The Great Speckled Bird Oct 19, 1970 vol3 #47 pg. 12-13

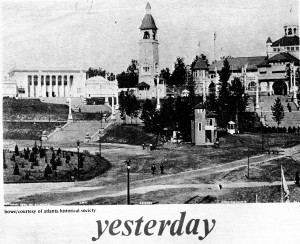

The Piedmont Park of today began with the “Cotton States International Exposition of 1895.” The land, purchased from the Gentlemen’s (now Piedmont) Driving Club, was first used for a local event. “The Piedmont Exposition” in 1887 prepared the way for what became a world’s fair of its day.

The Piedmont Park of today began with the “Cotton States International Exposition of 1895.” The land, purchased from the Gentlemen’s (now Piedmont) Driving Club, was first used for a local event. “The Piedmont Exposition” in 1887 prepared the way for what became a world’s fair of its day.

The Exposition was a project of the South’s young white men-on-the-go who were working to industrialize the South in the North’s image. Many of today’s native white Atlantans look back nostalgically on the Exposition as an example of how Atlanta used to be able to get things done even in the most difficult times.

Atlanta and the South did overcome the effects construction with some bootstrap-tugging and a lot of help from Northern capitalists, particularly the railroad interests. The removal of the remaining Northern troops from the South in 1877 had sealed the fate of the newly “emancipated” blacks. The Exposition announces to the world that the South had made it. The Exposition was basically a trade fair ushering in heavy Northern capital like the textile industry, which for years would exploit Southern workers.

But not everything had been smoothed out by 1895. The Exposition needed financial support. To hold the Exposition it was essential that the U.S. Government make an investment. To convince a still northern Republican Congress to appropriate $200,000 for the Exposition and a Government Building, a committee of Blacks was formed and plans for a Negro Building were made. Congress was not hard to convince by that time and the money was appropriated..

So on opening day, in the auditorium at the top of the steps leading down to the Grand Plaza (now the athletic field), Booker T. Washington made his “Five Fingers” address, arguing that blacks and whites should remain socially as separate as the fingers on a hand, laying the basis for his later differences with a militant professor at Atlanta University, W.E.B. DuBois. The Exposition’s report describes how “a veritable era of good feeling between the white and black was ushered in by the Exposition.”It didn’t work out that way. Jim Crow laws were instituted throughout the South during this period, and Atlanta had “race riots” in the early 1900’s.

The Exposition was a grand affair. Gondolas and “electric launches” plied the waters of the lake. John Philip Sousa’s band played every day in the auditorium. The Liberty Bed was brought down from Philadelphia and placed on exhibit. In the Midway the first motion picture theater in this country did business as “living pictures” and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show performed in the southeast corner of the park.

The Exposition defined the park to come. The contours of today’s park were shaped by the chain gangs that labored for months preparing for Expo-95. The Grand Plaza became the athletic field, the foundation of the Manufactures Building became the tennis courts. Midway Heights and the Wild West area became the golf course, and the central terrace became the steps by the pavilion.

The City purchased the grounds in 1904 over the objections of some who argued that it was too far from town. By extending the city boundaries in the same year, the city fathers effectively silenced those opponents. During the years 1909-1910 the Exposition grounds were converted into the park, which today remains pretty much the same as it was then.

Now the Atlanta Parks Department has developed a master plan for the renovation of she park in keeping with its “Atlanta Parks and Recreation Plan-Projection 1983” recommendations.

The staff of the parks department has good intentions. Trouble is that Atlanta over the years has fallen far behind national park standards. Based on minimal standards, Atlanta has less than half the park acreage it needs. Over the past few years the Parks Department has been shaping up. A greenhouse complex was built in Piedmont Park, an arborist came on staff, the staff worked hard.

Then came Ivan Allen’s dream-The Atlanta Stadium. To obtain financing for the project the City agreed to guarantee the stadium bonds. The money to guarantee the bonds was taken from the Parks Improvement Fund. One half the fund-about $480,000 has been taken every year except fiscal 1969 and the chances are that it will continue to be lost to the Parks Department.

Jack Delius. General Manager of Parks, has appealed to the Aldermanic Ordinance and Legislation Committee to request that the State Legislature increase Parks Improvement Fund, but so far nothing done. So the Parks department dues the best it can with limited resources to implement its vision of 1983.

So that means that the Piedmont Park Master Plan does not really fall in line with its 1983 projections. The report describes Piedmont Park as the only park in the city which “offers a large land area for unstructured leisure time use.” The report recognizes that one of the more common uses of a park is “simply the pleasure of getting away from traffic, buildings and others characteristics to enjoy strolling along wooded walks among trees and in fields or rowing a boat across a pond.” In fact the plan calls for the creation of four other large parks in the city to provide open space for “unstructured leisure time.”

But if the City’s Master Plan is put into effect as it stands, most of Piedmont Park’s usable “leisure time” space will be destroyed. The plan will create a central zone full of structures, parking lots, and program activities, areas bounded on the south by a pretty golf course, inaccessible to all but a few golfers, and a beautiful forest to the north, untouched by the plan but still used by a relatively few persons.

Two of the main features of the plan should be implemented immediately. The Parks Department would like to close the park to cars and provide inexpensive bicycle rental to those who prefer wheels to foot. Boat rental is planned on the lakes, which are eventually to be connected with a bridge.

Two of the main features of the plan should be implemented immediately. The Parks Department would like to close the park to cars and provide inexpensive bicycle rental to those who prefer wheels to foot. Boat rental is planned on the lakes, which are eventually to be connected with a bridge.

The problem is that the plan calls for lots of parking when the streets are closed. Land adjacent to the park is regarded as too expensive; another idea, to build underground parking under the tennis courts was rejected for the same reason. So parking is planned for the eastern and northern shores of the swimming lake, the area between the Legion Post and the 14th Street Gate, and the area around the greenhouses. That’s a hell of a lot of the park’s best “leisure time” space.

Is it wise to plan extensive parking in a central park along major traffic arteries in a city which must develop effective mass transportation? Is parking needed when office parking lots along nearby Peachtree Street stand empty over the weekends? What’s the sense of closing the park streets to cars if they are going to be sitting on parking lots inside the park?

The free and open athletic field will be lost in the plan. A new $387,000 softball tournament facility was to have been built this year in the southern end of the field. The city has an extensive softball program which serves many people. More lighted diamonds are needed. But tournament facilities are used for tournaments only one week out of the year and the complex will fence in over half of the athletic field. Perhaps the softball teams could get by with lights on all the diamonds and portable grandstands which would allow for other uses than just softball? Maybe the softball complex is one thing which could easily be located on other city property? In fact, the Atlanta Civic Design Commission, an advisory group, has come out against the complex, suggesting that it might be located at Lakewood Park. Apparently work on the complex (if it stays in the park) would probably not begin until next winter.

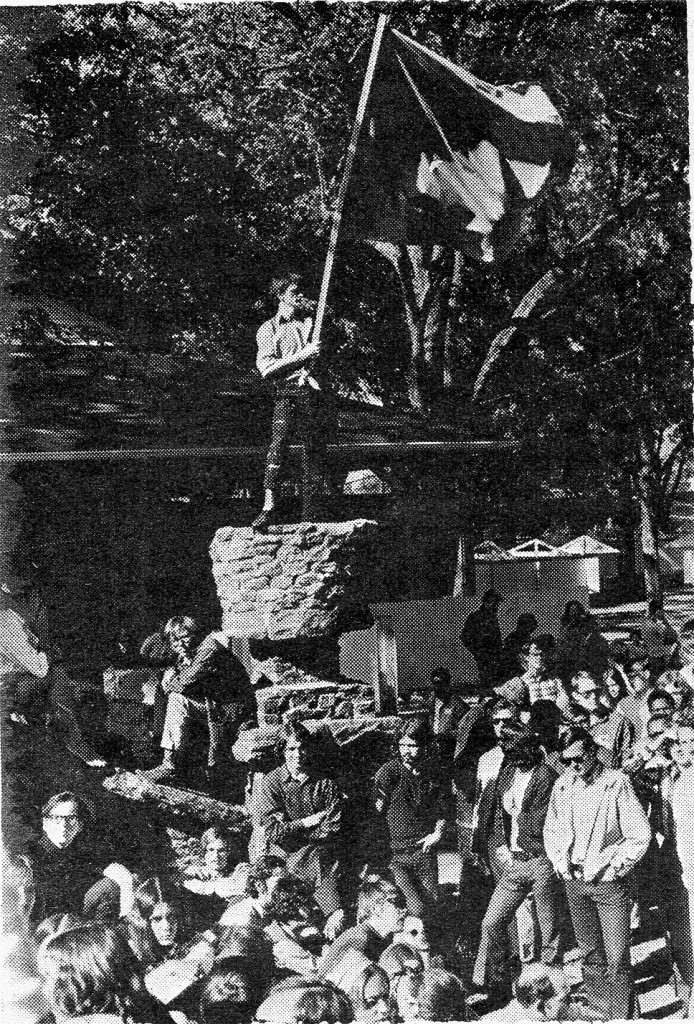

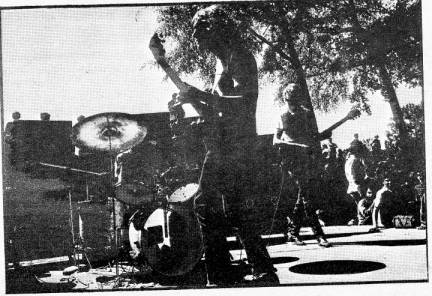

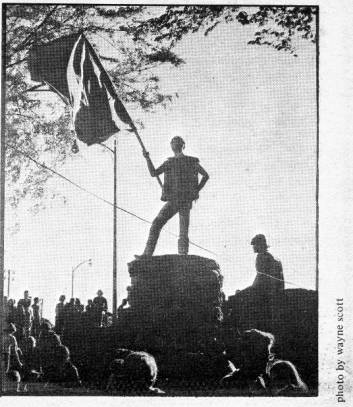

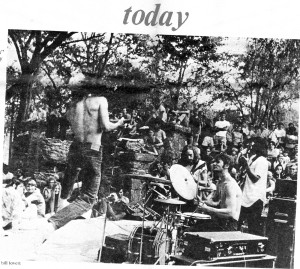

Also on the athletic field is to be a large swimming pool facility to replace the swimming lake. The Health Department says that the present facilities do not meet its requirements because there is no continuous filtration or automatic chlorination. The combination of the pool and softball facilities will mean little or no space for kite flying, informal sports, or music concerts.

To replace the present swimming facilities a waterside concert area is planned with a shell stage out over the water and seating for 1500—2000 where the present concession building stands. A smaller amphitheater is projected for the west end of the fishing lake near the 12th Street entrance.

A restaurant and sidewalk cafe will be located along the north shore of the fishing lake. If they were reasonably priced that might not be too bad, except that very nice free space is destroyed. Then at the 14th Street entrance a gym and recreation center will be built. Both should be established in this community, both are needed-but perhaps not in the park.

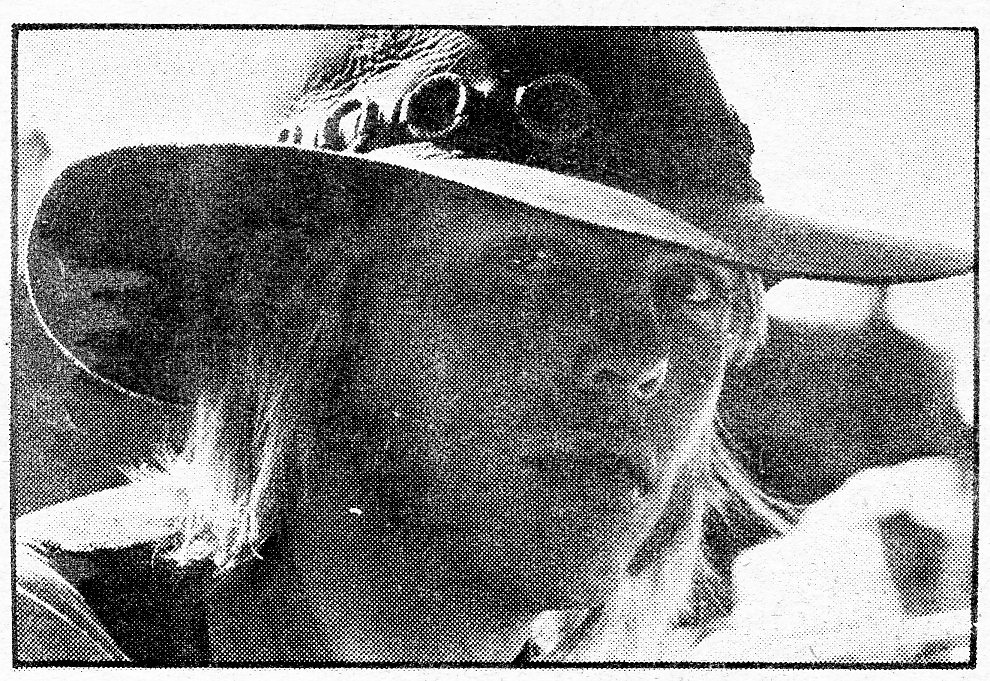

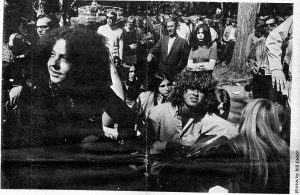

The master plan is preliminary, subject to change. But three projects—softball complex, gym, and pool have been approved by the Aldermanic Parks Committee, although only funds for the softball complex have been allocated. No community or public hearings have been held on either the master plan or the three approved projects. According to Delius, hearings of some sort are planned this winter. The Bird will keep you informed of developments in the Park. When hearings are held we’ll let you know so you can attend. If they are not held we’ll let you know so you can raise hell. The park should not be lost to this community. It’s too important.

—gene guerrero