,

MRS. HULL: Different men to come collect the rent and different men to come collect the rent and. .. (Ross interrupts)

ROSS: And they say stay on, stay on, and I ask em if they want us to move. No, we don’t want you to move—yet.

MRS. HULL: I’d like to have it painted inside but I can’t get nobody to paint it, and I can’t do it myself.

BIRD: The landlord won’t fix it up?

MRS. HULL: Well, they’ve sold it again. Haas has it now. I believe that’s his name, but he fixed the bathroom upstairs and this little place in the kitchen. I look to get up in the morning to find my Frigidaire sittin’ down in the basement, the floor’s so bad. So you don’t know what to do.

ROSS: (singing)? What a friend we have in Jesus

MRS. HULL: Now, when I was in pretty fair health I enjoyed it (cooking meals), but now I just got to where it don’t make no difference to me if I do or if I don’t. Nothing in my house don’t mean nothing to me. It’s just that I’m sick. I can’t do what I want to do. I can’t keep my house like I want to keep it.

BILL: You can’t when you get old! You can’t stay young all your life!

MRS. HULL: I ain’t all that old! I’m just 65, that ain’t old! Lord, my Momma is 80-some-odd years old and gets about, and Ross’ Momma is 110 years old, and if she could see, she could walk all over me and stomp me!

BILL: I bet your Momma hadn’t done the work you done either.

MRS. HULL: No, Momma ain’t never had to work. I worked all my life.

My daddy had three or four families of colored people that done the work. Us girls hit it, though, now don’t you think we didn’t. There was five of us, and we went to that field from sunup to sundown.

KATHLEEN: How did you and Ross meet?

MRS. HULL: Well, he was on a saw mill camp. My dad built a… what do you call it, Ross. Those boilers?

ROSS: Dutch oven, dutch oven. Mother, dutch oven, dutch oven.

MRS. HULL: And Ross met him, he come up there buying watermelons, and my Dad went back down there and done some work, and Ross got a place and boarded up there and we run away and got married.

BIRD: You eloped!

MRS. HULL: Yeah. Whew! They said my Momma was toppin’ them trees. (Laughter)

BILL: I run away and got married, and I wish I had kepa running, too. – –

MRS. HULL: She (Mama) went off that morning, – wasn’t nobody there, Papa went somewhere. So, we left. Ross had to go back and face the battle, though. He had to carry the car back. A man and woman went with us, they said Momma was down there toppin’ them trees when dark come and I hadn’t come home. See, it just worked so good.

We stayed at his Daddy’s a week and then I went back home to get my clothes. I never will forget what my Daddy said. He said, “You played hell.”

I’ve had a rugged ole life, I’m tellin’ ya. I’ve worked like a dog. 1 raised my family here in Georgia. I had seven girls and two boys. And I’m thankful I can sit here and say that I never went to jail and got nary one of my children out of jail, and I’ve never had nary a one of ’em in trouble. And they ain’t many mothers can say that.

BIRD: Mrs. Hull, what is your first name?

MRS. HULL: Vernon.

BIRD: Vernon. Oh, Vernon is your name? I thought maybe his name was Vernon Ross or something.

MRS. HULL: No, his name’s Ross. My name is Vernon. I worked in a meat packing house one time for about six months where they cut meat, you know? Big Boss come in there one Friday giving out checks. He said, “You’re a woman drawing a man’s pay!” I said, “Well, my God, you know’d I was a woman. I wear woman’s clothes all the time!” He never said anymore. I go by the name of “Ma” everywhere I’ve ever lived. Everybody calls me “Ma.”

BIRD: Do you follow politics very much?

MRS. HULL: No, because I get too mad. They don’t do justice of it. Now Nixon’s not done right, and you know he ain’t done right. I’m 65 years old and I have never seen this country in the mess it’s in today. And they’ll—I don’t want to get started on it. That’s the one thing I don’t mess with; cause I don’t know whether I’d be votin’ for the right man or the wrong man, ’cause they’ll all promise anything ’til they get in there, and they don’t do what they say they’re going do. So I just let ’em run it and dab-it.

BIRD: What do you think about young people?

MRS. HULL: Well, I think some of ’em has lost all the morals they ever had. I may be a-saying a mouthful, I don’t know how you believe; I do not believe in men and women living together without being married. If you can’t go with one another long enough to trust one another and find out what kind of person, leave ’em alone, ’cause that is not right laying up together as man and wife.

A girl that will lay up with a man, let him use her body, she’s a-growing older every day. She gets old, who wants her? I say, be a lady, marry and get you a true husband, somebody that loves you and will take care of you in your old days. ‘Cause this here man that lays up with you, he ain’t go’n do it. He go’n walk off and leave you; he go’n get tired of you. He won’t trust you. That’s just the way I feel about When in your old days. ‘Cause this here man that lays up with you, he ain’t go’n do it. He go’n walk off and leave you’, he go’n get tired of you. He won’t trust you. That’s just the way I feel about the younger generation. I might’ve said something I oughtn’t to have said, but that’s just the way I feel. I believe, if you play around, get pregnant, I believe you raise that baby. Don’t take it out here and kill it, or give it to somebody else. You had the pleasure of gettin’ it, now you have the pleasure of raising that baby and take care of it.

ROSS: Kneel at the cross.

BIRD: Are you a member of a church?

MRS. HULL: No.

BIRD: What were you raised?

MRS. HULL: Baptist. That’s what I believe in. I’ve been saved. But I don’t live like I should. But I’m thankful for this, I can set here and look you straight in the face and tell you I’ve never been in a beer joint. I have never run around on my husband. I didn’t run around as a girl. I can say I have never did out one thing that I’m ashamed of: When 1 get mad I say bad words, which that’s wrong. But I tell ya, some of these people right here will make you say it. Now they’ll make you say it.

BIRD: You ‘ve been in and out of the hospital a lot lately?

MRS. HULL: Yes. I’ve had four heart attacks and two blockages in the last two years. Now for the last two weeks, I can’t even stoop over to get a bread pan. I can’t do nothing. I don’t hurt, but there’s no strength, and just all I can do to breathe. And the doctor said my heart was tilted down and said the load I was trying to carry was too much for my heart.

I know I ain’t got but a short time here, and I want to go to a better place. Each day I get worse and worse.

I know my Dad went in just in the shape I’m in. They found him out in the chicken pen dead. And they go’n find me in the bed dead, ’cause they’s times I can’t hardly get off the bed to breathe. 1 know from the last two weeks I can’t last much longer, ’cause I just can’t make it, that’s all there is to it. And when that water comes up in my lungs, if I wasn’t close where I could go to the hospital, I couldn’t stand it.

BIRD: Well, you ‘ye touched an awful lot of people in the two years you ‘ve been doing this work.

MRS. HULL: Yeah, I have lots of friends. I’m really thankful for that, I have got lots of friends.

ROSS: If you could get it through her thick head to go to that doctor, he could help her some. Now I don’t say he could cure her, but he could help her. But she won’t do that. I’ve begged that women, and I’ve begged her, and the young’uns have too, and she won’t do it. She’s so hard-headed she will not do it.

MRS. HULL: Well, I’ll go when I know I have to.

ROSS: That’s where you’re wrong. If you’d go before you had to, ( it wouldn’t be so bad).

MRS. HULL: Well, why don’t you take some of the same advice. I’ll tell you right now, it’s not fun to go down to that hospital. And this doctor and that doctor and this doctor—you don’t know who to listen at and who not. And I don’t have the money to get another doctor.

I’ll tell you what, when I was in Georgia Baptist, Doctor Taylor said to me not to turn my hand to do nuthin’. But, I have it to do. He sent the welfare out here. She said she would give me .$38 a month. Well, you know I can’t do nothin’ with $38. If I’d leave Ross, they’d give me $80. What can I do with $80?

Grady has been good to me. When I go down there, they’re good to me. I’d just rather be at home, and if I got to die, I’d rather die at home. I know I have and I want to cook ’til I do so that my children can’t say, “Well I had to take care of my mother.” I don’t want ’em to have it to say.

I enjoy cooking if I’ve got something to cook with, and I’ll do the best I can as long as 1 can.

I enjoy cooking if I’ve got something to cook with, and I’ll do the best I can as long as I can. When I’m through, then I’ve fought the battle to the end.

Mrs. Hull’s failing health has caused her to quit serving lunches, but she is still serving supper at 6 pm Monday through Friday for $2.50 and Sunday dinner for $3.00 at 12:30.